This blog post is part of a series that summarizes the REAL-Water report, “Financial Innovations for Rural Water Supply in Low-Resource Settings,” which was developed by The Aquaya Institute and REAL-Water consortium members with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The report specifically focuses on identifying innovative financing mechanisms to tackle the significant challenge of providing safe and sustainable water supply in low-resource rural communities. These communities are characterized by smaller populations, dispersed settlements, and economic disadvantages, which create obstacles for cost recovery and hinder the realization of economies of scale.

Financial innovations have emerged as viable solutions to improve access to water supply services in low-resource settings. The REAL-Water report identifies seven financing or funding concepts that have the potential to address water supply challenges in rural communities:

- Village Savings for Water

- Digital Financial Services

- Water Quality Assurance Funds

- Performance-Based Funding

- Development Impact Bonds

- Standardized Life-Cycle Costing

- Blending Public/Private Finance

Understanding Performance-based Funding

Many water supply development projects fail due to well-meaning but poorly-executed investments (McNicholl et al. 2019). Repayable water supply investments often risk losses, due to the pervasive challenges of serving low- and middle-income rural settings. Development aid recipients, including governments and water service providers, may face challenges such as limited capacity, oversight, victims of corrupt schemes, or weak governance. These factors can affect the incentives to achieve optimal outcomes. From the funder’s perspective, poor outcomes reinforce high-risk perceptions and may steer resources away from water supply investments. The potential beneficiaries, rural water consumers, suffer the consequences with little opportunity for recourse. As a way to create greater accountability, conditioning financing on verified service delivery has gained increasing attention since the mid-2000s.

How does it work?

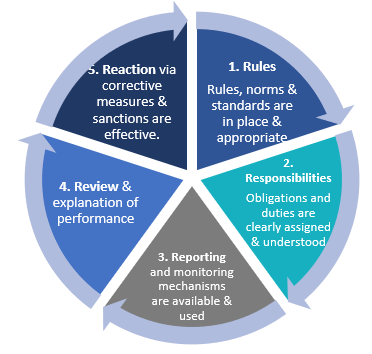

Performance-based funding is designed to maximize accountability, transparency, and efficiency of the service provider. Its elements generally include: (a) targets and/or ceilings of repayment, (b) an agreed per-unit payment amount for each output and/or outcome (e.g., new household water connection), and (c) independent verification of results prior to payment disbursement.

Specific performance-based financing instruments include development impact bonds and conditional cash transfers. With conditional cash transfers, cash payments are made directly to needy households to stimulate investment in “human capital” (i.e., the knowledge, skills, and health that people invest in and accumulate throughout their lives to become productive members of society) if they meet predetermined conditions (e.g., periodic health checks or school attendance). Payments can also be structured to incentivize entire communities to achieve a public health or water access goal (Nguyen, Ljung, and Nguyen 2014).

Examples

Encouraging water-related examples have emerged on a limited scale in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, although this approach may not offer advantages under all circumstances

The World Bank established its Global Partnership on Output-based Aid in 2003, renamed in 2019 to the Global Partnership for Results-Based Approaches (World Bank 2022). As of 2022, the Global Partnership portfolio includes 58 individual projects in 30 countries, with more than 12 million verified beneficiaries as well as an array of technical assistance and knowledge activities (World Bank 2022). In Kenya, for example, the national government, World Bank, USAID Development Credit Authority, and Dutch development bank KfW’s Aid on Delivery program support the Water Services Trust Fund of Kenya (Advani 2016). It offers water service providers access to results-based finance to invest in pro-poor water infrastructure, such as urban household connections and public water kiosks. Service providers agree to meet targets for higher consumer consumptions, increased revenue, and reduced water losses.

The UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (formerly called the Department for International Development) has long led performance-based funding approaches, having supported the Global Partnership since its inception while building its own results-based funding portfolio with more than $2.7 billion invested across 19 programs as of 2016 (Clist 2019). An approximately $135 million performance-based “WASH Results Programme” has been implemented in South Asia from 2013 to 2022 by Plan International, the Sustainable WASH in Fragile Contexts consortium led by Oxfam, and the Sustainable Sanitation and Hygiene for All program led by SNV (Howard and White 2020).

