by Dr Kerstin Danert (1), Dr Klas Sandström(2), Dr Aida Bargués Tobella (3) , Dr Malin Lundberg Ingemarsson (4), Chris Magero (5) and Adrian Cullis (6)

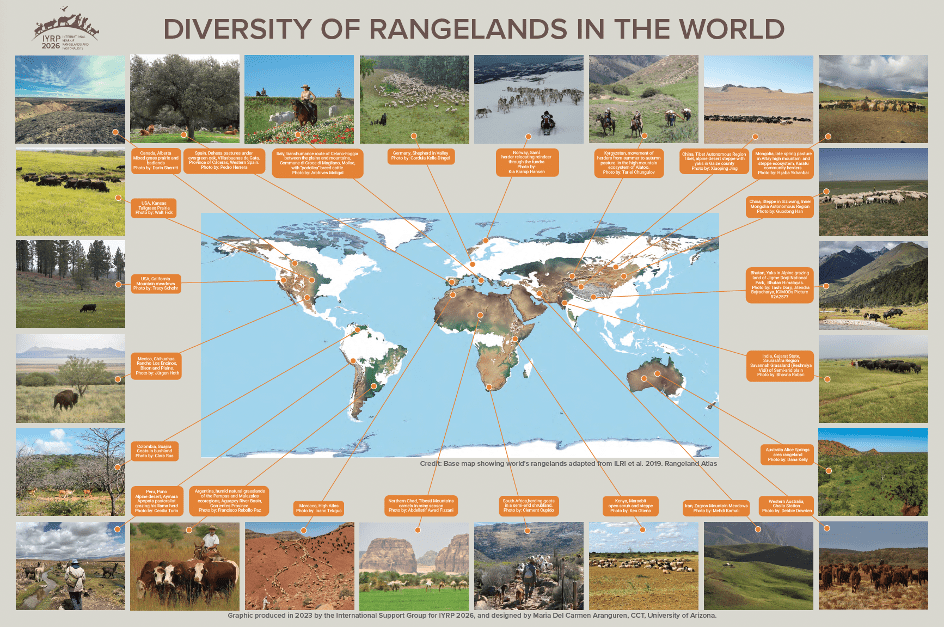

In support of the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (IYRP 2026) this is the fifth blog on Pastoralists and Water published through RWSN. We are going to provide you with a brief introduction to green water – a subject that is important when considering rangelands, pastoralism and pastoralists in many parts of the world (some may even argue everywhere). Before we move on, in case you have missed any of the other blogs on this topic, you can reach them here.

Some of us were given an opportunity to reflect and write on green water as members of the team preparing the 2023 Somalia Economic Update, entitled ‘Integrating Climate Change with Somalia’s Development: The Case for Water’ while others are researching this topic. In this blog, we don’t intend to summarise the report, which is in the public domain, but rather we want to help you understand, and perhaps think more about green water.

So, let’s get started – what on earth is green water? And why is it important? Ok, we shall get there via the term blue water.

Blue water

For many of us working on water supplies, water services, or irrigation, we make a living through the provision, or advice in relation to blue water. Blue water refers to the water that you see in rivers, lakes and dams, or that is abstracted from aquifers (groundwater). Blue water is what you see being used in irrigated agriculture or what livestock and humans drink. Generally, small amounts of blue water are required for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) needs and to water livestock. In contrast, irrigated agriculture (as well as some industry) uses larger quantities of blue water. Further, downstream users often benefit from upstream (blue water) runoff – which is not always aligned with the interests of the upstream communities!

Green water

In contrast, green water is water in soil. It accumulates there from rainfall (or other forms of precipitation) and subsequent infiltration. You can feel (and see) green water in how it makes soil damp or wet. Green water will either evaporate, be consumed by plants through the process of transpiration, or may percolate to recharge groundwater. Green water is what rainfed agriculture and rainfed ecosystems rely on. Pastoralists raise domesticated grazing animals – cattle, camelids, equines, sheep, goats, yaks, reindeer, pigs and even a variety of poultry (chickens, ducks and others). Rangeland vegetation, including grass, forbes, trees and shrubs, which are essential for this pastoral livestock all depend on green water.

Whether we are already familiar with the terms blue and green water or not, these definitions may not sound particularly exciting, but let’s continue. They link to a key aspect of many water scarce areas of the globe and how food and water security can improve.

