Il s’agit du troisième d’une série de quatre blogs intitulée ‘Le forage professionnel de puits d’eau: Apprendre de l’Ouganda” de Elisabeth Liddle et d’un webinaire en 2019 sur le forage de puits professionnel. Cette série s’appuie sur les recherches menées en Ouganda par Liddle et Fenner (2018). Nous vous invitons à nous faire part de vos commentaires en réponse à ce blog ci-dessous.

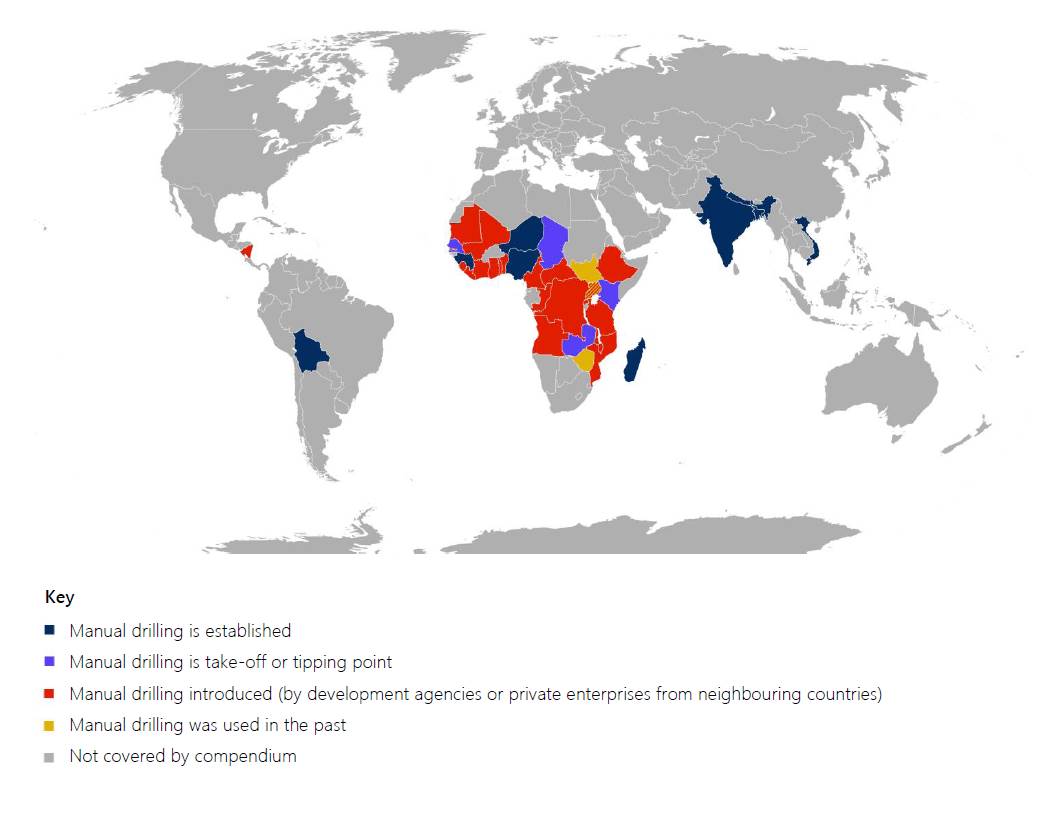

Plusieurs rapports récents ont remis en question la qualité des forages en cours de construction en Afrique subsaharienne rurale (UNICEF/Skat, 2016, Bonsor et al., 2015; Anscombe, 2011; Sloots, 2010). Pour implanter et construire des forages de haute qualité être, un personnel qualifié et expérimenté doit être en mesure d’effectuer ces travaux. Des recherches récentes en Ouganda montrent qu’un certain nombre de consultants et d’entrepreneurs en forage parmi les plus expérimentés en Ouganda (ceux qui sont en activité depuis quinze à vingt ans) ne sont plus disposés à être engagés pour des contrats de collectivités locales de district (Liddle and Fenner, 2018). Ceci est préoccupant, étant donné que les projets des collectivités locales de district représentent 68% des nouveaux forages profonds forés au cours de l’année fiscale 2016/17 (MWE, 2017).

Dans ce blog, j’explique pourquoi ces consultants et entrepreneurs en forage ne sont plus disposés à travailler pour les districts.