The Uptime Catalyst Facility, created in 2020, piloted a results-based funding approach for post-construction rural water maintenance services. Its design built upon three metrics (reliable waterpoints, water volume, and local revenue) and eventually arrived at a “revenue matching” contract design, with supplementation of user payments and matching for a portion of locally-generated revenue. Service providers implement water services up front and are remunerated for results achieved, using a payment formula. Standardized contracts and performance metrics make the model easily scalable. Expansion to serve several million people is ongoing in African, Asia, and Latin America (McNicholl et al. 2021)

The UK government and USAID support the National Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Programme in Mozambique (Rudge 2019). It links 40% of a nearly $40 million grant to the government of Mozambique to eight performance indicators, including the number of people in rural areas with access to new improved drinking water infrastructure and the percentage of contracts (works and services) procured at district level. The performance-based approach is being tested in 20 districts in two provinces of Mozambique (Nampula and Zambezia). Initial evaluation found key enablers: alignment with government priorities and effective transfer of responsibility and accountability for implementation by the sub-national government. Key challenges included ensuring domestic increases in financing for capital and operational expenses.

The international NGO, East Meets West (aka Thrive Networks), implemented output-based aid programs in Vietnam. With support from the Global Partnership, they carried out a rural water program in Central Vietnam and a separate activity in the Mekong Delta region (Nguyen, Ljung, and Nguyen, 2014).

Various management models were employed, involving private enterprises, provincial authorities, and East Meets West as the service provider. Supported by the Vietnamese National Target Program for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation since 2013, the program successfully achieved its target for new household water connections. It accomplished this by leveraging local investment through partial subsidies to low-income beneficiaries. Customer satisfaction surveys highlighted the benefits of introducing private water operators, including improved performance with fewer water losses and breakdowns.

While performance-based approaches may not be universally superior financing options, they hold promise when targeted outcomes are well defined, service providers have experience and interest in achieving efficiencies, reliable data sources and monitoring systems are in place, funders allow room for innovation to service providers, and costs can be reliably priced to increase cost effectiveness for donors and enhance operating efficiencies by the implementer.

To access further information on financial innovations for rural water supply in low-resource settings, you can download the complete report HERE.

The information provided on this website is not official U.S. government information and does not represent the views or positions of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the U.S. Government.

References:

- Nguyen, M, P Ljung, and H Nguyen. 2014. “Output-Based Aid for Delivering Wash Services in Vietnam: Ensuring Sustainability and Reaching the Poor.” In Sustainable Water and Sanitation Services for All in a Fast Changing World, 7. Hanoi, Vietnam.

- World Bank 2022. “Annual Report – Global Partnership for Results-Based Approaches.” Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Advani, Rajesh. 2016. “Scaling Up Blended Financing of Water and Sanitation Investments in Kenya.” Knowledge Note. Knowledge for Development. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. https://www.gprba.org/sites/gpoba/files/publication/downloads/Knowledge-Note-Blended-financing-for-water-in-Kenya.pdf

- Clist, Paul. 2019. “Payment by Results in International Development: Evidence from the First Decade.” Development Policy Review 37 (6): 719–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12405.

- Howard, Guy, and Zach White. 2020. “Does Payment by Results Work? Lessons from a Multi-Country Wash Programme.” Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 10 (4): 716–23. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2020.039

- McNicholl, Duncan, Rob Hope, Alex Money, Cliff Nyaga, J Katuva, Johanna Koehler, Patrick Thomson, et al. 2021. “Delivering Global Rural Water Services through Results-Based Contracts.” Working Paper. UpTime.

- Rudge, L. 2019. “Performance-Based Financing and Capacity Building to Strengthen Wash Systems in Mozambique: Early Findings.” The Hague, the Netherlands: IRC.