Dr Kerstin Danert [1] with Dr Maryam Niamir-Fuller [2]

In support of the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (IYRP2026) and linkages with water in particular, this is my third in a series of blogs. Here, I start to draw out my highlights from the 2022 webinar on Pastoralists and Water, hosted by RWSN. If you want an introduction to pastoralists, check out my second blog.

In contrast to some of the derogatory comments about pastoralists that I heard in my early working life (see Blog 1), pastoralism is not actually an outmoded way of living from the past at all! In fact, there are strong arguments that it is the solution for a sustainable future. Can this really be true, I ask myself?

In fact, it starts to make sense when you realise that pastoralists specialise in making use of highly variable environments to produce food. By moving with their livestock, they manage continuously changing opportunities for grazing in their landscape. You can learn more in this film, which I find fascinating. It turned some of my perceptions on their head.

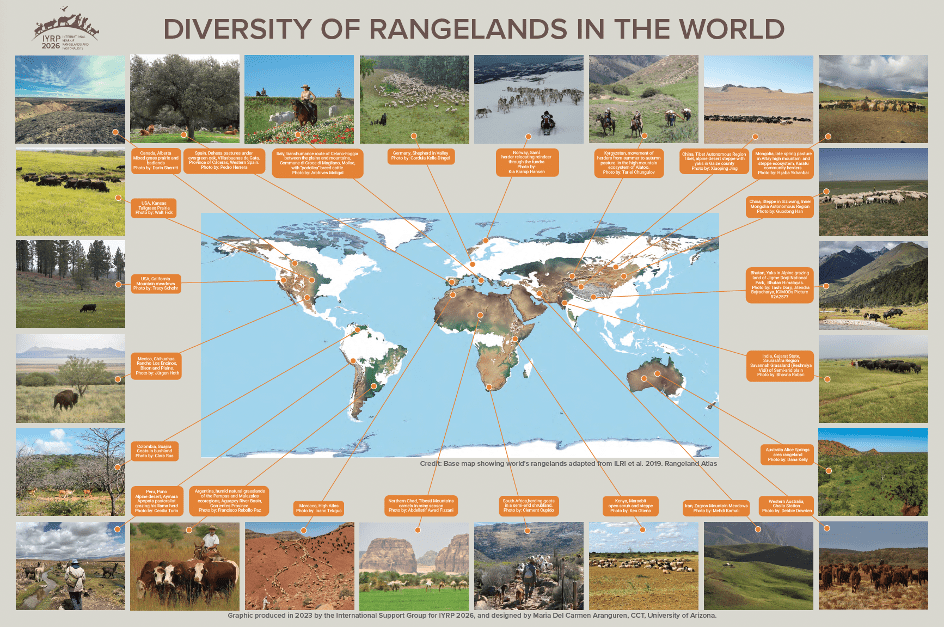

In the 2022 RWSN Webinar, Maryam Niamir-Fuller, then vice chair of the International Support Group for the IYRP2026, explained that “rangelands” is a term used for grasslands, shrublands, woodlands, tundra as well as cold or hot deserts that are grazed by domesticated or wild animals. I was surprised to learn that it is estimated that rangelands actually cover 54% of the earth’s land surface. It makes me wonder why I have heard so little about them? And further, rangelands exist beyond drylands. As Maryam gives you a taste for in her picture gallery (Figure 1), there is much diversity in rangelands.

Figure 1 Picture gallery of rangelands (prepared by IYRP2026 Global Alliance)

It perturbed me to learn from Maryam that, although rangelands cover more than half of the earth’s land mass, they are the least known and valued ecosystem in the world. What also seems not to be widely known is that an estimated one billion people directly benefit from or have their livelihoods linked to rangelands. Further, another two million people benefit along the value chain, including processing products, gathering pharmaceuticals and making medicines.

There are other nuggets of information that I would like to share with you. For example:

- that pastoral milk and meat are very important sources of vital proteins that are not found in plants

- that pastoral livestock has high genetic diversity – in stark contrast to livestock on monocultural farming and industrial systems

- rangelands are extremely important for Planet Earth’s biodiversity

Maryam also explained that, while evidence is still emerging, research is showing that a well-managed pastoral system can be net carbon neutral or can ever sequester (store) carbon. That is something else that I would like to know more about on this journey. In summary, it seems that a lot is going on in rangelands, but this is not well known.

Let me move on to pastoral mobility (pun intended). As I mentioned above, this is not outmoded at all, despite prevailing attitudes. In the 2022 RWSN webinar, Maryam lucidly explained that mobility is a key factor in the stewardship of these ecosystems. Pastoralists have adapted to and managed natural variability through mobility of their animals.

According to many studies, and as presented by Maryam Niamir-Fuller, one of the main reasons for rangeland degradation is because not all pastoralists are able to exercise their required mobility. Traditional movement routes have been blocked, and some rangelands have been converted to be used for cropping. The result is that animals are being confined into smaller and smaller spaces. Scientists are learning that the more the livestock keep moving, the less the degradation and the better are the chances for maintaining healthy rangelands.

Figure 2 The provisional 12 themes of the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralism

These issues and others are recognised through the 12 themes of the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (IYRP2026). The issue of water (and my own specialism) is directly included in two themes of the IYRP:

- Theme 3 looks at access to services and resources for pastoralists – advocating for safe and accessible water for pastoralists and their animals.

- Theme 6 looks at water in the context of soils and land management – including waste management, the impact of droughts, aquifer recharge and watershed management.

However, water can be linked to all of the 12 themes of the IYRP – something that will be explored in the build-up to and during IYRP2026. The IYRP sets out to value the contribution of rangelands and pastoralists, break myths and influence informed, science-based policies throughout the world.

If you would like to find out more about IYRP2026, or even join the global or regional support groups or thematic working groups, check out this website or contact iyrp2026@gmail.com

Sources of information

RWSN (2022) Pastoralists and Water, Webinar, Rural Water Supply Network (RWSN).

IYRP LDN Working Group (2024) “Global Actions for Sustainable Rangelands and Pastoralism to achieve Land Degradation Neutrality: A Science-to-Policy Review with recommendations for the UNCCD Conference of Parties”. https://iyrp.info/

[1] Director, Ask for Water Ltd, Edinburgh, Scotland

[2] Senior Advisor to IYRP2026 Global Alliance, based in USA