The e-discussion on the topic of “Cost effective ways to leave no-one behind in rural water and sanitation” has come to an end and we are very grateful for the 40+ participants who actively took part. A summary of the e-discussion can be found here. Additionaly, we as moderators want to share our own summary of the discussion in this short blog.

Authors: Julia Boulenouar, Louisa Gosling, Guy Hutton, Sandra Fürst, Meleesa Naughton.

As duty bearers for the realisation of human rights to safe drinking water, States have the responsibility to ensure that no-one is left behind. And the SDG framework clearly sets out the need for all stakeholders to work together on the challenge. This e-discussion was an opportunity for diverse members of the Rural Water Supply Network to share lessons and views on how this can be done.

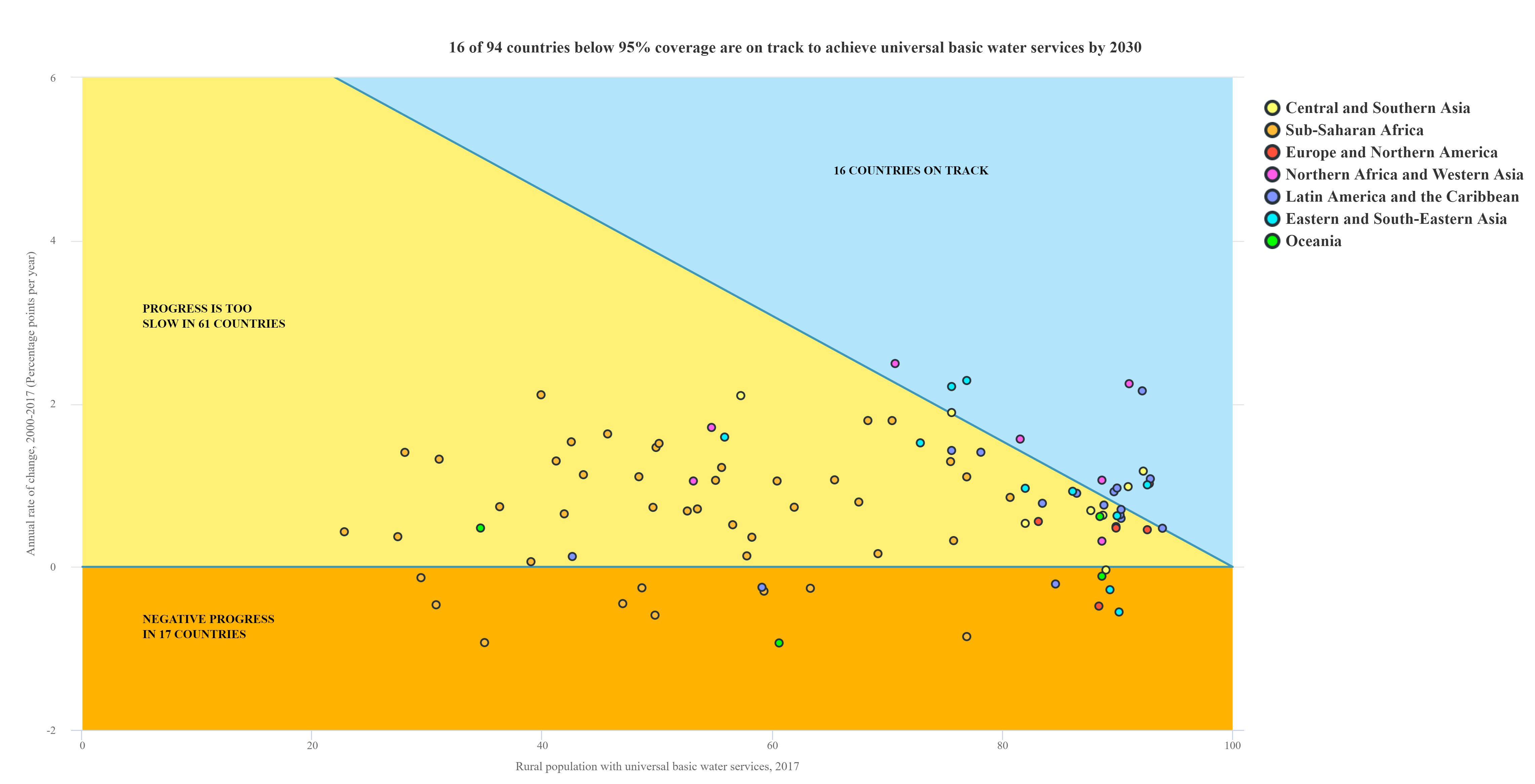

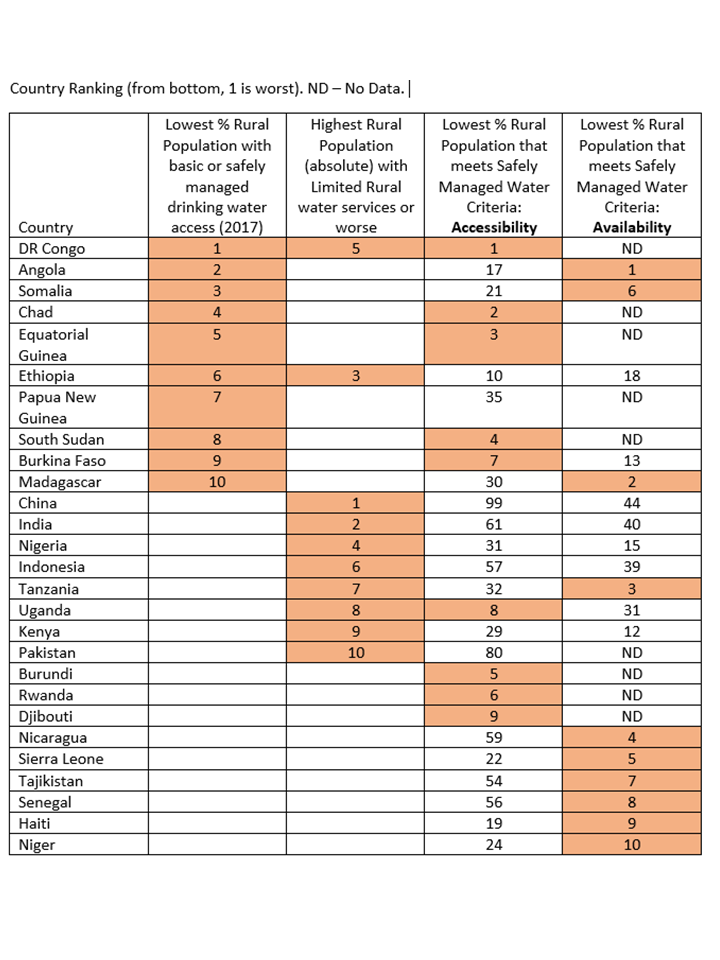

Reminding ourselves of the challenge at stake: since the SDG WASH targets 6.1 and 6.2 were adopted in 2015, the sector has been thinking hard about how to finance the ambitious goal of providing access to safely managed WASH services for everyone, everywhere and forever. This ambition is even more challenging in rural areas, where coverage levels are lower and the unserved include remote communities which are harder to reach and often poorer.

In order to develop a credible financial strategy to achieve this ambition and leverage resources, governments and sector stakeholders need to determine the real costs involved (not only to provide first time access for a few, but sustainable services for all) and the sources of funding that are available and can be mobilised. It needs credible data on those aspects as well as on the population served and unserved, including the most vulnerable groups.

What we already know about the cost of providing WASH services: the costs of providing services rely on many factors and the WASH Cost initiative led by IRC has helped to identify 6 categories beyond capital expenditure to include among others, operation and maintenance, capital maintenance expenditure and direct support. We know that some of these cost categories are largely unknown and as a result, not planned, not budgeted and not financed. This is the case for capital maintenance expenditure and for direct support costs (generally referring to costs for local government to support service providers).

In terms of actual costs, a World Bank study of 2016 showed that $114 billion per year would be needed globally to cover capital costs and roughly the same for operation and maintenance.

What we know less about is the real cost of providing services to all, especially for those left behind (including those marginalised and those discriminated against) and this is because limited data are available. We also recognise that beyond the 6 generic cost categories, many costs are unknown and neglected and these include:

- the non-financial time costs of WASH access,

- the cost of taking time to properly understand demand, recognising gender differences and diverse perspectives,

- the cost of strengthening skills and stakeholder capacity to fulfil their mandate, particularly service authorities and service providers,

- the cost of corruption,

- the time and cost of including people with disabilities and others who are socially excluded in services.

These can be seen as cost drivers rather than additional categories, but should be thought through, every time services are planned for.

