Bono and Ahafo Region, Ghana — Ensuring the safety and quality of drinking water supplies is a pressing concern for public health. While urban areas often benefit from established procedures for water quality monitoring, rural regions frequently lack resources and expertise. This article, produced by USAID’s REAL-Water Activity, explores how a rural water innovation is shifting the communal mindset from “water is life” to “safe water is life,” emphasizing the importance of water quality and the heightened expectations for water operators. It also highlights the unique challenge that researchers face in meeting the growing demand for solutions, which often outpaces the rate at which they are able to complete their evaluations. The article elaborates on this “researcher’s dilemma” and its implications.

Category: REAL-Water

“Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings” Innovation 7: Blended Public/Private Finance.

Image Credit: Report World Bank, 2014. ©Albert Gonzalez Farran/UNAMID

This blog post is part of a series that summarizes the REAL-Water report, “Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings,” which was developed by The Aquaya Institute and REAL-Water consortium members with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The report specifically focuses on identifying innovative financing mechanisms to tackle the significant challenge of providing safe and sustainable water supply in low-resource rural communities. These communities are characterized by smaller populations, dispersed settlements, and economic disadvantages, which create obstacles for cost recovery and hinder the realization of economies of scale.

Financial innovations have emerged as viable solutions to improve access to water supply services in low-resource settings. The REAL-Water report identifies seven financing or funding concepts that have the potential to address water supply challenges in rural communities:

- Village Savings for Water

- Digital Financial Services

- Water Quality Assurance Funds

- Performance-Based Funding

- Development Impact Bonds

- Standardized Life-Cycle Costing

- Blending Public/Private Finance

Understanding Blended Public/Private Finance.

Water supply development in low- and middle-income countries has traditionally relied on public or aid funding, rather than commercial financing. “Blended” finance refers to leveraging public funds (e.g., concessional loans or grants from national governments or development banks) to mobilize additional capital from private banks or investment groups (OECD 2019b).

Combining development finance with private investment can assume different structures to reduce risk, employing a range of instruments (e.g., equity, debt, partnerships, technical assistance, grant-funded transaction design, guarantees, or insurance; Figure 1; OECD 2019a; Convergence 2023). The most common blended finance instruments across the development sector from 2018–2019 were direct investments in companies or subsidiaries, loan guarantees, “syndicated” loans, and lines of credit (OECD 2019a). Syndicated loans come from a group of collaborating financial institutions (a loan syndicate) to a single borrower, reducing the risk and buy-in amount needed for each individual group and/or ensuring sufficient specialized expertise. Alternatively, a smaller amount of pure grant funding may be used to support technical assistance or subsidies, with the goal of attracting other investors.

Figure 1. The four most common blended finance structures (adapted from Convergence 2023)

Examples

Although not all water-related “public-private partnerships” leverage public funding to attract commercial finance, these long-term collaborative arrangements among one or more government and private sector entities have been in place for decades in low- and middle-income countries, including throughout Africa, with encouraging results. Overall,

private operators have tended to be more efficient than governments at managing construction, service delivery, and asset maintenance (World Bank Group 2014). One frequently documented benefit among several Sub-Saharan African examples, where private management covers an estimated one-third of small piped water schemes, has been reduction of “non-revenue” water, or water losses for which production costs are never recovered. Among small-scale water providers in Uganda, a private sector participation model led to expanded coverage and financial performance with only modest tariff increases (World Bank Group 2014; Hirn 2013). Active connections tripled over 10 years with tariffs rising less than inflation.

In Madagascar, a host of rural community water user committees and private water operators have signed long-term concession agreements in which a private company invests in the water system to increase household access, generate more revenue, and share profits. This model has been replicated over roughly 15 years with donor support, such as USAID’s Rural Access to New Opportunities in Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (RANO WASH) activity (Tetra Tech 2021).

Another long-running example of blended finance comes from Benin. Between 2007 and 2017, more than half of Benin’s rural piped water systems transitioned to private operation and maintenance contracts known as “affermages” (Comair, Delfieux, and Dakoure Sou 2021; Migan and Trémolet Consulting 2015). In these agreements, a private operator collects tariffs and then retains a percentage of an agreed-upon price per unit of water sold, turning over the remainder to the contracting authority (Janssens 2011). The initial pilot with 10 private operators successfully rehabilitated all water systems with no additional costs to the customers (World Bank Group 2018); however, subsequent scale-up experience brought a pivot to regional contracts to attract more professional operators. In 2022, a 10-year public-private partnership was formed with a consortium of French companies (Eranove, UDUMA, and Vergnet Hydro) to rehabilitate, extend, and operate rural water systems for 100% customer coverage (Marteau 2022). Public funds will ensure private connections and tariffs remain affordable.

Although some examples (e.g., Madagascar, Benin, Cambodia) have applied blended finance to rural water supply in low- and middle-income countries, it remains at a proof-of-concept stage. Blended finance is possible where rural water provision is more organized and mature and where people pay consistently, justifying lending. This is more likely to be the case in middle-income economies.

Further proof-of-concept is required to evaluate blended financing to drive rural water supply performance. It faces a dual challenge: persuading commercial lenders that water supply represents a lucrative investment opportunity and persuading water service providers to seek loans at rates higher than those routinely offered by development finance institutions.

Blended finance projects create an evidence base for effective public investment and in turn, incentivize the capture of better financial and impact data (Convergence 2019). Objective selection criteria may help “prime” service providers to continue the behaviors and actions that support blended finance (USAID 2022). Building the foundations for blended finance will require a transition period with accompanying public sector support, to allow for a paradigm shift on the part of both borrowers (who face increased pressure to manage operations efficiently) and lenders (who often do not know the market well enough to participate in investment opportunities).

While they take time, these adjustments have taken place in other sectors, most notably energy (IRC n.d.). Pories, Fonseca, and Delmon (2019) detail foundational issues ranging from governmental sector planning and tariff setting to service provider project preparation and financial market distortions. Experiences with the approach will elucidate the degree to which blended finance can work at large scales, but transformation is unlikely to occur rapidly.

Do you want to know more? Access to the complete report on financial innovations for rural water supply in low-resource settings HERE.

The information provided on this website is not official U.S. government information and does not represent the views or positions of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the U.S. Government.

References:

- Comair, Georges, Charles Delfieux, and Yeli Mariam Dakoure Sou. 2021. “Ambitious Reforms and Private-Sector Engagement Improve Access to Water in Benin.” World Bank Blogs (blog). 2021. https://blogs.worldbank.org/water/ambitious-reforms-and-private-sector-engagement-improve-access-water-benin.

