Il s’agit du dernier d’une série de quatre blogs intitulée “Le forage professionnel de puits d’eau: Apprendre de l’Ouganda” de Elisabeth Liddle et d’un webinaire en 2019 sur le forage de puits professionnel. Cette série s’appuie sur les recherches menées en Ouganda par Liddle et Fenner (2018). Nous vous invitons à nous faire part de vos commentaires en réponse à ce blog ci-dessous.

Si l’accès à des sources d’eau améliorées a été amélioré de manière progressive dans l’ensemble de l’Afrique subsaharienne rurale, plusieurs études ont soulevé des problèmes concernant la capacité de ces sources à fournir des quantités d’eau sûres et adéquates à long terme (Foster et al., 2018 ; Kebede et al., 2017 ; Owor et al., 2017 ; Adank et al., 2014).

Le secteur se focalise sur l’exploitation et l’entretien après la construction, mais également de plus en plus sur la qualité de la mise en œuvre afin de prévenir la défaillance des points d’eau dans l’avenir. (UNICEF/Skat, 2016, Bonsor et al., 2015; Anscombe, 2011; Sloots, 2010).

La Fondation Skat et l’UNICEF sont des acteurs clés dans ce domaine, plaidant conjointement en faveur d’une professionnalisation accrue du forage en Afrique subsaharienne. Ils ont récemment publié une note d’orientation sur le professionnalisation en matière de forage (UNICEF/Skat, 2016), soulignant six domaines clés qui doivent être abordés pour améliorer la qualité du travail d’exécution (voir Figure 1).

Dans ce blog, je me concentre sur l’aspect “cadres institutionnels ” de la Figure 1, avec une attention particulière sur la manière dont l’Ouganda a cherché à améliorer la réglementation du secteur privé ces dernières années en introduisant des systèmes de permis pour les entrepreneurs et les consultants en forage.

Fig. 1: Six domaines d’engagement pour l’exploitation professionnelle des eaux souterraines (Skat/ UNICEF, 2018)

Des recherches récentes en Ouganda (Liddle et Fenner, 2018) ont montré que les permis d’entrepreneur de forage ont grandement facilité le processus de passation de marché au sein des organismes d’exécution de travaux en Ouganda, la liste des permis d’entrepreneur de forage étant généralement le premier point de contact pendant l’évaluation des offres.

Ces dernières années, le Ministère de l’Eau et de l’Environnement a reconnu le besoin essentiel d’étendre ce système de permis aux consultants/hydrogéologues, étant donné la prolifération des “consultants à mallette” dans le pays (ceux qui n’ont aucune formation formelle en géologie ou en hydrogéologie). La question des consultants en mallettes est abordée dans le premier blog de cette série. Les consultants en mallettes soumissionnaient pour les travaux d’implantation et de supervision, mais les équipes d’évaluation au sein des organismes d’exécution n’avaient aucun moyen d’identifier ceux qui étaient réellement qualifiés pour ces travaux et ceux dont les documents d’appel d’offres (par exemple, expérience professionnelle, diplômes, etc.) étaient des faux. Le travail de qualité médiocre s’est ensuite poursuivi car les “consultants à mallette” remportaient de plus en plus de contrats.

