Photograph 1 Showing a Graduate in Kenya, Source: NTV Kenya

Blog by Euphresia Luseka, co-lead of the RWSN Leave No-one Behind theme.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Rural Water Supply Network (RWSN) or its Executive Committee.

Fake Qualifications, Real Consequences: The Brenda Sulungai Case

Across Africa, water utilities are expected to be drivers of sustainable development, climate resilience, and digital transformation. Yet beneath this ambition lies a disturbing contradiction: highly complex systems are being operated by staff who, in most cases, lack even the basic credentials to do the job.

Despite major gains in infrastructure and technology investments, Kenya’s water utilities continue to underperform often not due to a lack of funding or innovation, but because of the human capital crisis festering within. I have witnessed strategic plans, technological upgrades, and donor-funded initiatives collapse under the weight of a talent base that was never prepared or licensed.

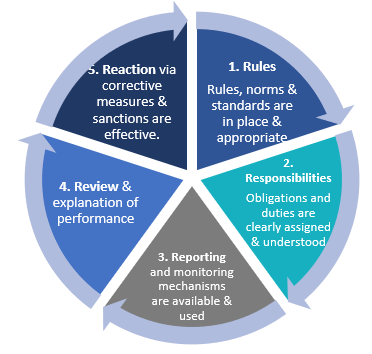

In July 2025, Brenda Nelly Sulungai a former staff at Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company (NCWSC), was arraigned in a Kenyan Court, for forgery, uttering a false document, and deceiving a principal to gain employment. The Sulungai case demonstrates that the underlying problem extends far beyond individual misconduct on fraudulent activities, but rather the existing system permits such deception to occur and persist undetected for long. A fundamental breakdown exists in the accountability mechanisms embedded within the Human resources ecosystem of Water Corporations and Utilities.

This blog analyses the technical, legal and operational risks posed by weak certification systems, forgery, and unqualified staffing across Kenya’s water sector. It also proposes a plan for professionalising the sector, building institutional resilience, and restoring public’s vital trust.

The Pervasive Scale of Credential Fraud

“Every academic certificate in Kenya is now questionable. Forgery is happening across all sectors including those critical to life like water and health. We cannot ignore this anymore.” –Twalib Mbarak, CEO, Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC)

This stark statement captures the magnitude of Kenya’s credential fraud crisis as a structural failure that compromises public service integrity at scale as demonstrated in Box 1.

| Box 1: Sector-Wide Credential Fraud Uncovered in National Audit Following a 2022 presidential directive, the Kenya National Qualifications Authority (KNQA), in collaboration with the EACC and the Public Service Commission (PSC), audited academic and professional credentials across 400+ public institutions. Of 47,000 employment records reviewed, over 10,000 (30%) were forged or unverifiable documents. Credential fraud in Water Service Providers (WSPs) flourished under conditions of decentralised recruitment, limited HR oversight, and politicised hiring. Frontline operational roles such as meter readers, plant technicians, lab staff, and revenue officers are especially vulnerable to infiltration by individuals presenting forged or non-accredited certificates. In a coastal county, 5 out of 8; 63% of water treatment technicians lacked formal technical certification highlighting serious lapses in frontline hiring. WSPs such as Nairobi City and Garissa Water & Sewerage Company were cited for fraudulent promotions and appointments. The audit prompted a directive requiring all WSPs to submit comprehensive staff verification reports. EACC investigated over 2,000 public servants for holding fraudulent academic qualifications. In parallel, PSC has flagged more than 1,200 employees with irregular documentation in public institutions, signalling collapse in credential verification and HR governance. |

“This is systemic. There are falsified documents even at PhD level, dissertations are downloaded from the internet.” – Dr. David Oginde, Chairperson, EACC

Senior public officials have not minced words. Head of Public Service Felix Koskei has declared the forged qualifications surge a ‘national emergency.’ PSC Chairman, Anthony Muchiri emphasised the urgency of cultural reform, framing the restoration of integrity as both a legal and moral imperative.

Consequently, this is not simply a matter of individual misconduct it points to a systemic failure in verification systems, risk management, and institutional accountability.

The Grave Consequences: Incompetence Endangering Lives and Undermining Progress

The human capital crisis in Kenya’s water sector driven by systemic weaknesses in credential verification, licensing, and staff training is not only an administrative oversight but threatens public health and utility performance.

Improper chlorine dosing, no action on bacteriological alerts and contaminated boreholes link to unqualified personnel, contributing to recurrent outbreaks of waterborne diseases such as cholera and typhoid. Therefore, Water sector HR reforms must be framed not just as a governance issue, but as a public health and national security imperative.

“You cannot digitize your way out of poor staffing. At some point, someone has to operate the system.”

The human resource crisis is also undermining the operational stability and financial viability of Kenya’s WSPs. Underqualified technical staff routinely mismanage complex systems like SCADA and GIS, leading to frequent breakdowns and service disruptions. Poorly trained revenue officers contribute to billing errors, customer dissatisfaction, and 30% revenue leakage crippling reinvestment in maintenance and training. Even as utilities embrace digitisation, adoption is hindered by a lack of skills and internal resistance to change. Without parallel investment in the human capabilities needed to run and sustain infrastructure, digital and capital investments risk failing to deliver impact.

Sustainable transformation requires human capital to be treated as a core infrastructure asset.

Systemic Vulnerabilities and Their Underlying Causes

I. Governance Deficit: Institutional Decay Through Political Capture

Kenya’s water sector suffers from a foundational governance breakdown; WASREB, the national water regulator notes a few WSPs have structured HR policies, indicating systemic weakness. Other gaps include: Outdated job descriptions, Irregular or absent performance reviews and Non-existent competency frameworks.