- Convergence. 2019. “Blended Finance for Water & Sanitation.” Data Brief. Convergence.

- Convergence. 2023. “Blended Finance.” 2023.

- Hirn, Maximilian. 2013. “Private Sector Participation in the Ugandan Water Sector:A Review of 10 Years of Private Management of Small Town Water Systems.” Working Paper. Nairobi, Kenya: Water and Sanitation Program (WSP).

- Janssens, Jan. 2011. “The Affermage-Lease Contract in Water Supply and Sanitation.” An explanatory note on issues relevant to public-private partnerships. PPP Insights. Washington, DC: The World Bank (PPPIRC).

- Marteau, M. 2022. “Benin: Eranove, UDUMA and Vergnet Hydro Are Set to Deliver a Continuous Drinking Water Service to 9.3 Million Beninese by 2030.” UDUMA (blog). 2022.

- Migan, Sylvain Adokpo and Trémolet Consulting. 2015. “Benin – Innovative Public Private-Partnerships for Rural Water Services Sustainability – A Case Study.” World Bank WSP and the International Finance Corporation.

- OECD 2019a. “Amounts Mobilised from the Private Sector for Development.” 2019.

- OECD. 2019b. “Making Blended Finance Work for Water and Sanitation: Unlocking Commercial Finance for SDG 6.” Policy Highlights. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://doi.org/10.1787/5efc8950-en.

- Pories, Lesley, Catarina Fonseca, and Victoria Delmon. 2019. “Mobilising Finance for WASH: Getting the Foundations Right.” Water 11

- Tetra Tech. 2021. “Mid-Term Performance Evaluation of Madagascar Rural Access to New Opportunities in Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (RANO WASH) Activity.” Final Report. Mid-Term Performance Evaluation of RANO WASH. USAID.

- USAID. 2022. “Accessing Commercial Finance for Water and Sanitation Service Providers in Kenya, Cambodia, and Senegal.” USAID’s Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Finance (WASH-FIN) Project.

- World Bank Group. 2014. “Water PPPs in Africa.” World Bank Group and World Bank Water and Sanitation Program.

“Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings”Innovation 6: Standardized life-cycle costing.

Image credit: © 2011 IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre. Enumerator from WASHCost Mozambique team collects costs data from community. (taken by Jeske Verhoeven)

This blog post is part of a series that summarizes the REAL-Water report, “Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings,” which was developed by The Aquaya Institute and REAL-Water consortium members with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The report specifically focuses on identifying innovative financing mechanisms to tackle the significant challenge of providing safe and sustainable water supply in low-resource rural communities. These communities are characterized by smaller populations, dispersed settlements, and economic disadvantages, which create obstacles for cost recovery and hinder the realization of economies of scale.

Financial innovations have emerged as viable solutions to improve access to water supply services in low-resource settings. The REAL-Water report identifies seven financing or funding concepts that have the potential to address water supply challenges in rural communities:

- Village Savings for Water

- Digital Financial Services

- Water Quality Assurance Funds

- Performance-Based Funding

- Development Impact Bonds

- Standardized Life-Cycle Costing

- Blending Public/Private Finance

Understanding standardized life-cycle costing

One tool of asset management, life-cycle costing, has been used for many years to account for all costs of a product, system, or program from its inception to disposal (Sherif and Kolarik 1981). “Life-cycle” costs represent the aggregate financial expense of ensuring delivery of adequate, equitable, and sustainable water services to a specified population (Fonseca et al. 2010). Beyond calculations, the approach seeks to mainstream life-cycle considerations into institutional processes. It covers all expenditures, such as hardware, software, operation, maintenance, source water protection, training and planning support, replacement costs, and shifts needed to meet water demand. To accurately assess financing needs, service providers should categorize different types of expenses and quantify the total requirement, as well as when costs and revenues accrue.

In low-income rural areas, standardizing approaches to life-cycle costing could help to clarify how much and what type of funding might be needed to sustain water supply operations. The WASHCost project from 2008–2013 (Fonseca et al. 2011; 2010) and the State of the Safe Water Enterprises Market study (Dalberg 2017) found that carefully quantifying and ensuring funding for full life-cycle costs (particularly capital maintenance expenditures) is critical to maintaining sustainability. A common framework and step-by-step approach were proposed to quantify and categorize life-cycle costs (Table 1).

Examples

IRC developed and piloted a rural water life-cycle costing approach under the WASHCost project (Veenkant and Fonseca 2019; Table 1), which aimed to capture the full costs of providing adequate services (rather than just the initial cost of infrastructure). The approach can be used to assess water services in rural communities as well as refugee and emergency settlements. Cost categories include construction, implementation, maintenance, and replacement.

The Rural Water Supply Network (RWSN) Directory applies the same life-cycle costing approach to profile a number of rural water service providers, such as 4Ward Development (formerly called Access Development) in Ghana; AguaClara in Honduras, Nicaragua, and India; and the BESIK Programme in Timor-Leste (Deal, Furey, and Naughton 2021). It encourages further discussion on financial analyses that would inform decision-making for public services investment.

An application of the life-cycle costing approach to 14 privately run water schemes in Vietnam highlighted its ability to discern long-term profitability of rural piped water systems, particularly with respect to asset depreciation and capital maintenance (Grant et al. 2020). The analysis pointed to options for improving the schemes’ viability, such as subsidy and tariff adjustments. Another study in rural Andhra Pradesh, India, used life-cycle cost analysis to illustrate how gaps in upfront public investments in 43 villages led to service slippage due to poor operation and maintenance as well as water quality and source sustainability (Reddy et al. 2012). Infrastructure costs were overrepresented at project outset, and actual unit costs were found to be substantially higher than the official norms. In two districts of Amhara, Ethiopia, a 10-year study found that emergency water trucking and treatment costs greatly exceeded pre-planned costs of providing piped water, highlighting the importance of considering climate resilience (Godfrey and Hailemichael 2017).

Marketability

Life-cycle costing is widely used in high-income countries, where staff capacity and data tracking capabilities support completing this exercise on a regular basis. While life-cycle costing studies have been done in low- and middle-income countries, structural gaps in the water supply market prevent the practice from proliferating. More incentives are needed for implementers to track data and align on financial and operational metrics. Monitoring and evaluation web platforms like the Rural Water and Sanitation Information System (SIASAR Global)—now used in 14 countries—could be leveraged to track geocoded asset inventory and financial health (Smets and Serrano 2019).