1. Les prix sont trop bas

Un certain nombre de consultants et d’entrepreneurs de forage interrogés ne sont tout simplement pas satisfaits des prix que les collectivités locales de district sont prêtes à payer par rapport aux organisations non gouvernementales (ONG). Les consultants interrogés, par exemple, ont déclaré que les districts sont généralement disposés à payer de 1 à 2 million d’UGX (276 $US – 552 $US [1]) pour l’implantation et la supervision, tandis que les ONG sont généralement disposées à payer de 2,5 à 3,5 millions d’UGX (691 $US – 967 $US) pour le même travail. Le prix que les districts sont prêts à payer n’est apparemment pas réaliste et, en conséquent, ces consultants ne seraient pas en mesure de réaliser un travail de qualité. Les mêmes problèmes ont été signalés chez les foreurs qui ne sont plus disposés à travailler pour les autorités locales du district. Ces consultants et foreurs ne sont pas prêts à réaliser des points d’eau inférieurs aux normes pour les communautés du fait de ces bas prix, à prendre des raccourcis dans leur travail, ou à ternir la réputation de leurs entreprises.

2. Usage abusif des modalités de paiement forfaitaire “pas d’eau, pas de paiement”

Comme l’explique le blog “Contrats clés en main pour l’implantation et le forage de puits d’eau“, l’utilisation de contrats clés en main est fréquente en Ouganda: sur les 29 organisations interviewées au cours de cette recherche, 26 organisations travaillaient avec le secteur privé dans le cadre de contrat de forages, et 19 rémunéraient les foreurs pour l’implantation et le forage à travers des paiements forfaitaires “pas d’eau, pas de paiement”. Il est typique selon ces modalités de paiement que le foreur ne soit pas payé, si un forage échoue (si il est à sec ou à faible rendement). Si le forage est réussi, le foreur doit recevoir le prix forfaitaire total, quels que soient les coûts engagés sur place. Un certain nombre de districts, cependant, s’écartent des normes de paiement forfaitaire “pas d’eau, pas de paiement”. Au lieu de payer la totalité de la somme forfaitaire comme ils devraient le faire, ils ne paient que pour le travail réellement effectué et les matériaux utilisés (connu sous le nom de paiement au devis (BoQ) ou paiement ‘admeasurement’ en Ouganda). Bien que cela puisse être spécifié dans le contrat de forage, cela reste inquiétant, étant donné la prémisse sur laquelle les modalités de paiement forfaitaire “pas d’eau, pas de paiement” est basée: même si les foreurs perdent de l’argent sur les forages infructueux, ils devraient être en mesure de récupérer ces coûts à travers les sommes forfaitaires qui leur sont versées pour les forages réussis. Sans un paiement forfaitaire intégral, les foreurs sont incapables de recouvrir leurs pertes.