Who is currently financing this goal and who should do more? Leaving no one behind is the responsibility of national governments. They need to mobilise funding through a combination of sources, including government (taxes), development partners (transfers) and users (tariffs). This is usually known as the “3Ts”. In some contexts, the private sector may have a role to play in investing in water services. However, results from countries that conducted to identify and track WASH financing with the UN-Water tool TrackFin, show that the main contributors for the sector are by far the users who are paying for their own services through capital investment (Self-supply) and through water tariffs (operation and maintenance). In that context, should we consider revising the “3Ts” to “3Ts and S” to acknowledge the importance of Self-supply in the mix of services? And should we also add a 4th T for time to recognise the extent of unpaid labour, especially that of women, on which rural water supply depends? And should we recognise the time used to travel to a place of open defecation or also the waiting time for shared sanitation?

In any case, given the magnitude of the challenge, governments should mobilise additional funding for the WASH sector and coordinate efforts at all levels to ensure cost-effectiveness and efficiency, particularly in resource-constrained environments. Developing WASH plans at sub-national level could be a good way to strengthening governance and coordination, and maximise cost-effectiveness.

What about serving those that cannot afford to pay? Those currently left behind include communities located in rural and remote areas who are often the poorest and currently rely on Self-supply. For those who cannot afford to pay and to address the issue of leaving no-one behind, various areas can be investigated:

- Defining and measuring users’ affordability

- Considering low-cost technology options such as Self-supply but only if accompanied by long-term support from local and national government (including through regulation)

- Making sure the solutions are acceptable and accessible for all – taking into account gender, disability, and cultural preferences

This e-discussion has been useful at clarifying knowns and unknowns related to costing and financing services. Even though the issue of affordability has been touched on, many questions remain unanswered.

We think this discussion should continue and here are a few questions, which we still have in mind, but you might have many more:

- Who are populations left behind in different contexts (including the marginalised and discriminated against) and how can we define and identify them?

- What are the ongoing costs of reaching everyone (including the aspects listed above)?

- If users are those paying the majority of WASH supply costs, how do we deal with those who cannot afford to pay?

- What mechanisms can be introduced to set tariffs appropriately, whilst also covering the costs of long-term service provision?

- What are the examples of supported Self-supply that have been successful?

- What are the specific roles of local government in ensuring no-one is left behind?

Continue the discussion with us and post your answers below or sent your contribution to the RWSN e-discussion group.

Photo credits (top to bottom): Dominic Chavez/World Bank; Alan Piazza / World Bank; Arne Hoel / World Bank; Gerardo Pesantez / World Bank