Do you want to know more? Access to the complete report on financial innovations for rural water supply in low-resource settings HERE.

The information provided on this website is not official U.S. government information and does not represent the views or positions of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the U.S. Government.

References:

- Dalberg. 2017. “The Untapped Potential of Decentralized Solutions to Provide Safe, Sustainable Drinking Water at Large Scale: The State of the Safe Water Enterprises Market.”

- Deal, Philip, Sean Furey, and Meleesa Naughton. 2021. “The RWSN Directory of Rural Water Supply Services, Tariffs Management Models and Lifecycle Costs.” RWSN.

- Fonseca, Catarina, Richard Franceys, Charles Batchelor, Peter McIntyre, Amah Klutse, Kristin Komives, Patrick Moriarty, et al. 2010. “WASHCost Briefing Note 1: Life-Cycle Costs Approach – Glossary and Cost Components.” Brief Note 1. The Hague, The Netherlands: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre.

- Godfrey, S., and G. Hailemichael. 2017. “Life Cycle Cost Analysis of Water Supply Infrastructure Affected by Low Rainfall in Ethiopia.” Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 7 (4): 601–10.

- Grant, Melita, Tim Foster, Dao Van Dinh, Juliet Willetts, and Georgia Davis. 2020. “Life-Cycle Costs Approach for Private Piped Water Service Delivery: A Study in Rural Viet Nam.” Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 10 (4): 659–69. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2020.037.

- Reddy, V., N. Jayakumar, M. Venkataswamy, M. Snehalatha, and Charles Batchelor. 2012. “Life-Cycle Costs Approach (LCCA) for Sustainable Water Service Delivery: A Study in Rural Andhra Pradesh, India.” Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 2 (4): 279–90. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2012.062.

- Sherif, Yosef S, and William J Kolarik. 1981. “Life Cycle Costing: Concept and Practice.” Omega 9 (3): 287–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-0483(81)90035-9.

- Smets, Susanna, and Antonio Rodríguez Serrano. 2019. “From Colombia to Kyrgyz Republic and Uganda: How We Help Countries Adopt State-of-the Art Information Systems for Better Management of Rural Water Services.” The Water Blog (blog). 2019.

- Veenkant, Mathijs, and Catarina Fonseca. 2019. “Collecting Life-Cycle Cost Data for Wash Services: A Guide for Practitioners.” Working Paper. Draft. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: IRC.

“Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings”Innovation 5: Development Impact Bonds

This blog post is part of a series that summarizes the REAL-Water report, “Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings,” which was developed by The Aquaya Institute and REAL-Water consortium members with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The report specifically focuses on identifying innovative financing mechanisms to tackle the significant challenge of providing safe and sustainable water supply in low-resource rural communities. These communities are characterized by smaller populations, dispersed settlements, and economic disadvantages, which create obstacles for cost recovery and hinder the realization of economies of scale.

Financial innovations have emerged as viable solutions to improve access to water supply services in low-resource settings. The REAL-Water report identifies seven financing or funding concepts that have the potential to address water supply challenges in rural communities:

- Village Savings for Water

- Digital Financial Services

- Water Quality Assurance Funds

- Performance-Based Funding

- Development Impact Bonds

- Standardized Life-Cycle Costing

- Blending Public/Private Finance

Understanding Development Impact Bonds

One type of performance-based funding is a development impact bond (DIB), which involves involve a tripartite contract between a service provider, an impact/angel investor (seeking both financial and societal returns), and an outcome sponsor such as a development finance institution or government (Clarke, Chalkidou, and Nemzoff 2019). Moreover, DIB moves some risks from service providers and primary donors to a third-party investor, while rewarding water development outcomes.

For rural water particularly, bond investors would finance a program aimed at achieving a particular outcome or set of outcomes (e.g., extending household water connections), while service providers (e.g., public utility, private company, nongovernmental organization, or partnership) would be responsible for delivery. If and when the outcomes are verified by a third party, then the outcomes funder (e.g., government agency) should repay the social investor. In general, more successful programs give higher returns to investors.

The rationale for involving the impact investor as an intermediary is to plan the arrangement and provide the service provider with the capital required to execute planned activities (Center for Global Development and Social Finance Ltd 2013). DIBs enable development finance to retain a results-based structure without placing all of the risk on service providers themselves; rather, some risk is shifted to the impact investor (USAID and Palladium 2018). Minimizing overall risk requires careful program design, detailed costing of capital requirements and intended outcomes, and selection of a proficient service provider with a good track record of results.

Figure 1: Structure of development impact bond (Source: USAID and Palladium, 2018)

Examples

As of 2018, seven DIBs have focused on improving agricultural, education, employment, and health outcomes for people and communities, with nearly $55 million set aside for project outcome payments. If outcome targets are achieved, private investors receive all of their upfront investment back; if the service provider achieves outcomes above prespecified target levels, investors receive interest (up to 7–15%); or, they may lose money if outcomes are not achieved. DIB case studies confirm design challenges (Belt, Kuleshov, and Minneboo 2017; Oroxom 2018; Convergence, Palladum, and Bartha Centre 2018; Kitzmuller et al. 2018). In particular, managing stakeholders’ different perspectives and priorities on funding and contract structures has proven difficult (Clarke, Chalkidou, and Nemzoff 2019).

A pioneering sanitation DIB used in Cambodia offers lessons on the benefits and challenges specific to WASH services (iDE 2022).

As shown in Figure 11, the institutions involved include:

1. USAID as the outcome funder;

2. The Stone Family Foundation as the impact investor; and

3. iDE as the service provider (an international nongovernmental organization that has operated in Cambodia for many years, facilitating uptake of sanitation services in rural areas).

Figure 2: Cambodia sanitation development impact bond structure (Adapted from iDE 2022)

The Cambodian DIB launched in 2019 and will run through 2023, with a maximum of $9.99 million in outcome-based payments from USAID back to the Stone Family Foundation (iDE 2022). The DIB aims to improve rural community sanitation services, especially for the poor and hard-to-reach groups (e.g., women, children, people with disabilities, and older people) across six provinces in Cambodia. Specifically, villages must achieve open-defecation-free status, as a

means of reducing disease burdens and preventing drinking water contamination. Outcome payments can be claimed in tranches (every 6 months) dependent on local village government reports collated and submitted by iDE. To mitigate risks, the financing structure relies on a

detailed operational model embedding the cost of services (plus risk premiums). This exercise envelops not just “core” activities but also a number of “soft” (i.e., enabling or supporting) activities. Activities in the latter category include capacity building, communications, engagement

with local authorities, and sourcing materials.