“Staff appointments in WSPs are frequently driven by tenure, local allegiances, or political alignment rather than technical merit. This erosion of meritocracy is neither incidental nor benign; it is indicative of deliberate political capture.”— Charles Chitechi, President, Water Sector Workers Association of Kenya (WASWAK)

Even WSP BODs that are governance bulwarks, are compromised. Opaque recruitment, undertrained members, and entrenched conflicts of interest have rendered them susceptible to patronage.

This politicisation has real operational costs, including poor service delivery, stagnant capacity, and a rise in credential forgery.

II. Regulatory Void: Absence of Mandatory Professional Licensing

Despite being designated as Kenya’s 16 critical infrastructure sectors, the water sector lacks a national mandatory licensing framework. Unlike medicine or engineering, no statutory barrier prevents an unqualified person from operating a treatment plant. Training institutions exist, including KEWI, NITA, and TVETs, but certification is inconsistent, and unenforced. Most alarming is the absence of a centralised professional registry, allowing forgeries to pass undetected unless exposed by whistleblowers.

Kenya’s current policy approach enables fraud by omission. The lack of a licensing regime is not a gap; it is a deliberate vulnerability.

III. Investment Blind Spot: Human Capital as the Missing Infrastructure

According to WASREB, Kenya’s WSPs spend less than 1% of OPEX on staff training, compared to the 5%-7% benchmark in high-performing WSPs globally. This chronic underinvestment in people creates a compounding deficit: Stagnant skills lead to operational bottlenecks, Low morale drives attrition and disengagement and Poor efficiency increases non-revenue water (NRW).

“You cannot digitize your way out of poor staffing. At some point, someone has to operate the system.”

A study by AfDB found that targeted training investment can lead to 20%-30% efficiency gains. The false economy of skipping training leads to far greater costs through system failures and revenue loss.

These figures make the business case clear. Training is not a cost; it is a strategic investment with measurable returns.

IV. Project Design Fallacy: Infrastructure Without Operators

Despite significant investments in tools such as GIS mapping, NRW audit software, and digital billing systems, Kenya’s utilities remain trapped in underperformance.

From experience, the primary reason infrastructure projects fail is they’re often designed for a workforce that does not yet exist. Few pause to ask: Who will operate, manage, and sustain these systems?

This leads to predictable implementation failures. Development partners often assume that technology adoption is a standalone solution, overlooking the critical human capability gap.

Table 1 Showing Summary of Systemic Failures and Strategic Fixes

| Root Problem | Underlying Cause | Strategic Fix |

| Politicized HR and opaque recruitment | Governance failure | Independent oversight and merit-based systems |

| Weak mandatory licensing | Regulatory neglect | National framework aligned with global standards |

| Minimal training investment | Financial and strategic myopia | Mandated 5% OPEX for staff development |

| Failed technology implementations | Ignored human capacity gap | Capacity-first planning and project sequencing |

Towards Resilience: Five Strategic Levers to Professionalize Kenya’s Water Sector

Kenya’s water sector is confronting a systemic talent crisis, addressing these challenges requires a structural response anchored in global best practices, informed by local constraints, and focused on long-term institutional resilience. This plan outlines 4 interlocking strategic levers designed to professionalize the sector and establish talent as a core infrastructure asset.

| Lever | Core Insight | Priority Actions | Strategic Shift | Expected Outcome |

| Proactive Credential Verification | Shift from post-hire audits to real-time identity checks | Integrate KNQA/KUCCPS into hiring- Enforce role-based access protocols. Adopt zero-trust frameworks | Link credential verification to hiring and promotions | Pre-employment fraud prevention; increased hiring integrity |

| Mandatory Licensing for Technical Roles | Legalise role-based licensing to ensure competence | Establish national licensing board- Align with NQFs- Phase rollout starting with public-facing roles | Make licensing a prerequisite for key technical roles | Professionalised, accountable workforce |

| Performance-Driven HR Governance | Replace tenure-based hiring with performance-linked systems | Implement HR scorecards tied to KPIs- Map skills to close gaps- Link career progression to performance | Institutionalise meritocracy and depoliticise HR | Talent aligned with service outcomes; improved retention |

| Strategic Learning Investment | Treat training as core infrastructure, not a cost centre | Mandate 5% OPEX for learning- Deploy centralized Learning Management System- Align training to operational KPIs | Make capacity-building part of financial and project planning | Technically agile, continuously upskilled workforce |

Conclusion: Talent Is Infrastructure

Kenya’s water systems are only as effective as the people who plan, operate, and maintain them. As the World Bank warns, weak water institutions can turn climate risks into crises undermining resilience across health, agriculture, and energy systems.

The Brenda Nelly Sulungai case shows credential fraud is not just a governance lapse it’s a national risk multiplier. Amid climate stress and population growth, human error becomes infrastructure failure.

Reform must begin and end with people. Priority actions include:

- Verifying identities and qualifications through real-time credential checks

- Mandating professional licensing to close technical regulatory gaps

- Investing in structured, ongoing training

- Aligning performance systems with merit-based progression

- Fostering a culture of accountability, technical rigor, and service

These steps reflect a central truth: talent is infrastructure.

Former President Mwai Kibaki, UNESCO’s Special Envoy for Water in Africa, put it clearly: “We need to commit ourselves to turning actions into real reforms… and together we can make Africa water secure and peaceful.”