It was 21 years ago that I was first confronted with manual drilling. I had just started my PhD research at Cranfield University. The idea was to develop a human operated rig that could break through harder (laterite) formation, test it in an African country, and have it adopted by the private sector… in three years. Back then I could never have imagined that in 2019 (and in my mid-40’s), that I would join ten others for a seminar hosted in Madrid, Spain on the role of manual drilling to reach universal water access.

Looking back, the goals of the project were unrealistic, but we did not know that at the time, and research provides space for considerable learning. Oh, and by the way, digital cameras were very new on the market in 1998. My colleague had one, which produced recognisable, but quite grainy images.

The UK Department for International Development (DFID) Knowledge and Research (KAR) funded research project, “Low Cost Drilling” took me to Uganda, and three years of field work in collaboration with the (now) Ministry of Water and Environment and district local governments in Mukono and Mpigi. Following initial trials in a field in the UK, UNICEF and the government enabled use of the rig to provide drinking water supplies within their joint drinking water programme (called WES).

We proved that the new technology (which we called the Pounder Rig) could work, but embedding it in Uganda proved to be beyond us within the three-year period. In the meantime, I had gone from standing in a hotel lobby to make calls to landlines and leaving messages for people who were not there, to having my first mobile phone. My photographs remained analogue; a digital camera being well out of financial reach at the time.

The PhD research process taught me so much, but let me try to stay close to the topic of manual drilling. The subject of innovation diffusion was opened up, and I came to learn that the successful adoption of any technology is brought about by much more than technical aspects (my PhD thesis provides insights into this in case you wish to be one of the very few people to read it).

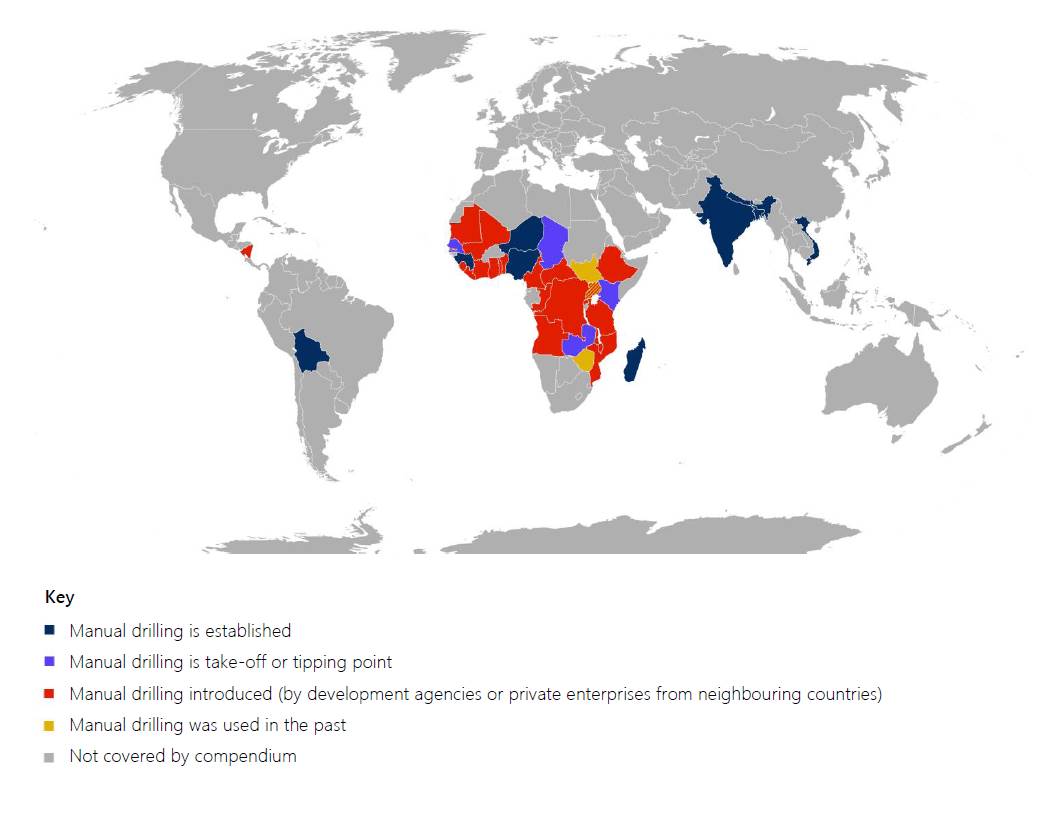

Over the subsequent years, I was extremely fortunate to have the chance to keep on returning to the subject of manual drilling. The collaboration with UNICEF to follow-up their efforts to support manual drilling professionalization in several countries was a welcome opportunity, leading to not only the 2015 manual drilling compendium, but also more in-depth documentation of the status quo in Nigeria and Chad. In short, we documented that by 2015 manual drilling technologies had provided drinking water sources in at least 36 countries.

There are quite a few organisations introducing manual drilling technology, including private enterprises developing new markets; local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with overseas funding; governments relying on foreign/local expertise as well as foreign companies and NGOs (including several faith-based organisations).

However, as I started to learn while in Uganda some 20 years ago, the diffusion of innovation has different phases. Broadly speaking, there is the introduction phase, the uptake phase (also known as the valley of death, given that many technologies are not taken up), and the established phase. Mobile phones combined with digital cameras (aka SMART phones), that can enable you to make calls and take high resolution photographs are in the established phase.

Dr Pedro Martinez-Santos, the new UNESCO Chair in “Appropriate Technologies for Human Development” at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid chose the role of manual drilling technologies towards universal water access as the topic for the first seminar of the chair in April 2019. I was privileged to be among the eleven people who attended the event. I thus had the opportunity to listen to, and learn from professionals talking of specific experiences in Nigeria, Senegal, the Demographic of Congo, Zambia and Guinea Bissau as well as more widely. It was also a chance to present my own experiences and reflections, and engage in open and fee dialogue.

Returning, after two decades, to an academic environment and reflecting on a topic that has engaged me ever since, is something that may only happen once in a lifetime! There is much that I could say about manual drilling, and even more to learn about, but I close this blog with three short messages:

- Manual drilling is fully established in some countries and less so in others. Globally, a suite of technologies, when used in the right locations and with professional construction methods, can provide drinking water of good quality. Manual drilling undoubtedly has a significant role to play in reaching the Sustainable Development Goal Targets for Drinking Water, especially in remote areas, but also in rapidly growing urban centres where piped supplies are failing to provide reliable services.

- Manual drilling is not just about technology but also: the businesses that invest; the drillers (male and female) that need be able to work professionally; the data that can be collected; and the question of whether some people are left behind while others tap the water from their back yards. And there is the regulation (alongside other innovations) needed ensure that the sources are, and remain safe to drink, tapping sustainable groundwater resources.

- I close by urging not only governments, but also development partners to consider manual drilling, and manual drillers in policies, legislation, investments and capacity strengthening efforts rather than leaving it on the margins. As we experienced in Madrid in April, engage in real dialogue and listening with the different actors involved. The rewards may even be beyond your expectations!

You can download all the presentations from the Madrid seminar from here.

RWSN has collated information on manual drilling technologies and associated wider issues here.

Course modules

Course modules