After the first 18 months, the program had enabled 750 villages (out of the targeted 1,600) to be declared free of open defecation (Morse 2021). From the service provider’s perspective (iDE), the DIB provides implementation flexibility and removes some of the project governance, design, and management burden, thus conserving costs. This flexibility is particularly important given the focus on harder-to-reach villages, which benefit from testing and innovative approaches that can be fine-tuned as the program rolls out.

Scale of dissemination

No DIBs have yet been trialed for rural water services in low- and middle-income countries. Given varied values and structural limitations of water development finance institutions, they may not hold universal appeal. One (in progress) seeks to address sanitation in Cambodia.

To access further information on financial innovations for rural water supply in low-resource settings, you can download the complete report HERE.

The information provided on this website is not official U.S. government information and does not represent the views or positions of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the U.S. Government.

References:

- Belt, John, Andrey Kuleshov, and Eline Minneboo. 2017. “Development Impact Bonds: Learning from the Asháninka Cocoa and Coffee Case in Peru.” Enterprise Development and Microfinance 28 (1–2): 130–44. https://doi.org/10.3362/1755-1986.16-00029

- Center for Global Development and Social Finance Ltd. 2013. “Investing in Social Outcomes: Development Impact Bonds.” 497568.

- Clarke, Lorcan, Kalipso Chalkidou, and Cassandra Nemzoff. 2019. “Development Impact Bonds Targeting Health Outcomes,” 36.

- Convergence, Palladum, and Bartha Centre. 2018. “The Utkrisht Impact Bond: Design Grant Case Study.”

- iDE. 2022. “Press Release: World’s First $10 Million Sanitation….” Text/html. IDE. iDE. Https://www.ideglobal.org/. April 25, 2022.

- Kitzmuller, Lucas, Jeffery McManus, Neil Buddy Shah, and Kate Sturla. 2018. “Educate Girls Development Impact Bond.” Final Evaluation Report. https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/resources/educate-girls-final-report/.

- Morse, Maggie. 2021. “The Impact of an Impact Bond: Improving Health and Sanitation in Cambodia.” Darden Ideas to Action (blog). 2021.

- Oroxom, Roxanne. 2018. “Structuring and Funding Development Impact Bonds for Health: Nine Lessons from Cameroon and Beyond.” Policy Paper.

- USAID and Palladium. 2018. “Pay for Results in Development.” February 2, 2018.

“Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings” Innovation 4: Performance-based Funding

This blog post is part of a series that summarizes the REAL-Water report, “Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings,” which was developed by The Aquaya Institute and REAL-Water consortium members with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The report specifically focuses on identifying innovative financing mechanisms to tackle the significant challenge of providing safe and sustainable water supply in low-resource rural communities. These communities are characterized by smaller populations, dispersed settlements, and economic disadvantages, which create obstacles for cost recovery and hinder the realization of economies of scale.

Financial innovations have emerged as viable solutions to improve access to water supply services in low-resource settings. The REAL-Water report identifies seven financing or funding concepts that have the potential to address water supply challenges in rural communities:

- Village Savings for Water

- Digital Financial Services

- Water Quality Assurance Funds

- Performance-Based Funding

- Development Impact Bonds

- Standardized Life-Cycle Costing

- Blending Public/Private Finance

Understanding Performance-based Funding

Many water supply development projects fail due to well-meaning but poorly-executed investments (McNicholl et al. 2019). Repayable water supply investments often risk losses, due to the pervasive challenges of serving low- and middle-income rural settings. Development aid recipients, including governments and water service providers, may face challenges such as limited capacity, oversight, victims of corrupt schemes, or weak governance. These factors can affect the incentives to achieve optimal outcomes. From the funder’s perspective, poor outcomes reinforce high-risk perceptions and may steer resources away from water supply investments. The potential beneficiaries, rural water consumers, suffer the consequences with little opportunity for recourse. As a way to create greater accountability, conditioning financing on verified service delivery has gained increasing attention since the mid-2000s.

How does it work?

Performance-based funding is designed to maximize accountability, transparency, and efficiency of the service provider. Its elements generally include: (a) targets and/or ceilings of repayment, (b) an agreed per-unit payment amount for each output and/or outcome (e.g., new household water connection), and (c) independent verification of results prior to payment disbursement.

Specific performance-based financing instruments include development impact bonds and conditional cash transfers. With conditional cash transfers, cash payments are made directly to needy households to stimulate investment in “human capital” (i.e., the knowledge, skills, and health that people invest in and accumulate throughout their lives to become productive members of society) if they meet predetermined conditions (e.g., periodic health checks or school attendance). Payments can also be structured to incentivize entire communities to achieve a public health or water access goal (Nguyen, Ljung, and Nguyen 2014).

Examples

Encouraging water-related examples have emerged on a limited scale in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, although this approach may not offer advantages under all circumstances

The World Bank established its Global Partnership on Output-based Aid in 2003, renamed in 2019 to the Global Partnership for Results-Based Approaches (World Bank 2022). As of 2022, the Global Partnership portfolio includes 58 individual projects in 30 countries, with more than 12 million verified beneficiaries as well as an array of technical assistance and knowledge activities (World Bank 2022). In Kenya, for example, the national government, World Bank, USAID Development Credit Authority, and Dutch development bank KfW’s Aid on Delivery program support the Water Services Trust Fund of Kenya (Advani 2016). It offers water service providers access to results-based finance to invest in pro-poor water infrastructure, such as urban household connections and public water kiosks. Service providers agree to meet targets for higher consumer consumptions, increased revenue, and reduced water losses.

The UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (formerly called the Department for International Development) has long led performance-based funding approaches, having supported the Global Partnership since its inception while building its own results-based funding portfolio with more than $2.7 billion invested across 19 programs as of 2016 (Clist 2019). An approximately $135 million performance-based “WASH Results Programme” has been implemented in South Asia from 2013 to 2022 by Plan International, the Sustainable WASH in Fragile Contexts consortium led by Oxfam, and the Sustainable Sanitation and Hygiene for All program led by SNV (Howard and White 2020).

