by Gian Melloni, Maria Livia De Rubeis, and Kristina Nilsson of the DRC WASH Consortium

In 2013, the idea of rural communities paying for water services was relatively new in DRC: there was a belief in the WASH sector that this context was too fragile for community management of WASH services to be possible.Yet with extremely low access rates, a fast-growing population, and especially poor functionality of water infrastructure, something needed to change.

When the DRC WASH Consortium started that same year, there was no past experience in the country which could confirm rural communities’ willingness or ability to pay for water. The DRC WASH Consortium’s ambitions were high: five INGOs launching a six year programme to support local communities in managing and financially sustaining WASH services in rural DRC. Funded by UK-aid, the DRC WASH Consortium gathered the know-how of lead agency Concern Worldwide with ACF, ACTED, CRS, and Solidarités International to work with more than 600 rural communities and 640,000 people across seven provinces.

Five years later, with a wealth of project data at our disposal, we wanted to answer some key questions: To what extent do Consortium-assisted rural communities succeed in managing their water services in a financially self-sufficient way? And what makes a community successful?

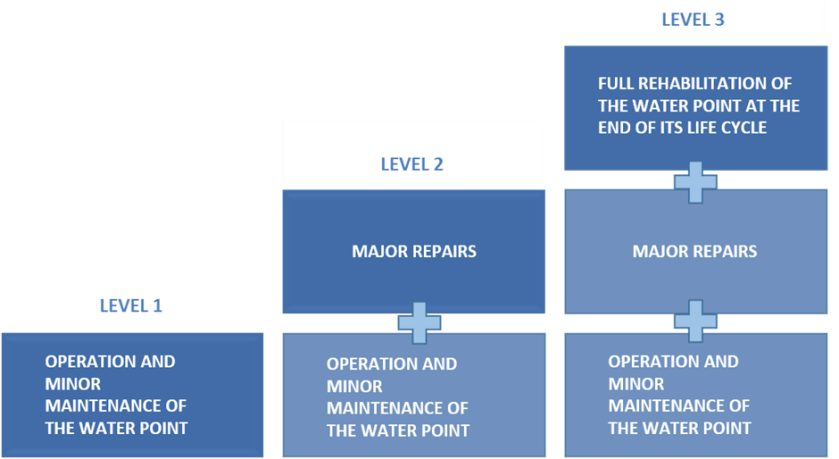

The DRC WASH Consortium developed a methodology inspired by IRC’s Life-Cycle Costs, which we call the “Economic Approach”. We support communities in developing managerial, financial and technical skills to keep their WASH infrastructure functioning long after construction, identifying three progressive levels of success in covering the costs associated with water points over time:

The objective is that communities raise sufficient funds to cover Level 1 costs as a minimum, with the most committed communities reaching Levels 2 and 3. These funds are collected and managed by elected committees, trained by the DRC WASH Consortium. To lay the foundations for this success and to avoid expectations of handouts, we’ve said from the start: we will support communities by installing water points only if they prove their commitment and ability to take care of water point management costs afterwards.

Our three Economic Approach Levels do not exactly match with the Life-Cycle Costs categories, and some modifications have been made according to the context in rural DRC. Here you can see an approximate conversion table showing how the DRC WASH Consortium adapted these principles:

And does this Economic Approach work? After five years, our program data shows it can, even in this difficult context: so far, about two thirds of the small rural communities assisted by the DRC WASH Consortium have succeeded in achieving a degree of financial self-sufficiency and sustainability –that is to say, have reached at least Level 1. Given the challenges these communities (typically of only around 1,000 people) in this fragile environment face, this is an encouraging provisional result.

We’ve identified some operational models which support WASH committees in reaching these Levels. Committees that have chosen diversified revenue streams, combining household collections with revenue-generating activities, are markedly more successful than committees relying only on collections. This approach is often welcomed by communities who see investments in revenue-generating activities as a means to protect finances against misappropriations. Overall, revenue-generating activities seem to fit well with community management of WASH services in rural DRC.

In such a fragile context, most communities choose to identify people or groups who may be particularly vulnerable and offer them exemptions from paying community water fees. Communities who do so are no less successful in reaching the Levels of financial self-sufficiency than communities who do not offer exemptions. This is an important finding particularly in light of pro-poor and needs-based principles of development, underlining that aiming for equitable access isn’t at odds with the practice of paying for water or the goal of sustainable services.

Communities opting to remunerate some water management committee members also seem to improve their success in reaching higher Levels of financial self-sufficiency. For example, some communities pay a minimal amount to someone who keeps records of water users or who collects payments. While so far a minority of communities have opted for these remuneration systems, their success in reaching especially Levels 2 and 3 suggests some form of semi-professionalised management can be more effective than pure volunteerism.

Overall, this shows that development actors even in difficult contexts can and should design WASH interventions to focus on longer-term services, looking beyond just immediate achievements. It shows policy-makers can embrace water service payments by users even while balancing financial viability of services with pro-poor and inclusive policies. We have learned through the DRC WASH Consortium that rural communities in DRC are willing to invest to overcome challenges and can develop the capacities to manage water services in a sustainable manner. This doesn’t come easily or by chance, but through carefully designed and implemented programming which empowers local communities.

Feature photo: A WASH management committee in Manono, Tanganyika province, DRC, looks at the financial records they keep to monitor costs and revenues for managing their community water point. Source: DRC WASH Consortium, 2016

The DRC WASH Consortium is a programme of Concern Worldwide in consortium with ACF, ACTED, CRS, and Solidarités International, and funded by UK-aid. More information – in both French and English – can be found at consortiumwashrdc.net. Gian Melloni is the Director of the DRC WASH Consortium and can be reached at gian.melloni (at) concern.net. Maria Livia De Rubeis is the Communication, Advocacy and Learning Manager. Kristina Nilsson is the Monitoring and Evaluation Manager. The views expressed by the authors may not reflect the views of Concern Worldwide or of any of the organisations mentioned.

Course modules

Course modules