By Barbara van Koppen,

Scientist Emerita at the International Water Management Institute

The earlier RWSN webinars and blogs about pastoralists’ water governance highlight how these communities have found solutions for survival and wellbeing in fragile environments, based on in-depth ecological knowledge . The blogs also expose the risks and threats when external agencies, such as government, NGOs, and private sector intervene, even with the best intentions of providing support. It underlines, again, the vital importance for external agencies to listen to everybody, leaving no one behind, from the very first phases of planning action.

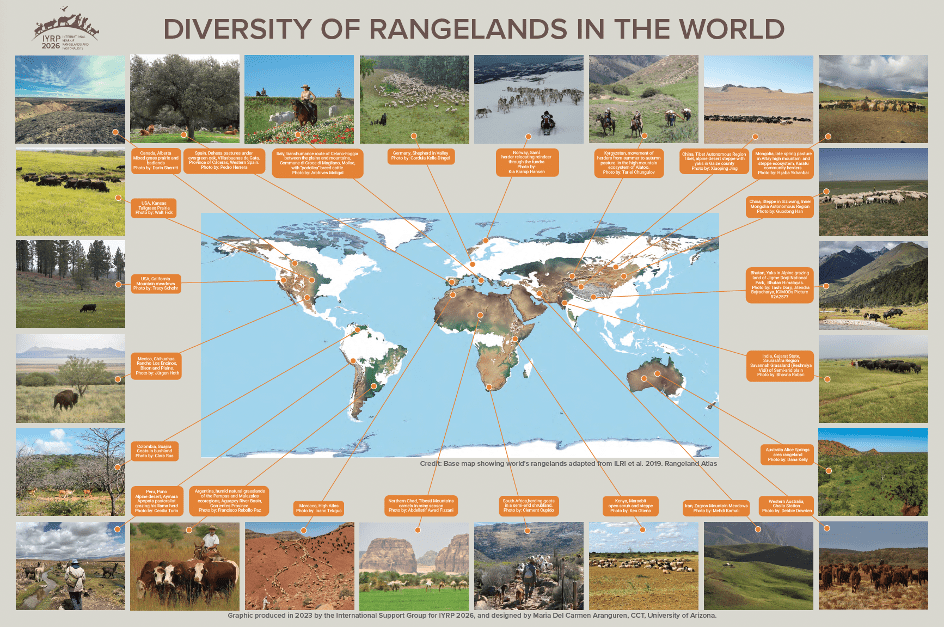

This blog, by Barbara van Koppen explores whether and how these insights can apply more widely. Do the various ways in which pastoralists generate solutions and receive external support or face threats also apply to smallholders and mixed farmers as well as fisherfolks in low-income rural areas in general? When we read ‘pastoralist’, can we interpret this more generally as ‘marginalized rural water user’, or in many cases even ‘humankind’? If such overlap exist, would more cross-fertilisation strengthen general calls for community-led planning and for a recognition of customary water tenure in policy and law? Let us explore, starting with pastoralists’ integrated water management.

Multiple uses

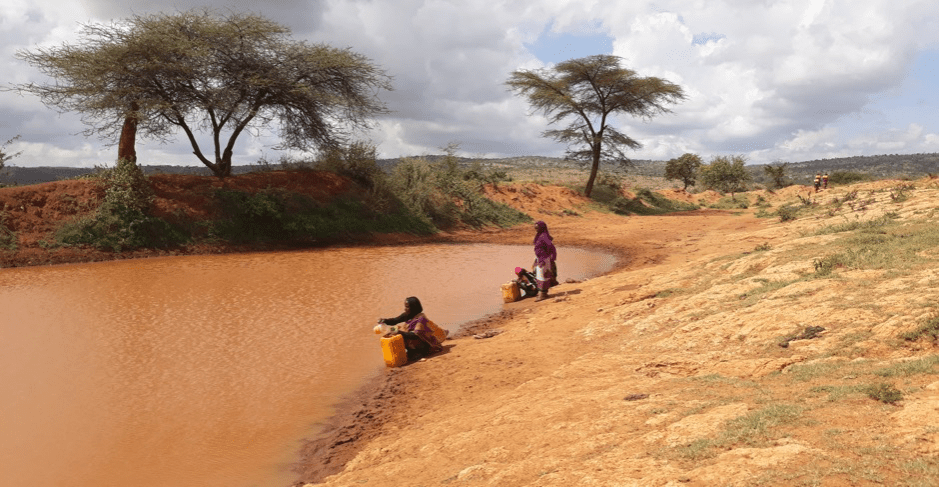

For pastoralists, water is life in many ways. Humans and animals need water daily and year-round for drinking. Every human also daily depends on water for domestic uses. Further, seasonal or year-round water enables vegetation growth for immediate use or storage for human livelihoods: nature’s grass, shrubs, and trees, or cultivated animal feed, or crops or fruits for own consumption or sale. Water is also needed for other livelihood activities, for example, the trade of milk. For humans, silos don’t exist; one use cannot without the other. When access to water is limited and prioritization inevitable, during seasonal droughts, pastoralists set a lower priority on their own drinking and other domestic uses above absolute minimum quantities than drinking by their animals. Together, the multiple water uses bring health and wealth and vice-versa.