The Uptime Catalyst Facility, created in 2020, piloted a results-based funding approach for post-construction rural water maintenance services. Its design built upon three metrics (reliable waterpoints, water volume, and local revenue) and eventually arrived at a “revenue matching” contract design, with supplementation of user payments and matching for a portion of locally-generated revenue. Service providers implement water services up front and are remunerated for results achieved, using a payment formula. Standardized contracts and performance metrics make the model easily scalable. Expansion to serve several million people is ongoing in African, Asia, and Latin America (McNicholl et al. 2021)

The UK government and USAID support the National Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Programme in Mozambique (Rudge 2019). It links 40% of a nearly $40 million grant to the government of Mozambique to eight performance indicators, including the number of people in rural areas with access to new improved drinking water infrastructure and the percentage of contracts (works and services) procured at district level. The performance-based approach is being tested in 20 districts in two provinces of Mozambique (Nampula and Zambezia). Initial evaluation found key enablers: alignment with government priorities and effective transfer of responsibility and accountability for implementation by the sub-national government. Key challenges included ensuring domestic increases in financing for capital and operational expenses.

The international NGO, East Meets West (aka Thrive Networks), implemented output-based aid programs in Vietnam. With support from the Global Partnership, they carried out a rural water program in Central Vietnam and a separate activity in the Mekong Delta region (Nguyen, Ljung, and Nguyen, 2014).

Various management models were employed, involving private enterprises, provincial authorities, and East Meets West as the service provider. Supported by the Vietnamese National Target Program for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation since 2013, the program successfully achieved its target for new household water connections. It accomplished this by leveraging local investment through partial subsidies to low-income beneficiaries. Customer satisfaction surveys highlighted the benefits of introducing private water operators, including improved performance with fewer water losses and breakdowns.

While performance-based approaches may not be universally superior financing options, they hold promise when targeted outcomes are well defined, service providers have experience and interest in achieving efficiencies, reliable data sources and monitoring systems are in place, funders allow room for innovation to service providers, and costs can be reliably priced to increase cost effectiveness for donors and enhance operating efficiencies by the implementer.

To access further information on financial innovations for rural water supply in low-resource settings, you can download the complete report HERE.

The information provided on this website is not official U.S. government information and does not represent the views or positions of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the U.S. Government.

References:

- Nguyen, M, P Ljung, and H Nguyen. 2014. “Output-Based Aid for Delivering Wash Services in Vietnam: Ensuring Sustainability and Reaching the Poor.” In Sustainable Water and Sanitation Services for All in a Fast Changing World, 7. Hanoi, Vietnam.

- World Bank 2022. “Annual Report – Global Partnership for Results-Based Approaches.” Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Advani, Rajesh. 2016. “Scaling Up Blended Financing of Water and Sanitation Investments in Kenya.” Knowledge Note. Knowledge for Development. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. https://www.gprba.org/sites/gpoba/files/publication/downloads/Knowledge-Note-Blended-financing-for-water-in-Kenya.pdf

- Clist, Paul. 2019. “Payment by Results in International Development: Evidence from the First Decade.” Development Policy Review 37 (6): 719–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12405.

- Howard, Guy, and Zach White. 2020. “Does Payment by Results Work? Lessons from a Multi-Country Wash Programme.” Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 10 (4): 716–23. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2020.039

- McNicholl, Duncan, Rob Hope, Alex Money, Cliff Nyaga, J Katuva, Johanna Koehler, Patrick Thomson, et al. 2021. “Delivering Global Rural Water Services through Results-Based Contracts.” Working Paper. UpTime.

- Rudge, L. 2019. “Performance-Based Financing and Capacity Building to Strengthen Wash Systems in Mozambique: Early Findings.” The Hague, the Netherlands: IRC.

“Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings” Innovation 3: Water Quality Assurance Funds

Innovation 3: Water Quality Assurance Funds

This blog post is part of a series that summarizes the REAL-Water report, “Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings,” which was developed by The Aquaya Institute and REAL-Water consortium members with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The report specifically focuses on identifying innovative financing mechanisms to tackle the significant challenge of providing safe and sustainable water supply in low-resource rural communities. These communities are characterized by smaller populations, dispersed settlements, and economic disadvantages, which create obstacles for cost recovery and hinder the realization of economies of scale.

Financial innovations have emerged as viable solutions to improve access to water supply services in low-resource settings. The REAL-Water report identifies seven financing or funding concepts that have the potential to address water supply challenges in rural communities:

- Village Savings for Water

- Digital Financial Services

- Water Quality Assurance Funds

- Performance-Based Funding

- Development Impact Bonds

- Standardized Life-Cycle Costing

- Blending Public/Private Finance

Understanding Water Quality Assurance Funds

In rural areas, community-managed water supplies are increasingly recognized as unsustainable, in part because communities with small water systems (e.g., handpumps, mechanized boreholes, and small piped systems) often struggle to collect enough money to maintain water infrastructure (Whaley et al. 2019). As a result, they typically must neglect critical aspects of professional water management, such as water quality testing to verify its safety for human consumption. Rural agricultural communities, situated far from public or private laboratories, struggle to access testing services due to distance and irregular income patterns. However, a viable solution comes in the form of introducing a third-party guarantor to distribute the risks associated with unpaid water testing fees among various stakeholders (Halvorson-Quevedo and Mirabile 2014). The third party can help to facilitate testing arrangements and provide indirect financial support, wherein stand-by funds are only accessed when the local fee-for-service exchange is disrupted.

How does it work?

“Assurance funds” provide liquid assets (e.g., a savings account) that can be quickly mobilized if a liability arises. Water quality assurance funds are held by a third party (e.g., a nongovernmental organization) to guarantee payment for to the beneficiary (e.g., a centrally located water quality laboratory) if a rural community is unable to pay for water testing services on time (Press-Williams et al. 2021).

By employing this innovative model, larger professional laboratories can extend low-cost centralized monitoring services to smaller rural water systems, fostering efficiency and incentivizing wider-scale testing. As a result, laboratories gain a new market for their services while rural communities gain a reliable means of verifying their drinking water safety with greater certainty and lower startup cost than establishing onsite laboratory capacity.The assurance fund accounting is managed by the third party and can be drawn down

slowly, leveraging donor aid, or replenished if the rural community is able to pay back service fees at a later date (Figure 1). Contract enforcement is managed through the local government authorities.

