Guest blog by Rebecca Laes-Kushner. Featured photo from RWSN webinar presentation on 29.4.25 (What Drives the Performance of Rural Piped Water Supply Facilities?) by Babacar Gueye from GRET Senegal.

Professionalism. Standards. Systems. These themes are repeated throughout Rural Water Supply Network’s (RWSN) spring and fall 2025 webinar series.

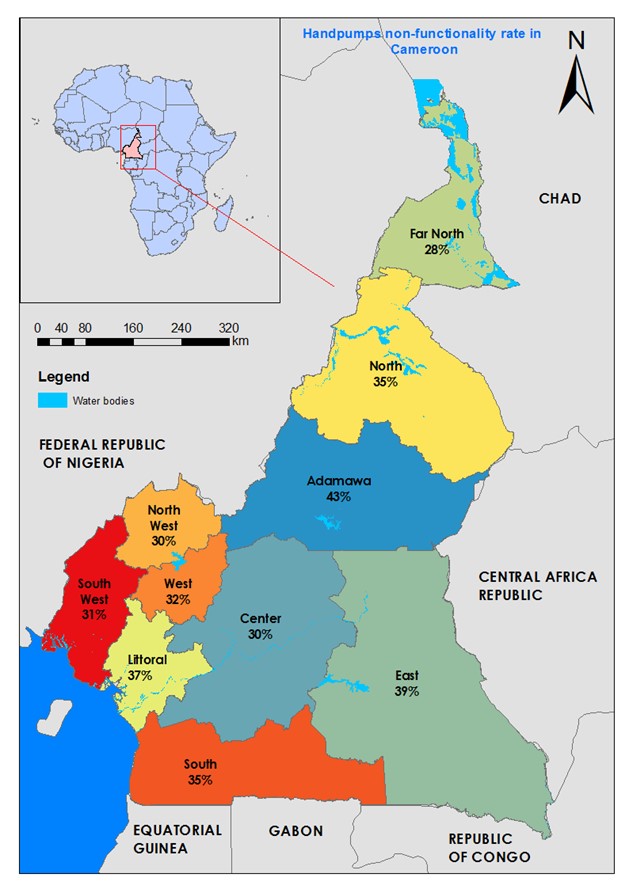

Given the large percentage of boreholes with early failure – within one to two years – improvements in standards and professionalism in borehole drilling are necessary. Drilling association leaders spoke passionately about the need for borehole drillers to professionalize to improve the quality of boreholes, increase accountability, stop illegal drilling and enhance community buy-in, which occurs when standards are enforced and certified materials are used.

George k’Ouma, from the Small Scale Drillers Association of Kenya, said it best: Professionalism isn’t optional.

| A tidbit: Small borehole drillers have an advantage over large operations because they have knowledge of the local geology and seasonal changes, which enables better planning and materials selection. |

Another area in need of increased professionalism is water management. Professor Kwabena Nyarko, from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi (KNUST), conducted a study comparing public sector, private sector and community water management in Ghana. Model type was less important than having professional standards and following best practices, including metering, tariffs that covered maintenance costs, efficient collection of tariffs, audits and reporting, digital recordkeeping and training, as well as financial support.

Jose Kobashikawa, head of the Enforcement Directorate for Sunass, the regulatory body for drinking water and sanitation services in Peru, echoed these concepts in his presentation. SUNASS uses a benchmarking tool to evaluate rural providers. Metrics include formality and management (are they registered, do they have a water use license), financial sustainability (do they collect tariffs, what percent of customers are defaulters), and quality of services (is water chlorinated and daily hours of water supply). High performing providers are awarded certificates recognizing their good practices in public management and workshops are held in each region to disseminate best practices.

Focusing on systems is another thread that runs through the varied webinar topics. Systems thinking means designing a scheme for the long-term provision of water. Boreholes must be properly sited. Appropriate materials, such as high quality stainless steel (304/316), need to be selected in order to prevent corrosion, as RWSN’s Stop the Rot initiative details. Handpumps often corrode within months or years instead of lasting a decade. Ayebale Ared, Technical and Social Expert at Welthungerhilfe, shared Uganda’s systemic solution: in 2016 the country banned the use of galvanized iron (GI) risers and rods in all new and rehabilitated handpumps – the first sub-Saharan country to do so. Uganda also requires a water quality analysis be done before materials are selected.

In addition, data collection and use must be embedded in all stages and aspects of water projects.. Dr. Callist Tindimugaya, Commissioner for Water Resources Planning and Regulation in Uganda, collects data from drillers which he then turns into groundwater maps the drillers can then use.

Systems thinking also means including the needs of the entire population in the design, especially women, who bear the burden of hauling and carrying water. Women – who are killed by crocodiles while washing clothes in rivers, whose skin is irritated by harsh detergents, who find leaning over low wash basins harder as they age, who need to wash bloody clothes and bedsheets separately from the family’s regular laundry when they menstruate. Laundry is barely mentioned in WASH circles but RWSN devoted an entire webinar to the topic. One speaker questioned how the WASH sector would be different if the metric for success was the amount of time women spend collecting water.

Understanding the local culture is critical; psychologists, behaviorists and sociologists can help provide insights. Technical solutions which aren’t accepted by the community will only lead to failure.

The lack of funds to cover maintenance work on wells is well known. Systems thinking means anticipating root causes of funding issues in a community and pre-emptively building a system that attempts to solve those issues. Tariffs are too low to cover maintenance? Then the project needs to determine how sufficient funds will be raised, whether through higher water fees (that may be less affordable to low-income families) or from external sources. The water committee is inefficient at collecting funds? Then training and capacity building need to be part of the project design from the beginning.

Looking at the bigger picture helps creative ideas flourish: Household rainwater harvesting, replenishing water aquifers through tube recharging, deep bed farming that breaks up the hard pan so water can return to the aquifer, sand dams that filter water and incorporating water management and regreening in the design and construction of roads so crops can grow next to roads. During the laundry webinar, three organizations presented their laundry solutions – devices that save women time, eliminate much of the manual labor, use less water and even offer income-generating opportunities.

The webinars are at times frustrating because we clearly know what needs to be done – yet professionalism, systems thinking and best practices are not always prevalent. More often, though, the webinars are full of insightful information and inspiring stores from experts. The knowledgeable participants, who ask focused, detailed questions, enhance the experience. I look forward to the spring 2026 webinars which are currently being planned.

Rebecca Laes-Kushner is a consultant to NGOs and companies with a social mission, with a particular focus on development issues such as WASH, climate change, supporting SMEs, health care and nutrition. Laes-Kushner Consulting (https://laeskushner.net/) provides research and writing, data analysis, M&E and training services. Rebecca has a Master’s in Public Administration (USA) and a Certificate of Advanced Studies in Development and Cooperation from ETH NADEL in Switzerland.