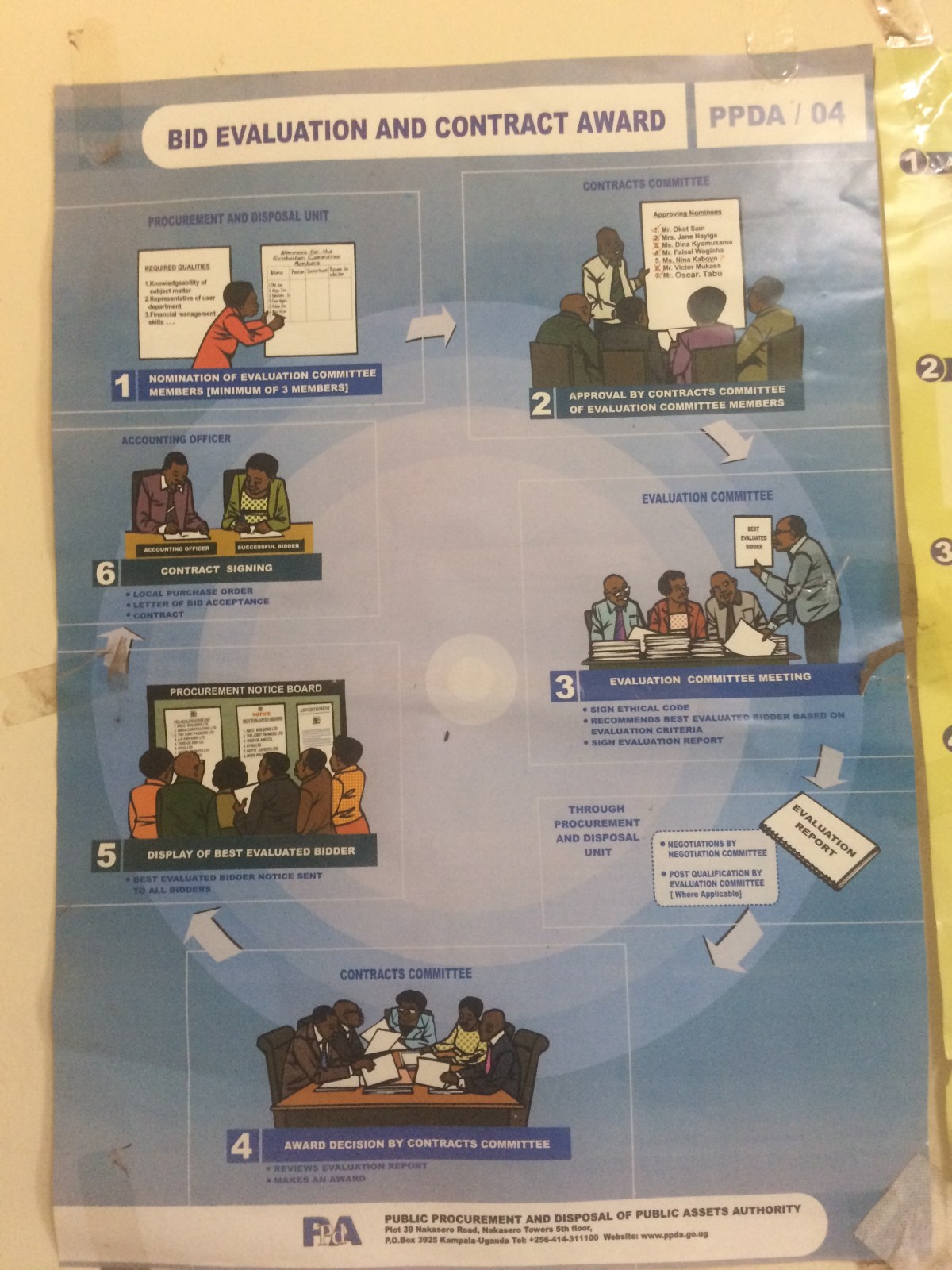

3. Les pots-de-vin pendant le processus d’appel d’offres

Les demandes de pots-de-vin seraient fréquentes lors des appels d’offres pour des contrats de collectivités locales de district. Lorsqu’un pot-de-vin est exigé, les consultants et les foreurs ont du mal à rendre compte de ce coût : s’ils en tiennent compte dans leur devis, leur devis sera trop élevé et ils ne gagneront donc pas le contrat. Si, toutefois, ils ne tiennent pas compte du prix du pot-de-vin dans leur devis, le consultant ou le foreur devra alors récupérer ce coût à un moment donné, généralement en effectuant un travail de mauvaise qualité sur place. Si les consultants et les foreurs ne veulent pas travailler dans ces conditions, ils ne soumissionneront pas.

4. Les retards de paiement

Recevoir un paiement intégral de la part des districts pour les travaux achevés peut être difficile: plusieurs entrepreneurs de forage signalent que dans certains cas, ils ont dû attendre plus d’un an pour recevoir leur paiement intégral. Cela rend les affaires difficiles. Il est beaucoup plus facile de ne travailler que pour des ONG qui ont la réputation de payer à temps.

Les citations suivantes aident à illustrer les problèmes ci-dessus:

«Mais je vous le dis, ces dernières années, je n’ai pas soumissionné pour un contrat avec le district, car le processus de candidature est tellement ridicule. Vous savez, ils savent déjà qui va remporter le contrat avant même de l’annoncer … Et les termes et conditions du contrat sont très défavorables au foreur … Je n’ai donc pas foré pour le district depuis cinq ans, rien ne garantit qu’ils nous paieront, ce n’est pas un modèle commercial viable pour nous… Ils paient seulement à temps dans 50% des cas. Même si le forage a réussi, ils diront: Nous n’avons pas d’argent, nous devrons payer le prochain trimestre. Parfois, cela dure depuis un an. Avec un district, il a fallu 14 mois pour que je sois payé une fois… La garantie de recevoir un paiement est frustrante» (Entrepreneur de forage).

«Je crois fermement que la passation de marché est seulement une procédure pour la plupart des projets. Dans la plupart des cas, les districts signent des contrats après que le soumissionnaire leur ait donné de l’argent pour celui-ci. Alors, disons que c’est un contrat de 100 millions, ils voudront 20 millions lors du processus d’appel d’offres. Ce problème concerne les districts, pas les ONG, ni le ministère … J’ai donc arrêté de forer pour les districts, c’était trop cher» (Entrepreneur de forage)

«Je n’aime pas travailler pour le district. Pour être honnête, ils sont tout simplement corrompus. Il est très difficile d’obtenir un contrat de leur part, vous devez souvent payer pour obtenir le contrat. Ils demanderont toujours de l’argent en plus. C’est dérangeant. Si vous n’acceptez pas de les payer, ils trouveront un moyen d’expliquer pourquoi vous n’avez pas obtenu le contrat » (Consultant)

Les districts commencent maintenant à remarquer ce problème également, comme l’explique l’un des responsables de l’eau du district ci-dessous:

«Un si grand nombre d’entre eux [les foreurs] ont une mentalité tellement axée sur le “business” que pendant la période de la passation de marché, ils montent une offre qui défie toute concurrence avec des prix trop bas afin de pouvoir remporter le contrat. La plupart des foreurs sérieux travaillent maintenant seulement avec les ONG car ils savent que le processus de passation de marché est beaucoup plus transparent et qu’ils pourront obtenir l’argent dont ils ont besoin pour faire du bon travail. Mais avec le gouvernement local, ils ne peuvent pas. Nous avons donc perdu de très bons foreurs à cause de cela, parce qu’ils ne peuvent pas défier cette concurrence, et que la plupart des gouvernements locaux veulent choisir le soumissionnaire aux prix les plus bas… Nous avons donc un gros défi à relever car nous ne voulons pas que le gouvernement perde de l’argent en sélectionnant les foreurs les plus chers mais cela signifie que les foreurs qui font du travail de très haute qualité ne travaillent plus avec le district » (Responsable de l’eau pour le district)

Ces citations mettent en évidence les conséquences à long terme pour les administrations locales de district connues pour des pratiques telles que payer des prix trop bas, proposer des conditions de paiement défavorables, solliciter des pots-de-vin et effectuer des paiements en retard. Il est essentiel de trouver des solutions à ces problèmes pour que des consultants expérimentés et des entrepreneurs en forage soient prêts à soutenir les travaux des districts.

Qu’en pensez-vous?

Alors, qu’en pensez-vous? Avez-vous des expériences de prix bas irréalistes (ou l’inverse), de conditions de paiement défavorables, de corruption dans le processus de passation de marché ou de retards de paiement? Ou pouvez-vous partager des pratiques particulièrement prometteuses avec nous? Vous pouvez répondre ci-dessous en postant un commentaire, ou vous pouvez participer au webinaire en direct le 14 mai (inscriptions ici)

Références

Anscombe, J.R. (2011). Quality assurance of UNICEF drilling programmes for boreholes in Malawi. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Agriculture Irrigation and Water Development, Government of Malawi, Available from http://www.rural-water-supply.net/en/resources/details/509

Bonsor, H.C., Oates, N., Chilton, P.J., Carter, R.C., Casey, V., MacDonald, A.M., Etti, B., Nekesa, J., Musinguzi, F., Okubal, P., Alupo, G., Calow, R., Wilson, P., Tumuntungire, M., and Bennie, M. (2015). A Hidden Crisis: Strengthening the evidence base on the current failure of rural groundwater supplies, 38th WEDC International Conference, Loughborough University, UK, 2014, Available from https://wedc-knowledge.lboro.ac.uk/resources/conference/38/Bonsor-2181.pdf

Liddle, E.S. and Fenner, R.A. (2018). Review of handpump-borehole implementation in Uganda. Nottingham, UK: BGS (OR/18/002). https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/520591/

MWE (2017) Sector Performance Report 2017, Ministry of Water and Environment, Government of Uganda, Available from https://www.mwe.go.ug/sites/default/files/library/SPR%202017%20Final.pdf

Sloots, R. (2010). Assessment of groundwater investigations and borehole drilling capacity in Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Water and Environment, Government of Uganda, and UNICEF, Available from http://www.rural-water-supply.net/en/resources/details/133

UNICEF/Skat (2016). Professional water well drilling: A UNICEF guidance note. St Gallen, Switzerland: Skat and UNICEF, Available from http://www.rural-water-supply.net/en/resources/details/775

[1] taux de change de Mai 2017

Remerciements

Ce travail fait partie du projet Hidden Crisis du programme de recherche UPGro – cofinancé par le NERC, le DFID et l’ESRC.

Le travail de terrain entrepris pour ce rapport fait partie de la recherche doctorale des auteurs à l’Université de Cambridge, sous la supervision du Professeur Richard Fenner. Ce travail sur le terrain a été financé par le Ryoichi Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship Fund et UPGro : Hidden Crisis.

Merci à ceux d’entre vous de l’Université de Makerere et de WaterAid Ouganda qui m’ont apporté un soutien logistique, y compris sur le terrain, pendant que je menais les entretiens pour ce rapport (en particulier le Dr Michael Owor, Felece Katusiime et Joseph Okullo de l’Université Makerere et Gloria Berochan de WaterAid Uganda). Merci également à tous les répondants d’avoir été enthousiastes et disposés à participer à cette recherche.

Photos

photo: ” Affiche d’évaluation des offres et d’attribution du contrat exposée dans un bureau de passation de marché de district ” (Source: Elisabeth Liddle)

Guest Blog by GIFT JASON WANANGWA

Guest Blog by GIFT JASON WANANGWA

Course modules

Course modules