Figure 1. Simplified illustration of a water quality assurance fund mechanism (Source: Vanessa Guenther, The Aquaya Institute)

Implementation of assurance funds requires diligent management to ensure accountability. Skilled staff must manage the fund as long as it exists.For water quality assurance funds, field and laboratory staff must adhere to good protocols to ensure water quality data are accurate and address decision-making needs in a timely manner.

Examples

Pilot examples come from a few African countries:

With funding support from the Hilton Foundation, The Aquaya Institute (a nonprofit research and consulting organization) developed an assurance fund in 2020 to encourage an existing laboratory to provide water quality monitoring services to small rural water systems in the Asutifi North District of Ghana (Figure 2; Press-Williams et al. 2021). The water systems mobilized community-collected water fees to pay Ghana Water Company Limited’s (GWCL’s) central laboratory (Figure 3) for monthly services. If they defaulted on payments, then GWCL could file a claim against the assurance fund. This centralized testing approach cost an average of $67 per test, or approximately 60% of what it would have cost to provide training and testing equipment for each separate water system.

Between March 2020 and January 2021, GWCL testing revealed microbial contamination in more than half of the 134 water samples across nine water systems, raising awareness among water system managers about issues with chlorination procedures (Press-Williams et al. 2021). In most cases, water systems were able to pay GWCL within one month of receiving testing services. Despite payments being delayed for approximately one third of testing services, GWCL filed only one claim against the assurance fund, instead negotiating directly with the defaulting water systems to allow more time. Extension of the same concept to other districts in

Ghana as well as in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania is underway with additional funding support from USAID REAL Water, the Hilton Foundation, and the Helmsley Charitable Trust. Another use of the assurance fund was to deliver targeted subsidies for specific communities during times of need (e.g., Covid-19 pandemic, fuel price inflation).

Figure 2. Ghana Water Company Limited analyzes bacteria in drinking water samples from small water systems in the nearby rural district of Asutifi North. (Source: Bashiru Yachori, Aquaya Institute).

Figure 3. A Ghana Water Company Limited technician collects a sample from a water point in Asutifi North, Ghana, as part of the Water Quality Assurance Fund agreement (Source: Bashiru Yachori, Aquaya Institute).

To access further information on financial innovations for rural water supply in low-resource settings, you can download the complete report HERE.

The information provided on this website is not official U.S. government information and does not represent the views or positions of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the U.S. Government.

References:

Halvorson-Quevedo, Raundi, and Mariana Mirabile. 2014. “Guarantees for Development.”

Whaley, Luke, Donald John MacAllister, Helen Bonsor, Evance Mwathunga, Sembeyawo Banda, Felece Katusiime, Yehualaeshet Tadesse, Frances Cleaver, and Alan MacDonald. 2019. “Evidence, Ideology, and the Policy of Community Management in Africa.” Environmental Research Letters 14 (8): 085013. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab35be

“Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings” Innovation 2: Digital financial services

This blog post is part of a series that summarizes the REAL-Water report, “Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings,” which was developed by The Aquaya Institute and REAL-Water consortium members with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The report specifically focuses on identifying innovative financing mechanisms to tackle the significant challenge of providing safe and sustainable water supply in low-resource rural communities. These communities are characterized by smaller populations, dispersed settlements, and economic disadvantages, which create obstacles to cost recovery and hinder the realization of economies of scale.

Financial innovations have emerged as viable solutions to improve access to water supply services in low-resource settings. The REAL-Water report identifies seven financing or funding concepts that have the potential to address water supply challenges in rural communities:

- Village Savings for Water

- Digital Financial Services

- Water Quality Assurance Funds

- Performance-Based Funding

- Development Impact Bonds

- Standardized Life-Cycle Costing

- Blending Public/Private Finance

Understanding Digital financial services

Digital financial services have penetrated many aspects of daily life, including water services.

One strategy to address the gap in rural water funding is to increase the financial sustainability of water systems through improved water revenue collection and management (Waldron and Sotiriou 2017). In low-income countries, the collection of service fees primarily relies on cash, which can be labor-intensive, difficult to track, prone to miscalculations, and susceptible to theft or loss (Sharma, 2019). However, by implementing automated digital recording of time-stamped water usage and payment data, the planning, projection, and delivery of water services can be significantly improved (Waldron et al., 2019).Good record-keeping aids water service providers in tracking performance changes over time, as well as supporting financial sustainability, water conservation, and climate adaptation.

How does it work?

“Digital financial services” encompasses two concepts: financial services (e.g., payments,

savings, credit, insurance, user suport) and the technologies that deliver them to end users (Waldron et al. 2019). Services such as online savings or credit accounts mainly benefit adults who work outside the home and have bank accounts (Coulibaly 2021). The digital technologies accessible to users who rely on cash may include mobile money (electronic wallets using a mobile phone), water sale kiosks or “ATMs,” and prepaid token technologies (REAL-Water 2022).

Customers can use digital mechanisms to conveniently purchase water, reducing waiting times and operational downtimes when live vendors or caretakers are unavailable (Waldron et al., 2019). With prepaid digital services, the efficiency of water fee collection can reach nearly 100% (with the exception of targeted subsidies or discounts). “Postpaid” digital financial services, which collect fees retrospectively for prior water usage, enable service providers to automatically track outstanding payments and initiate billing. Digitization may enable better payment compliance, as those with seasonal or inconsistent income are able to deposit a sum of money and draw on it over time (Sharma 2019).

Moreover, the implementation of prepaid metering for automated water dispensing devices and postpaid digital water service accounting brings benefits to both water system operators and customers, improving fee collection consistency as well as convenience. They may likewise simplify subsidy delivery to vulnerable customer segments.

Figure 1. Training a customer in Ruiru, Kenya on how to use his phone for making

water payments (Source: Joyce Kisiangani, The Aquaya Institute)

Examples

Technology provider Grundfos partnered with the nongovernmental organization World Vision and Safaricom, the leading telecommunications provider in Kenya, to install 32 self-service water kiosks (called LifeLink systems) in locations that lacked water infrastructure, serving both

homes and businesses (Waldron et al. 2019). Initial uptake was high and interviews documented user benefits from reduced favoritism in water distribution as well as being able to track and review spending. Collecting mobile payments cost less than collecting cash payments, a savings that could be reinvested to upgrade services or passed onto consumers (Sharma 2019). The World Bank and others have likewise been working to scale affordable water installations in Tanzania using prepaid Grundfos card kiosks combined with solar pumping, which vastly reduces water transportation time and stabilizes high prices offered by private sellers (World Bank 2017). Recognized downsides of this and other digital payment examples have included questions of who requires data access, remote monitoring needs, labor cuts, reduced customer service capabilities, and difficulty paying among the ultra-poor (Waldron et al. 2019).

