Il s’agit du second d’une série de quatre blogs intitulée ‘Le forage professionnel de puits d’eau: Apprendre de l’Ouganda” de Elisabeth Liddle et d’un webinaire en 2019 sur le forage de puits professionnel. Cette série s’appuie sur les recherches menées en Ouganda par Liddle et Fenner (2018). Nous vous invitons à nous faire part de vos commentaires en réponse à ce blog ci-dessous. [Note : Le blog original a été révisé le 3 avril 2019 pour corriger une représentation inexacte de la situation].

Si l’accès à des sources d’eau améliorées a augmenté de manière progressive dans l’ensemble de l’Afrique subsaharienne rurale, plusieurs études ont soulevé des problèmes concernant la capacité de ces sources à fournir des quantités d’eau sûres et adéquates à long terme (Foster et al., 2018 ; Kebede et al., 2017 ; Owor et al., 2017 ; Adank et al., 2014). La conception et l’emplacement des forages sont essentiels à ce que le point d’eau continue à fournir des quantités d’eau sûres et adéquates. L’accès à des informations détaillées et précises sur les eaux souterraines peut grandement faciliter le choix du site et la conception des forages (UNICEF/Skat, 2016 ; Carter et al., 2014).

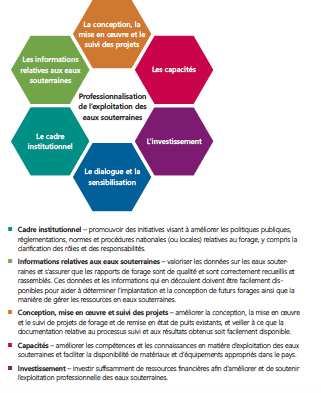

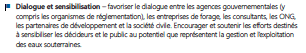

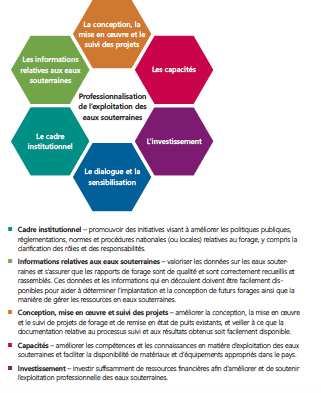

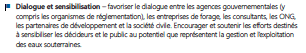

La Fondation Skat et l’UNICEF ont été les principaux défenseurs d’un accès plus répandu à des données détaillées sur les eaux souterraines, y compris la récente note d’orientation qui souligne que “l’information sur les eaux souterraines” est essentielle à l’amélioration de la qualité de la mise en œuvre des forages dans les pays à revenus faible et intermédiaire (voir Figure 1 ; UNICEF/Skat, 2016). Dans ce blog, je donne un aperçu de la manière dont l’Ouganda a cherché à améliorer l’accès aux données sur les eaux souterraines ces dernières années.

Fig. 1: Six domaines d’engagement pour l’exploitation professionnelle des eaux souterraines (Skat/ UNICEF, 2018)

La cartographie des ressources en eaux souterraines en Ouganda

Des mesures importantes ont été prises ces dernières années pour améliorer l’accès aux données détaillées sur les eaux souterraines en Ouganda. La plupart de ces activités ont débuté en 2000 lorsque la Direction de la gestion des ressources en eau du Ministère de l’eau et de l’environnement a lancé un projet de cartographie des eaux souterraines à l’échelle nationale. À l’aide de données tirées des rapports d’achèvement des forages que les entrepreneurs de forage doivent soumettre chaque trimestre, la Direction de la gestion des ressources en eau a élaboré une série de cartes pour chaque district. Il s’agit notamment des cartes suivantes :

- Carte de localisation des sources d’eau, avec carte géologique à l’appui.

- Carte des technologies recommandées par source d’eau (la recommandation de la technologie se base sur la profondeur de l’impact de l’aquifère principal et les données sur le rendement).

- Carte des conditions hydrogéologiques – elle comprend 4 sous-cartes : Profondeur présumée du premier impact avec l’eau[1], la profondeur présumée de l’impact avec l’aquifère principal[2], l’épaisseur présumée des morts-terrains[3], etla profondeur statique présumée du niveau d’eau[4].

- Carte de la qualité des eaux souterraines : celle-ci met en évidence les zones où la qualité de l’eau pourrait poser problème.

- Potentiel des eaux souterraines – Carte du taux de réussite du forage : combine le taux de réussite prévu du rendement [5] et les conditions prévues de la qualité de l’eau.