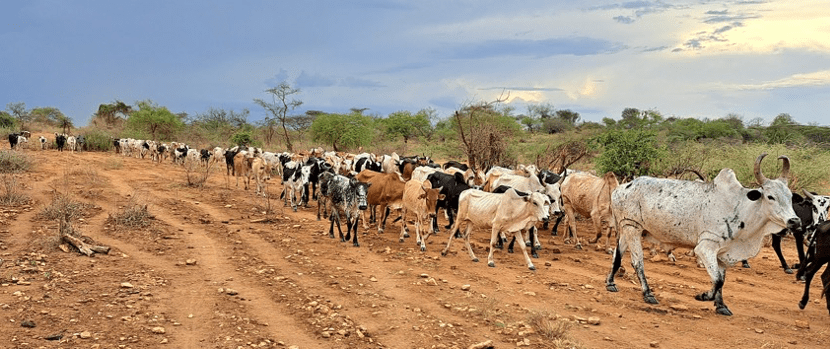

Moving to nature’s multiple, variable, unpredictable water sources

This life dependency on variable, only partly predictable and land-bound water resources, underpins age-old knowledge of the local integrated hydrological cycle of multiple sources: precipitation, surface water bodies, run-off, soil moisture (green water), wetlands, and groundwater. Without Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) to combine multiple sources, survival is impossible. This shapes pastoralists’ mobility to the sites of their seasonal and year-round uses: in dry seasons the (usually male) herders move their cattle to grazing areas and permanent water sources, for example up in the mountains. Even homes can remain mobile. Depending on seasons, part of mixed farming communities, may move their herds out and live in temporary houses.

Making water move to sites of use: soil and water conservation and multi-purpose infrastructure

Pastoralists also make water move to, or stay in the favourite sites of use for themselves and their animals. Soil and water conservation in the rainy season feeds grasses, shrubs and trees for grazing or improves the cultivation of feed and crops. Construction, operation and maintenance of storage and conveyance infrastructure bring water seasonally or year-round to homesteads, distant grazing or cropping areas or other preferred sites. Dug ponds, tanks and drums store water. Groundwater is storage that is recharged. Buckets to lift or carry water, wheel burrows, canals, pipes, and trucks transport water.

The (usually male) individuals or self-organized groups who invest in the infrastructure typically have the strongest claims to the water stored and conveyed for their multiple needs, but other people and animals may be attracted. Access rights are even more open for infrastructure installed by government or NGOs.

In sum, at community-level, pastoralists combine multiple local surface and groundwater sources, with various infrastructures to access water for multiple uses at multiple sites Sharing of water that flows over or under these lands shapes internal and external relationships. As the Boran say: “Water is either a source that you ‘share in’ as a member of a descent-based collectivity, or one that you ‘share out’ to signify respect” (Dahl and Megerssa 1990*). These insights and arrangements are mainly orally shared, also through culture and rituals.

All the above – multiple uses, sources, infrastructures and sharing – may sound complex, but communities can draw a map (on the ground or on paper) of this core of their livelihoods and culture in a few hours.

However, the most severe threats to pastoralists’ access to water are in the ‘sharing out’ of water with foreign and national powerful third parties, grabbing land and water and polluting for profit- and export-oriented large-scale cereal farms, plantations, mining, or tourists and game parks.

Implications for support agencies

What do you think? Don’t these features fit more settled rural communities as well? And fishers? They fit FAO’s general definition of water tenure: “Relations, customarily or formally/legally defined, between people, as individuals or groups, with regard to water” (FAO 2020**). In FAO’s Global Water Tenure Dialogue, pastoralism is a clear example of a broader growing recognition of customary, or community-based, or indigenous, water tenure.

Joining forces, the following two implications for governments and other external agencies seem equally important for pastoralists and more settled rural communities or fisherfolks.

First, any external support for improved water management should start with the above-mentioned diagnostic of a resource map. Different parts of the community (men, women, young, old, different livelihood strategies) will indicate their current situation. On this basis they will identify their problems and envision and prioritise actions, while cost-effectively indicating required support.

This diagnostic resource mapping is the moment to ensure everyone’s voices are heard, so that those who need most can prioritise action. External agencies’ mandates of support on offer should be transparent and as open as possible. Too restrictive mandates can fail to align with local priorities or ignore pastoralists and fisherfolks altogether. This may even be the case in broad approaches such as the food-energy-water nexus (which tend to ignore domestic water uses) and humanitarian aid (which may ignore animals’ and other productive needs). When broader needs than the support on offer emerge, other expertise and funding sources need to be mobilised.

Second, when water is scarce during dry seasons and droughts, prioritization is inevitable. The following prioritisation proposed by the UN Special Rapporteur on the human right to water*** provides excellent guidance for decolonized prioritisation that may well align with communities’ own prioritisation.

- 1. Water for life (domestic uses, productive uses, aquatic life);

- 2. Water for general interest;

- 3. Water for economic uses and profit making.

References

*Dahl, G.; Megerssa, G. 1990. The sources of life: Boran conceptions of wells and water. In: Palsson, G. (ed.) From water to world-making. African models and arid lands. Uppsala, Sweden: The Scandinavia Institute of African Studies. pp.21–38.

**FAO. 2020. Unpacking water tenure for improved food security and sustainable development. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 40p. (Land and Water Discussion Paper 15). https://doi.org/10.4060/cb1230en

***UN (United Nations) 2024. Water and economy nexus: managing water for productive uses from a human rights perspective. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation Pedro Arrojo Agudo. Fifty-seventh session 9 September–9 October 2024. Agenda item 3. Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development. A/HRC/57/48. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/thematic-reports/ahrc5748-water-andeconomy-nexus-managing-water-productive-uses-human