The nonprofit organization Safe Water Network uses Hangzhou LAISON Technology digital household prepaid meters in their piped connection program in Ghana. Customers receive a device to input a token purchased through mobile money. New users joined quickly following customer workshops to explain the payment system, and the enhanced cost recovery shifted the operation from a net loss to a net surplus (Waldron et al. 2019). Ensuring proper use will likely require sustained engagement. Safe Water Network has continued expanding the household connection metering program to serve several thousand households in small rural towns in Ghana’s Ashanti Region.

Transitioning to digital payments comes with certain challenges, such as additional transaction fees, costly startup infrastructure, poor telecommunications technology, skepticism towards technology, and the belief that water services should be cheaper or free, as well as income loss for traditional vendors who primarily handle cash transactions. Local training support and outreach efforts for social inclusion can be beneficial for expanding digital services. However, digital financial services do not represent a fix-all solution. Their successful implementation requires substantial training and effective governance to transition service providers and communities to new processes that increase collection efficiency, while minimizing the impact on customers’ water usage (Heymans, Eales, and Franceys, 2014).

Digital financial service innovations have made inroads globally in urban areas and are rapidly expanding to serve rural residents in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. As use expands, social inclusion efforts may be needed to ensure the services benefit vulnerable populations (Coulibaly 2021).

To access further information on financial innovations for rural water supply in low-resource settings, you can download the complete report HERE.

The information provided on this website is not official U.S. government information and does not represent the views or positions of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the U.S. Government.

References:

“Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings” Innovation 1 – Village Savings for Water

Innovation 1: Village Savings for Water

This blog post is part of a series that summarizes the REAL-Water report, “Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings,” which was developed by The Aquaya Institute and REAL-Water consortium members with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The report specifically focuses on identifying innovative financing mechanisms to tackle the significant challenge of providing safe and sustainable water supply in low-resource rural communities. These communities are characterized by smaller populations, dispersed settlements, and economic disadvantages, which create obstacles for cost recovery and hinder the realization of economies of scale.

Financial innovations have emerged as viable solutions to improve access to water supply services in low-resource settings. The REAL-Water report identifies seven financing or funding concepts that have the potential to address water supply challenges in rural communities:

- Village Savings for Water

- Digital Financial Services

- Water Quality Assurance Funds

- Performance-Based Funding

- Development Impact Bonds

- Standardized Life-Cycle Costing

- Blending Public/Private Finance

Understanding Village Savings for Water

Community-based savings and credit associations offer rural dwellers in low-income settings an opportunity for member-only access to loans, emergency support, and small annual investment returns. With abundant existing savings groups in sub-Saharan Africa and India, the mechanism has been leveraged in some cases to improve financial management of rural water systems. They offer a framework for creating dedicated, affordable, and transparent savings funds to pay for high-quality maintenance and repairs. Groups may dissolve over time, though, and require periodic external support. Field results from limited-scale water initiatives in several African countries have maintained an above-average reserve fund to support water point maintenance, repairs, or upgrades (The Water Trust 2022).

How does it work?

One low-barrier approach to improve funding for water system maintenance shifts financial management duties from volunteer water committees to new or existing community-based savings and credit associations. These self-selected, self-governed groups offer rural residents informal yet structured financial services with several built-in accountability mechanisms. Groups made up of 5–40 members usually operate on a 12-month cycle (VSL Associates 2022; Orr et al. 2019; Allen and Panetta 2010; Swinderen et al. 2020). At the beginning of each cycle, the group develops a constitution, defining savings and borrowing terms along with group bylaws (Figure 1). At weekly or monthly meetings, each member deposits the agreed amount of money into a common fund. Members can then take small, low-interest loans from this internally-generated capital. At the end of the cycle, each member receives their savings plus a portion of the overall interest earned from loans. Many savings groups offer a small mutual insurance scheme as well, using funds to provide allowances or no-interest loans in the case of unexpected member hardships (e.g., family illness or death).

Figure 1. Typical community savings group approach (Source: Vanessa Guenther, The Aquaya Institute)

The saving group model offers several advantages, including transparency, accountability, and trust-building among members. Successful implementation examples in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Uganda, have demonstrated their positive impact on water point management. By integrating savings groups, water user committees have reinforced accountability and improved the community’s commitment to paying for water services.

However, this model also faces challenges, such as limited capacity and technical expertise, the potential disintegration of savings groups, and the need for ongoing subsidization of maintenance services. While there may be initial costs associated with establishing savings groups, the return on investment can be significant. For instance, external support costs for savings group startup could exceed $1,000 per system, with a longer time frame needed to observe returns in the form of a sustained water fund (The Aquaya Institute, in press); however, the return on investment considering all-purpose savings can reach up to 20:1 (Krause 2022).

Examples

In sub-Saharan Africa, savings groups have been utilized to support water point management. In the Lira district of Northern Uganda, existing water user committees began offering small loans for personal needs, which reinforced their record-keeping accountability as well as the community’s commitment to paying monthly for water services (Nabunnya et al. 2012). Challenges included some refusal to pay for water and the informal process and money handling approach (by the local volunteer treasurer). In the Kamwenge district of southwestern Uganda, Water for People trained communities on financial planning for water point breakdowns, with savings groups as one of the strategy options (Muhangi 2018). Additional Ugandan examples come from Link to Progress (Piracel 2021), The Aquaya Institute (Marshall, Guenther, and Delaire 2021), WE Consult and Charity Water, Lifewater International, and Amref (Teo 2016). SEND has supported savings groups in Sierra Leone (SEND 2020), while the USAID West Africa Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Program (USAID ND) and the nongovernmental organization WaSaDev have supported savings groups in Ghana.

In Malawian “borehole banking,” a central account is established at a water point and contributions are made through monthly water user fees. Then, community members who contribute can access loans, to be paid back with interest to the water point account (Mbewe 2018).

A pilot of 175 water points with “borehole banks” achieved an average savings of approximately $80 for operation and maintenance, about ten times higher than the average savings reported for water points without borehole banks. The rate of functionality increased from 64% to 94% between 2015 and 2017.

