Handpumps have revolutionized access to safe and reliable water supplies in Sub-Saharan African countries, particularly in rural areas. They constitute a healthy and viable alternative solution when surface water is contaminated. Danert (2022) estimates that 200 million people in sub-Saharan depend on 700,000 handpumps to supply themselves with drinking water.

Unfortunately, many handpumps service face performance issues or premature failure due to technical or installation defects in the borehole or pump, operational and maintenance weaknesses, or financial constraints (World Bank, 2024). Statistics on the functionality of handpumps in Cameroon are very sparse and dispersed with very little data available. However, some studies show that 25% to 32% of handpumps in Cameroon are inoperative (RWSN, 2009; Foster et al., 2019).

Previous reviews of handpumps functionality data in Cameroon have been conducted, including RWSN (2009) and Foster et al. (2019). However, these estimations were based on partial data and thus may not reflect the situation in the country as a whole. In addition, the number of handpumps installed each year is constantly increasing, and there is a need to update functionality data. Thus the interest of the study.

The methodological approach used in this study was based on online searches. To do so, we searched, collected, and analyzed relevant data from the 310 Councils Development Plan (CDP) that had been collected from 2010 to 2022. Information sources included data sets and documents available online through the data portals of the National Community-Driven Development Program (PNDP).

Overall, based on the data analysed, the number of handpumps used as the main source of drinking water supply in Cameroon is 20,572, of which 9,113 are installed in modern wells and 11,459 in boreholes. Approximately 8.2 million people in Cameroon rely on a handpump for their main drinking water supply, which is equivalent to 36.8% of the population of Cameroon. Findings indicates that one in three handpumps in Cameroon is non-functional, which in 2022 was roughly equivalent to 6,724 inoperative water points. To put this in perspective, this number is about 33% of the total number of handpumps, enough to supply 2.7 million people, assuming 400 inhabitants per handpumps. According to this estimate, it is about 44.8 billion CFA francs, or 66.8 million USD, was invested in the construction of water points that are immobilized and do not generate any benefit (improved health, nutrition, or education).

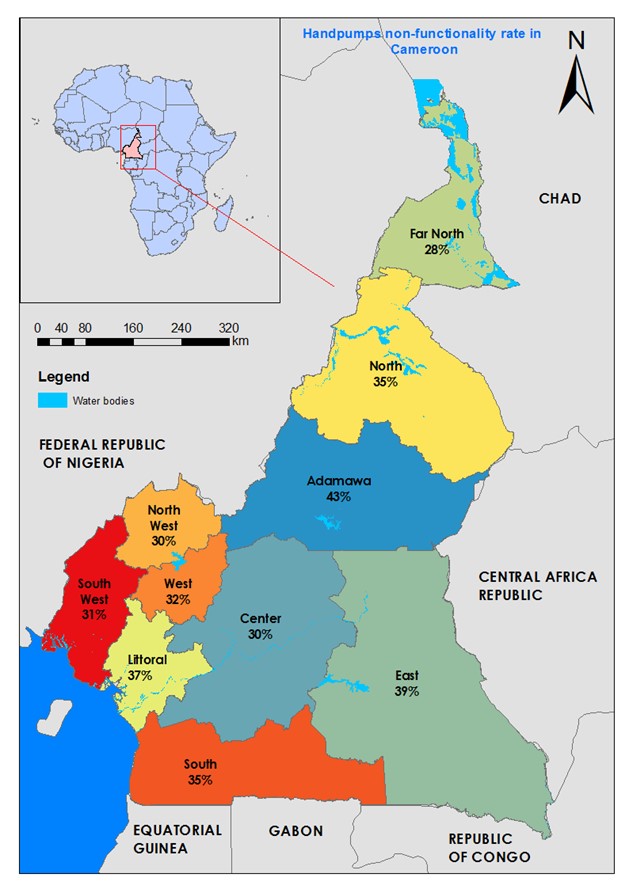

Figure 1 presents estimations of non-functionality in the ten regions of Cameroon. This figure shows that the region that had the highest level of non-functional handpumps is the Adamawa region (43%), followed by the East region (39%), the Littoral (37%), the North (35%), the South (35%), the West (32%), the South West (31%), the Center (30%), the North West (30%), and the Far North (28%).

The handpumps, like the Community Based Management, seem not to have given the expected results. The fact that some handpumps fail prematurely seems to indicate that technical defects (poor quality components and rapid corrosion) contribute to handpump failure and underperformance. Further, this review notes that questions related to the quality of handpump material and the corrosion of handpumps have not been sufficiently taken into account in the various research studies in Cameroon and Sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, Future research should focus on physical audits of handpumps, and handpump rehabilitation campaigns in order to shed light on these issues. Finally, preventing rapid corrosion of handpumps through regulations should be implemented in order to improve the performance of handpumps. Regulations may be implemented at the national, regional, or local levels, and it is advised to employ a pH threshold of less than 6.5 as a corrosion risk indication. Once they are more precisely defined, additional risk factors such as salinity, chloride, and sulphate levels can be added.

About the author:

Victor Dang Mvongo, MSc is a PhD Student at the University of Dschang (Cameroon) and an independent consultant in WASH. He conducted the work featured in this blog at the Faculty of Agronomy and Agricultural Sciences.

Further reading:

Mvongo D.V, Defo C (2024) Functionality of water supply handpumps in Cameroon (Central Africa). Journal of water, sanitation and Hygiene for development. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2024.085

References:

Danert, K. (2022) Halte aux dégradations Rapport I : Fiabilité, fonctionnalité et défaillance technique des pompes à motricité humaine. Recherche-action sur la corrosion et la qualité des composants des pompes à motricité humaine en Afrique subsaharienne. Ask for Water GmbH, Skat Foundation et RWSN, St Gallen, Suisse.

Foster, T., Furey, S., Banks, B. & Willets, J. 2019 Functionality of handpump water supplies: a review of data from sub-Saharan Africa and the Asia-Pacific region. International Journal of Water Resources Development 36 (5): 855–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2018.1543117

RWSN 2009 Handpump data, selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa. RWSN, St Gallen, Suisse. https://www.ruralwater-supply.net/_ressources/documents/default/203.pdf