Tindimugaya (2004) donne plus de détails sur ces cartes, ainsi que les façons dont elles peuvent faciliter le processus de mise en œuvre. Un exemple de cartes pour le district de Kibaale est disponible sur le site Web du Ministère de l’Eau et de l’Environnement.

Ce travail de cartographie est en cours, cependant, en mai 2017, la Direction de la gestion des ressources en eau avait cartographié 85% des districts de l’Ouganda. L’ampleur de ces cartes et le niveau de détail qu’elles contiennent sont remarquables. Ces cartes ont rendu service aux collectivités locales de district, aux organisations non gouvernementales et autres responsables de l’implantation et de la construction des points d’eau.

Des défis persistents

Bien que l’Ouganda ait fait des progrès remarquables au cours des dernières années grâce à ses efforts de cartographie des eaux souterraines, plusieurs défis persistent (Liddle et Fenner, 2018), liés pour la plupart à l’exactitude des données. Lors d’entretiens avec les personnes interrogées en Ouganda dans le cadre de nos recherches, on nous a signalé que dans certains cas (mais pas tous), des données inexactes ont été fournies. Lorsqu’on examine les raisons pour lesquelles des données inexactes sont parfois fournies aux autorités, deux poins clés ont été relevés :

- Souvent, il n’y a pas de consultant qualifié sur place à temps plein pour la supervision du forage. Bien qu’il incombe à l’entrepreneur de forage de faire consigner le journal de forage par un membre du personnel, un superviseur indépendant devrait également tenir un journal et vérifier l’exactitude du journal du foreur avant de le soumettre à la Direction de la gestion des ressources en eau. Cependant, sans supervision à temps plein, cela n’est pas possible. De plus, même avec une supervision à temps plein, si le superviseur n’est pas un hydrogéologue, il est peu probable qu’il tiendra des registres précis et détaillés.

- Les conditions de paiement forfaitaires “pas d’eau, pas de paiement”, selon lesquelles les foreurs ougandais sont souvent payés (voir le blog “Contrats clés en main pour l’implantation et le forage des puits d’eau“). Ces modalités de paiement exigent des foreurs qu’ils prouvent qu’ils aient foré avec succès un point d’eau pour être payés; par conséquent, certains foreurs auraient exagéré le rendement d’un forage donné afin d’être payés. Les données faussées ainsi obtenues sont préoccupantes, car non seulement ces forages auront du mal à fournir des quantités adéquates d’eau après construction, mais les données liées à leur haut rendement sont ensuite saisies dans la base de données des journaux de forage et utilisées pour produire les cartes hydrogéologiques. Il est essentiel d’améliorer la qualité de la supervision des forages et de veiller à ce que les données ne soient pas faussées de cette façon si l’on veut que les cartes de la Direction de la gestion des ressources en eau soient plus précises à l’avenir.

Dans l’ensemble, l’Ouganda a fait des progrès remarquables au cours des deux dernières décennies en augmentant le niveau d’information sur les eaux souterraines disponible dans le pays. Il y a très peu d’exemples sur le continent africain comparables à ce que l’Ouganda a accompli ! Comme indiqué plus haut, les cartes qui en résultent représentent un grand avantage pour les autorités locales de district, les organisations non gouvernementales et les autres responsables de l’implantation et de la construction des points d’eau.

Il est essentiel pour l’Ouganda d’améliorer la précision des rapports d’achèvement des forages. En outre, d’autres pays pourront prendre conscience de ces défis lorsqu’ils entreprennent leurs propres exercices de cartographie et veiller à ce que les mesures nécessaires soient en place pour prévenir ces problèmes dans leur contexte.

Qu’en pensez-vous?

Alors, qu’en pensez-vous? Avez-vous de l’expérience en matière de collecte ou gestion de données sur les eaux souterraines? Cela devrait-il être entrepris dans votre pays? Vous pouvez répondre ci-dessous en postant un commentaire, ou vous pouvez participer au webinaire en direct le 14 mai (inscriptions ici)

[1] Profondeur présumée du premier impact avec l’eau : la profondeur à laquelle un foreur est susceptible de rencontrer des eaux souterraines pour la première fois. Dans la plupart des cas, le foreur devra poursuivre le forage au-delà de ce point pour que le trou de forage puisse fournir suffisamment d’eau aux utilisateurs.