In another program from Uganda, The Water Trust worked with VSLAs to set aside an agreed-upon fraction of members’ payments earmarked as a “water point reserve fund,” which can only be used for handpump maintenance. Monitoring results have been encouraging: in the 2017 pilot, 32 water points with VSLA-based water funds had collected an annual average fund about four times greater than 28 communities relying on coached water user committees or a maintenance contract approach alone (Prottas, Dioguardi, and Aguti 2018). By 2020, The Water Trust invested training resources to extend the approach to more than 200 communities, with annual reserve funds continuing to meet or exceed target amounts (The Water Trust 2020). The approach has expanded to cover more than 700 water points, documenting higher measures of water point functionality and active water point management for water points with an associated VSLA (The Water Trust 2022).

Figure 2. Village Savings and Loan Association members in the Kabarole district, Uganda, holding up their passbooks (Source: Katherine Marshall, The Aquaya Institute)

Although the concept of using savings groups to mobilize and manage water point funds has existed for several years (Agbenorheri and Fonseca 2005), this approach is not yet common and remains in the early stages of evaluation research (e.g., by The Water Trust and The Aquaya Institute). Despite compelling examples, its application to serve rural water supply services is globally limited. The knowledge base comes almost exclusively from implementation experience, with fewer examples of rigorous evaluation at scale. Improved documentation would improve the sector’s understanding of how to most effectively leverage community savings groups to improve rural water services.

Savings groups supporting water point management are of interest to government service providers and NGOs offering subsidies. Rural service providers facing challenges with inconsistent user payments should consider experimenting with community savings groups, particularly in areas where pay-as-you-fetch systems are underperforming, such as communities served by public handpumps (Marshall, Guenther, and Delaire 2021). Danert (2022) estimates that approximately 20% (ranging from 1%–60%, by country) of sub-Saharan

Africa’s population relies on handpumps. Additional opportunities arise in communities with gravity flow schemes and mechanized boreholes that have regularly struggled to collect revenue.

To access further information on financial innovations for rural water supply in low-resource settings, you can download the complete report HERE.

The information provided on this website is not official U.S. government information and does not represent the views or positions of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the U.S. Government.

References:

The Water Trust. 2022. “Improving Water Point Functionality in Rural Uganda through Self-Help Groups: A Cross-Sectional Study.” The Water Trust.

VSL Associates. 2022. “VSL Associates – Who We Are.” VSLA. 2022.

New REAL-Water activity: Water Sustainability in Southern Madagascar

REAL-Water to coordinate data and actions for the sustainable development of water resources in arid Southern Madagascar.

In Madagascar, there are significant disparities in access to essential water and sanitation services. Currently, only about half of the population (54.4%) has access to vital water services, and just over 10% have access to necessary sanitation services. The situation is particularly challenging in Southern Madagascar, where various development issues, such as population growth, changes in land use, and worsening dry-season water shortages, are present. These difficulties are exacerbated by poverty, which hinders water resource development, leads to poor infrastructure, and contributes to food insecurity.

To guide regional programming that considers the development and humanitarian requirements, USAID Madagascar has commissioned REAL-Water to assess water resources and infrastructure needs. The program will entail specific activities, including a literature review of water development activities, data collection on existing and planned water infrastructure, analyses of remaining water resources and infrastructure needs, and planning for future investments.

Un fondo de préstamos de mil millones de dólares y el camino hacia unos servicios de agua mejor gestionados

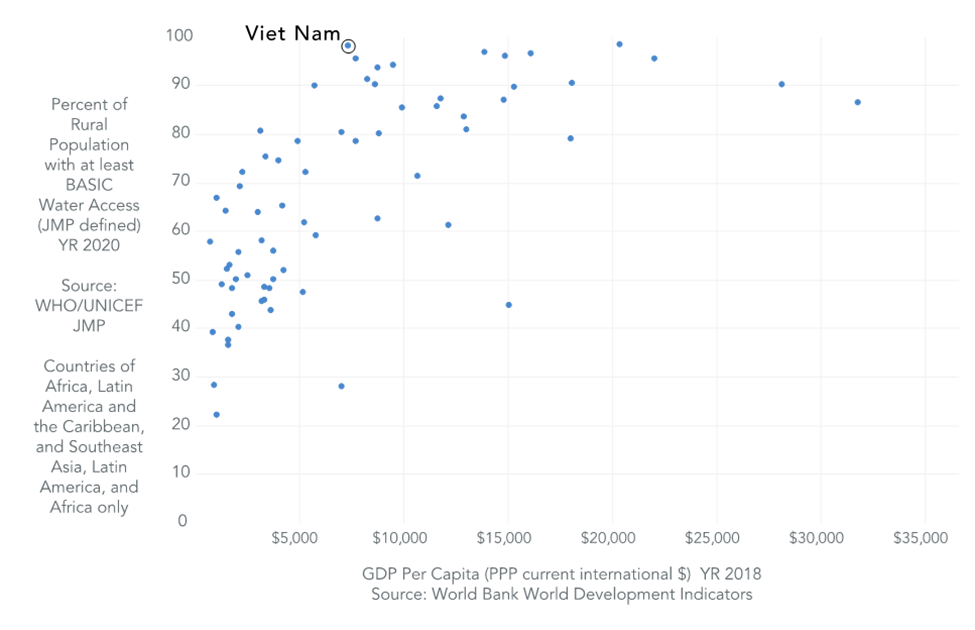

As of 2020, Vietnam had the highest levels of rural water coverage among any country of comparable economic level, with coverage equivalent to countries with two to three times its per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP). We were curious: what was the contribution to this success by the billion dollar Asian Development Bank Water Sector Investment Fund (“the Fund”)?

de USAID Global Waters. La RWSN es miembro del consorcio de investigación REAL-Water

En 2020, Vietnam contaba con los niveles más altos de cobertura de agua rural entre cualquier país de nivel económico comparable, con una cobertura equivalente a la de países con dos o tres veces su Producto Interior Bruto (PIB) per cápita. Sentimos curiosidad: ¿cuál fue la contribución a este éxito del Fondo de Inversión en el Sector del Agua del Banco Asiático de Desarrollo, dotado con mil millones de dólares (“el Fondo”)?

Para responder a esta pregunta, invitamos a Hubert Jenny, antiguo miembro del Banco Asiático de Desarrollo (BAD) y actual consultor de UNICEF, a una conversación en el podcast de REAL-Water (disponible en inglés en Anchor, Spotify, y Apple Podcasts, entre otras plataformas).

Continue reading “Un fondo de préstamos de mil millones de dólares y el camino hacia unos servicios de agua mejor gestionados”