By Adrian Cullis

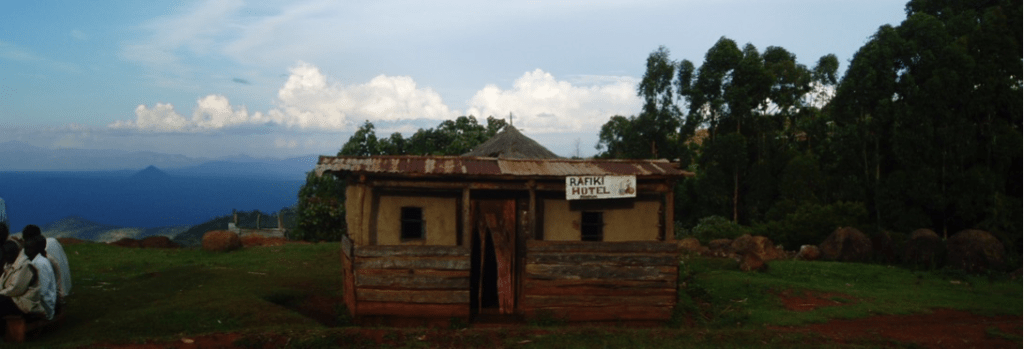

In her January 2025 blog – the first in a 24-part series, of which this is the sixth – Kerstin recalled looking out from Kaproron’s cliffs on the slopes of Mt. Elgon, across the dry plains of Karamoja, and reflecting on the derogatory language so often used to describe these pastoralists in Uganda’s extreme north-east.

What I hadn’t recognised until reading her blog was that, while she was looking north, we were often passing Mt. Elgon on our way to Kampala from our home in Moroto. At that time I was working with the Karamoja Agro-Pastoral Development Project (KADP) under the Lutheran World Federation (LWF). LWF had established its base in Moroto in the early 1980s, responding to the humanitarian crisis that followed 1979-80 when cattle raiding, livestock disease, and general instability had pushed the region to the brink of famine.

By the time I joined LWF in Moroto in the mid-1990s, their emergency response had evolved into a more integrated development program, with components on water development, agriculture, women’s empowerment, and peacebuilding.

At the heart of the water programme was Tom O., a quiet, gifted engineer from West Nile. Tom and his team brought more than groundwater to the surface – they established trust through the hundreds of boreholes that they drilled from Kaabong in the north to Namalu in the south. During a 2024 return to Karamoja, I met a pump mechanic trained by Tom nearly 30 years ago, who proudly showed me still-functioning boreholes drilled by Tom and his team that he’d maintained over the years.

There are however inevitable catches.

On that same 2024 visit, in the very next village from the pump mechanic’s home, we encountered a very different scenario: a cluster of seven failed boreholes. The Tufts University team I was working with was initially sceptical – seven? really? – until the story emerged: a well-connected sub-county official had repeatedly redirected drilling rigs toward his land, each time hoping the new rig would succeed where others had failed. He, of course, hadn’t shared the stories of those previous failures.

This kind of manipulation would, one hopes, be harder to pull off today. Uganda’s district-level computing and data capacity has grown exponentially, so in theory at least planners and engineers have ready access to every dataset they might need: hydrogeology, settlement patterns, borehole histories, yields, maintenance logs. In theory. In practice of course, data often exist in silos, are scattered, outdated, or sitting unread on a hard drive few can access and even fewer think of updating.