Healthy soils: The key to green water replenishment

Water at the soil surface enters through a process called infiltration. Healthy soils have good physical, chemical and biological properties and therefore can absorb more water: they have what is known as a higher infiltration capacity.

In contrast, soil degradation results in surface compaction, crusting and sealing, which means less water can enter the soil, leading instead to surface runoff and an increased potential for erosion. This can also lead to agricultural, pastoral or ecological droughts: a deficiency of soil water that is not necessarily linked to a deficiency of rainfall (meteorological drought) but mostly to a poor soil health and infiltration capacity also known as hydrological functioning. It rains, but much of this rain never becomes essential green water.

However, agricultural, pastoral and ecological drought can actually be arrested and reversed through sustainable rangeland management and restoration. In other words, the replenishment of green water can be enhanced through practices that improve soil structure and through vegetative and structural measures that collect surface runoff and enable it to infiltrate. Half moons and a wide range of other rainwater harvesting structures are examples. More soil water supports plant growth, which in turn improves soil structure, enhances infiltration rates and results in improved hydrological functioning.

What about evaporation?

As we learned in the water cycle, water moves from the atmosphere to the ground, from mountains to the sea, across land, along rivers, underground and through pipes. These are flows that we can observe or measure.

Transpiration and evaporation return some precipitation to the atmosphere. Transpiration is linked to plant growth, but evaporation, which is vast and invisible arguably remains largely overlooked and is poorly managed. Locally, transpiration contributes to the production of food, fuel, and fodder. In contrast, evaporation does not contribute locally, bit will rather condense and become rainfall (or snow, hail, sleet or fog) elsewhere. Evaporation is very important, because on a farmer’s field or in a small catchment, much of the rainfall that reaches the ground can evaporate.

Reducing evaporation and harnessing more rainfall for productive transpiration may not be easy, but well-established knowledge about it does exist. Effective land management will capture rainwater, promote infiltration, reduce evaporation, thus providing more green water, which still returns to the atmosphere as plant transpiration. That lead us to our next point.

Rangeland management – the key to more water for food, fuel, fodder and services

Rangeland management controls two critical hydrological processes – infiltration and evaporation. It also controls the extent that rainfall is converted into green water and hence is available for transpiration (i.e. for food, fuel and fodder).

When landscapes and watersheds are better managed, they more effectively catch rainfall, reduce and control runoff, and enable water to infiltrate the soil. This enables soil to absorb more rainfall and increase levels of green water, contributing to the productivity of grasses, shrubs, trees and crops and reducing evaporation. More green water can support more livestock, crops and forests with reduced ecological damage, ultimately contributing to healthier communities and stronger local economies.

Why does green water matter for blue water?

Better rangeland management, including using rainfall in upstream areas and promoting rainfed agriculture (including pastoral livestock), generates and harnesses more green water. This can enable savings to be made on blue water, which can therefore be used more productively for domestic use, watering livestock and even for high-value (export) crops.

| A planetary boundary for freshwater that includes green water Let’s put green water in a larger context. In 2009, Johan Rockström and Stockholm Resilience Centre published the Planetary Boundaries (PBs) concept, presenting a set of nine planetary boundaries which are essential for present and future humanity to develop and thrive. One of the original boundaries is “freshwater use”. In 2022, they published a study on a planetary boundary for green water in which they explain how green water links the freshwater boundary to other planetary boundaries such as land use, biodiversity and climate. Based on global changes to soil moisture, the study concludes that the green water planetary boundary has already been transgressed – highlighting the urgency in giving more attention to this aspect within the hydrological cycle. |

The earlier mentioned 2023 Somalia Economic Update report is not only relevant for Somalia, but for other dryland countries whose economic and human well-being depends on how their water resources are managed. We argue that a critical entry point in such contexts is recognising the role of evaporation—the often overlooked, invisible flow of water, which could be better harnessed to support food and water security, and which is closely linked to both green and blue water resources. What do you think

Let us stop here for now. We hope that some of you may share your thoughts, and we look forward to hearing your reflections as this blog series on pastoralists and water continues.

- Ask for Water Ltd, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- Independent Consultant, Sweden

- AGROTECNIO-CERCA Center, Lleida, Spain

- Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI), Stockholm, Sweden

- Independent Consultant, Germany

- Independent Consultant, United Kingdom