Stop the Rot during ZAWAFE 2023 Zambia – 4/4

This blog is part of a four-part series covering the presentations given at the 11th Zambia Water Forum and Exhibition. The event, themed “Accelerating Water Security and Sanitation Investments in Zambia: Towards Agenda 2023 through the Zambia Water Investment Programme”, lasted three days.

Our blog series takes a focused look at the presentations and discussions that revolved around “Addressing Rapid Hand Pump Corrosion in Zambia – Stop the Rot!”, which was co-convened by UNICEF and WaterAid, together with Ask for Water GmbH and the RWSN, hosted by Skat Foundation.

Cover photo: Red, iron-rich water being pumped. Photo: WaterAid Uganda

Second session:

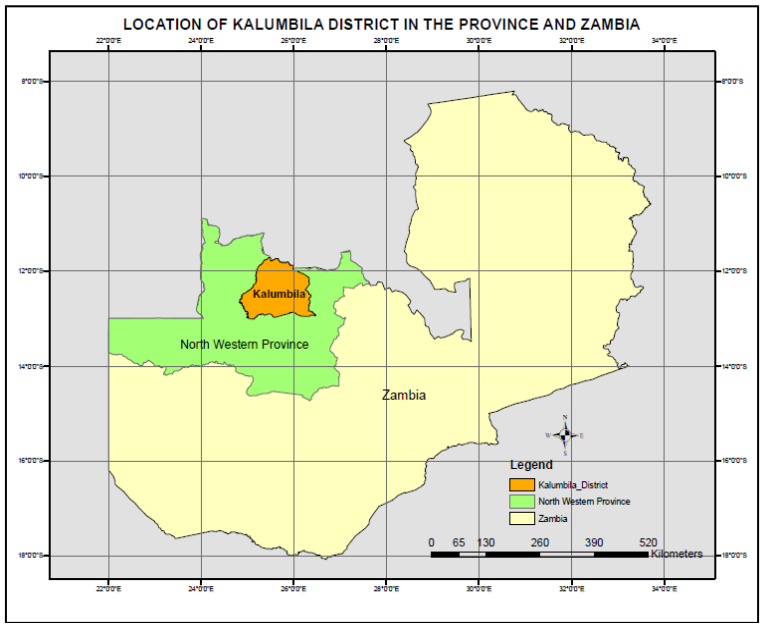

The role of galvanized pipes in the corrosion and failure of hand pumps

Empowered Communities Helping Others (ECHO) has been implementing a safe water project since 2020. This is a Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) project, whose main intervention is borehole rehabilitation which is implemented in rural parts of Zambia’s Western and Central Provinces, in collaboration with the Local Authority. In practice, the need to rehabilitate a borehole arises when a functioning borehole presents usage problems such as non-production of water, worn out parts such as pipes, rods, handles, chains, cylinders, water chambers, pedestal, head assembly, bearings, etc.

Since 2020, ECHO has rehabilitated a total of about 850 boreholes in Central and Western Zambia, benefiting a total of about 255,000 people.

It was found that rehabilitating a borehole can be more economical than constructing a new one. It is simpler and faster and can be an appropriate solution in an emergency because it doesn’t require things like mobilizing a drilling rig. However, if the rehabilitated borehole is to be used for a long time, it is important to estimate its life expectancy.

The rehabilitation option chosen depends on the conditions of the existing borehole, the causes of the damage, the technical and logistic options, and the existing alternatives such as the construction of a new water point.

According to the severity of the borehole problems, the work requirements may vary from a simple repair at the surface to re-equipment.

For the project, all GI pipes are replaced with new PVC ones. This is done in order to prevent and reduce iron contamination (as a result of corrosion) which from the past four years we have observed is a contributing factor to borehole failure and abandonment

The main observed sources of iron are:

▪ From natural sources in the aquifer

▪ From pump components such as steel casings and galvanized pipes.

▪ In other instances, a combination of both has been observed to be possible. ▪ Within 3 to 6 months of installing hand pumps with galvanized material, pipes and rods have been found to be heavily corroded.

▪ When corrosion is the main source of iron, iron concentrations reduce drastically when water is pumped out and fresh recharge is allowed. If iron concentrations remain high throughout during continued pumping, the case has been that it is likely the iron is coming from the aquifer.

Experiences on hand pump corrosion

Hand pumps with GI pipes, sometimes only a year or two old have corroded, and people have returned to unprotected water sources. Water with pH below 6 has been observed to have corroded pipes. High iron concentrations in handpumps have been a usual occurrence this has been observed through regular water quality testing and evaluating the change in iron concentration over the period of our operations. Stainless steel pipes and rods had corrosion rates lower than galvanized iron (GI) pipes and rods.

Experiences on hand pump corrosion

The brown or reddish color is observed in the morning when the pumps had not been used during the night

However, groundwater has been observed to hold significant concentrations of iron but appears clear and colorless. When this water is pumped out after being exposed to the atmosphere, the color changes to red/brown.

Figure 3: Sampled on Friday 2nd June 2023 in Central Province.

General complaints recorded from communities:

Within weeks and months of installation, communities would begin to complain about water quality. These complaints range from metallic taste, odor, and the appearance of water. Also, the communities would report discoloration of water and cloths and highly turbid water.

All these result in people abandoning the water point and going back to unprotected alternative water sources.

Positive observations

The use of uPVC pipes and stainless-steel adapters has so far shown positive results in reducing iron contamination. After switching from galvanized pipes to UPVC, the communities have observed reduced to no brown or reddish color in the water. uPVC pipes last long, so you won’t have to worry about replacing them anytime soon. Since uPVC is non-porous, uPVC pipes help by preventing any contamination from occurring. uPVC is resistant to corrosion as it is not susceptible to chemical and electrochemical reactions, so there are better option in controlling iron contamination. The use of uPVC pipes and stainless-steel adapters has so far shown positive results in reducing iron contamination

Figure 4: Riser pipe removal and water quality testing for an installation that was less than six months old by ECHO.

What we are advocating for:

▪ Stakeholders should address the handpumps with corrosion problems as a priority in order to guarantee the water quality we supply to the people.

▪ Testing boreholes that present iron contamination to determine whether the source of iron is from the aquifer or from corrosion. This will provide the best options for the right material to equip the water point with

▪ Competent borehole drilling and rehabilitation supervision should be ensured so that all standards and specifications are adhered to.

▪ Regular water quality analysis is undertaken, and critical parameters are tested to address problems such as corrosion and other related problems that shorten the life span of a hand pump

You are invited to access the presentations HERE, along with the session’s concept and report. If you would like to dive deeper into the enriching exploration of water challenges and solutions through the Stop the Rot initiative, visit this page.

About the author:

Annie Kalusa – Kapambwe presenting at at ZAWAFE 2023

Annie Kalusa is an accomplished development practitioner and administrator. Currently working for a local Zambian NGO Empowered Communities Helping Others (ECHO) in Zambia, focusing on improving the wellbeing of Vulnerable Rural Communities. Her areas of focus are climate resilient Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH). She is currently developing her thesis on Rural Agriculture Practices and Mechanisms for Water Resource Management.

Photo credits: Annie Kalusa