[2] Profondeur présumée de l’impact avec l’aquifère principal : la profondeur à laquelle un foreur est susceptible de trouver l’aquifère principal qui sera en mesure de fournir des quantités suffisantes d’eau aux utilisateuCarte de la qualité des eaux souterraines : celle-ci met en évidence les zones où la qualité de l’eau pourrait poser problème.

[3] Les morts-terrains désignent les matériaux non consolidés qui recouvrent le substratum rocheux. La carte de l’épaisseur prévue des morts-terrains met en évidence la profondeur prévue des matériaux non consolidé dans l’ensemble de l’Ouganda.

[4] Profondeur statique présumée du niveau d’eau = la profondeur d’eau souterraine attendue sans perturbation de pompage.

[5] Le ” taux de réussite du rendement ” fait référence à un forage capable de supporter un débit de pompage de 500 litres/heure. Si un forage peut maintenir ce taux de pompage, il est considéré comme une réussite en ce qui concerne le rendement.

Références

Adank, M., Kumasi, T.C., Chimbar, T.L., Atengdem, J., Agbemor, B.D., Dickinson, N., and Abbey, E. (2014). The state of handpump water services in Ghana: Findings from three districts, 37th WEDC International Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014, Available from https://wedc-knowledge.lboro.ac.uk/resources/conference/37/Adank-1976.pdf

Carter, R., Chilton, J., Danert, K. & Olschewski, A. (2014) Siting of Drilled Water Wells – A Guide for Project Managers. RWSN Publication 2014-11 , RWSN , St Gallen, Switzerland, Available from http://www.rural-water-supply.net/en/resources/details/187

Foster, T., Willetts, J., Lane, M. Thomson, P. Katuva, J., and Hope, R. (2018). Risk factors associated with rural water supply failure: A 30-year retrospective study of handpumps on the south coast of Kenya. Science of the Total Environment,, 626, 156-164, Available from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969717337324

Kebede, S., MacDonald, A.M., Bonsor, H.C, Dessie, N., Yehualaeshet, T., Wolde, G., Wilson, P., Whaley, L., and Lark, R.M. (2017). UPGro Hidden Crisis Research Consortium: unravelling past failures for future success in Rural Water Supply. Survey 1 Results, Country Report Ethiopia. Nottingham, UK: BGS (OR/17/024), Available from https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/516998/

Liddle, E.S. and Fenner, R.A. (2018). Review of handpump-borehole implementation in Uganda. Nottingham, UK: BGS (OR/18/002), Available from https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/520591/

Owor, M., MacDonald, A.M., Bonsor, H.C., Okullo, J., Katusiime, F., Alupo, G., Berochan, G., Tumusiime, C., Lapworth, D., Whaley, L., and Lark, R.M. (2017). UPGro Hidden Crisis Research Consortium. Survey 1 Country Report, Uganda. Nottingham, UK: BGS (OR/17/029), Available from https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/518403/

Tindimugaya, C. (2004). Groundwater mapping and its implications for rural water supply coverage in Uganda. 30th WEDC International Conference, Vientiane, Lao PDR, 2004. Available from https://wedc-knowledge.lboro.ac.uk/resources/conference/30/Tindimugaya.pdf

UNICEF/Skat (2016). Professional water well drilling: A UNICEF guidance note. St Gallen, Switzerland: Skat and UNICEF. Available from http://www.rural-water-supply.net/en/resources/details/775

Remerciements

Ce travail fait partie du projet Hidden Crisis du programme de recherche UPGro – cofinancé par le NERC, le DFID et l’ESRC.

Le travail de terrain entrepris pour ce rapport fait partie de la recherche doctorale des auteurs à l’Université de Cambridge, sous la supervision du Professeur Richard Fenner. Ce travail sur le terrain a été financé par le Ryoichi Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship Fund et UPGro : Hidden Crisis.

Merci à ceux d’entre vous de l’Université de Makerere et de WaterAid Ouganda qui m’ont apporté un soutien logistique, y compris sur le terrain, pendant que je menais les entretiens pour ce rapport (en particulier le Dr Michael Owor, Felece Katusiime et Joseph Okullo de l’Université Makerere et Gloria Berochan de WaterAid Uganda). Merci également à tous les répondants d’avoir été enthousiastes et disposés à participer à cette recherche.

Photo: “Carte des technologies recommandées par source d’eau souterraine dans la division Eau du bureau du district de Kayunga” (Source: Elisabeth Liddle).