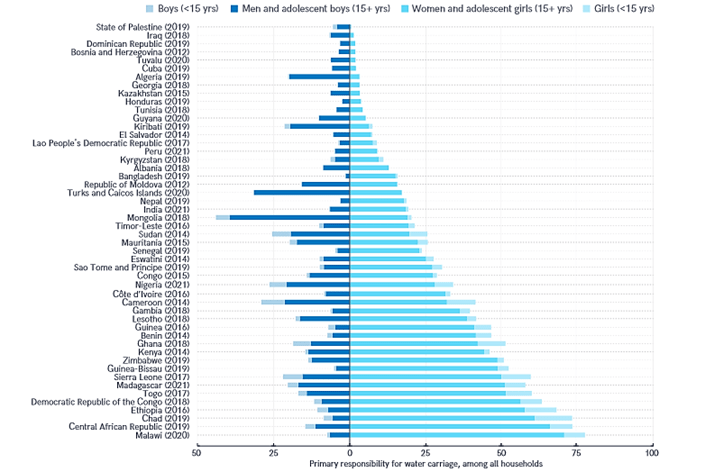

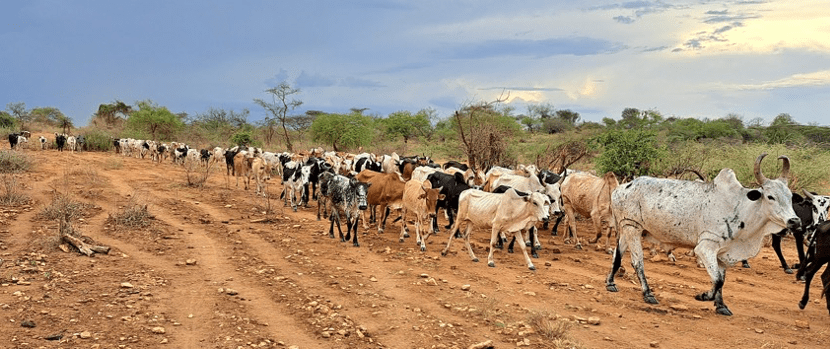

But I think more troubling than the data challenges is a conceptual one – especially in how water development is approached in pastoralist regions like Karamoja, where people move with their livestock. The prevailing logic goes something like this: pastoralists are but one of several vulnerable groups, and so with other vulnerable groups they should share water points. In principle, this sounds inclusive. In practice, it’s exclusion by dilution. Why? Because these pastoralists move. Their seasonal mobility means they’re often absent when decisions about ‘shared’ water points are made and, over time, these absences become a disadvantage. Eventually, ‘shared’ water becomes ‘our’ water, typically, more sedentary households who then transform the surrounding rangelands into fields, settlements, and year-round grazing areas that do far more damage than drought ever could.

And just like that, pastoralists are pushed out – not by an explicit exclusion policy, but by land use practices. Not by violence, but by the quiet erosion of access.

The apparent absence of people or livestock from a landscape is not a void to be filled. It’s a pastoral system at rest – regenerating, recovering, and waiting for the seasonal return of the pastoralists it supports.

If we want water development to work for pastoralists, it must not only support access during seasons of use but also prevent access during seasons of rest. That may sound counterintuitive – even paradoxical – but that’s exactly the point. If then you’re a water engineer, planner or policymaker, please don’t misread seasonal rangeland emptiness as under-utilisation – or worse, as opportunity. It’s not. It’s someone else’s functional rangeland – resting for now.

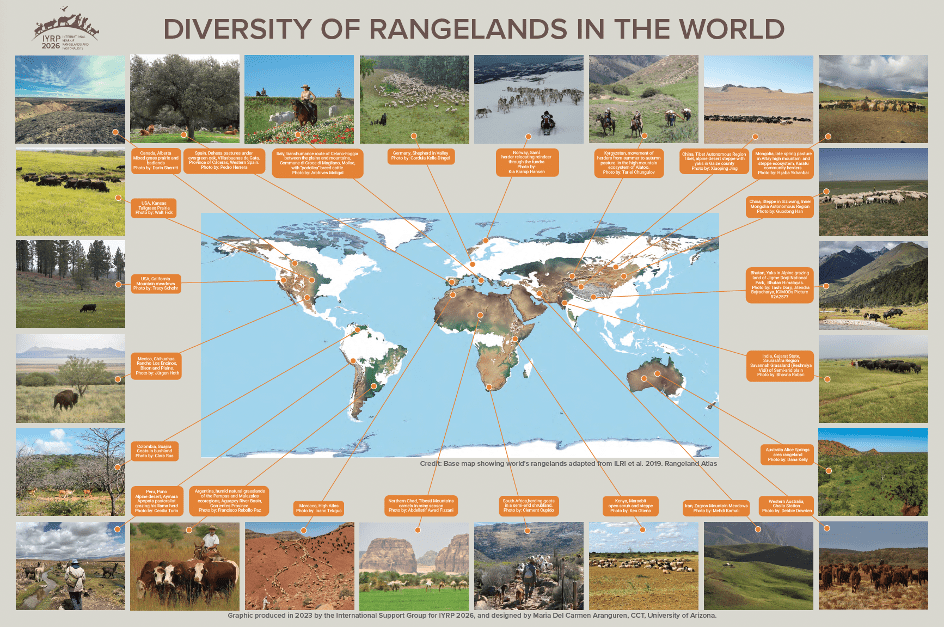

As the 2026 International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists approaches, those of us working in water resource development would do well to shift not just our technologies, but also our thinking. Sometimes, the most responsible form of water development is not to drill at all.

This is part of our blog series on pastoralists and water.