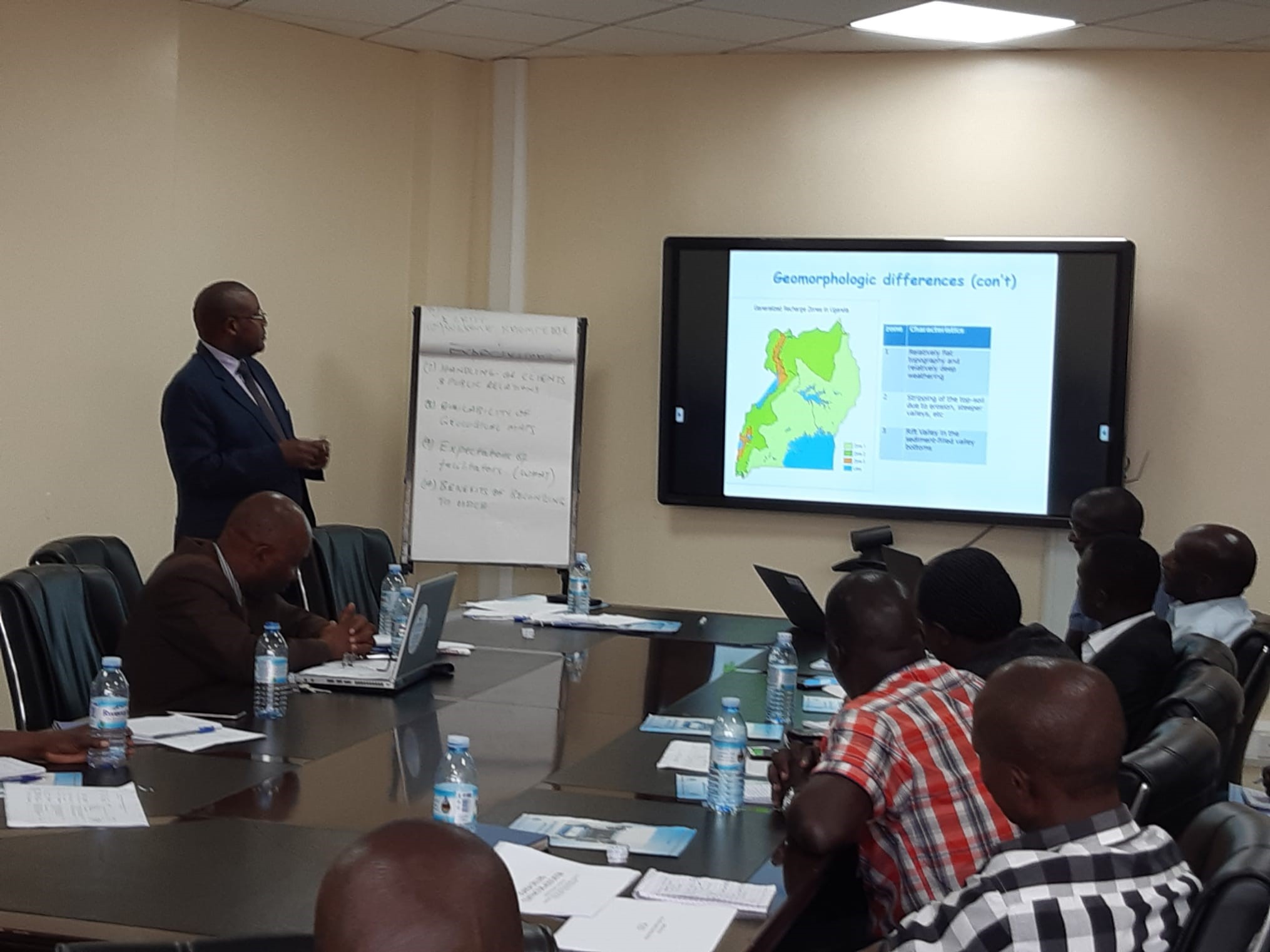

Pour résoudre ce problème et fournir des conseils aux équipes d’évaluation, le Ministère de l’Eau et de l’Environnement a entamé le processus de délivrance de permis d’hydrogéologue/consultant en 2016 (Tindimugaya, 2016). Les consultants peuvent demander un permis individuel d’hydrogéologue ou un permis d’entreprise en lien avec les eaux souterraines. Pour qu’une personne obtienne un permis, elle doit soumettre ses documents universitaires, son CV et un aperçu de son expérience professionnelle. La personne doit posséder des qualifications spécifiques en hydrogéologie (cours de courte durée, diplôme ou licence) ; des études en géologie seulement sont insuffisantes. Les locaux et l’équipement sont ensuite évalués, et une évaluation pratique ainsi qu’un entretien sont menées. Pour qu’une entreprise obtienne un permis, le directeur doit avoir un permis individuel. L’entreprise doit ensuite fournir les détails relatifs à l’inscription de son entreprise, une liste de son personnel et de leurs CV, ainsi que les détails de ses travaux antérieurs. A compter de juillet 2018, 65 personnes et 15 entreprises avaient reçu des permis. Comme pour les permis d’entrepreneur de forage, les permis des consultants sont renouvelés chaque année et des listes de consultants autorisés mises à jour sont publiées dans les journaux nationaux et en ligne chaque année en juillet.

Si ces systèmes d’octroi de permis ont grandement aidé les organismes d’exécution ougandais, des systèmes d’octroi de permis similaires, en particulier pour les consultants, semblent être rares dans le reste de l’Afrique subsaharienne. Selon Danert et Theis (2018), sur les 14 pays d’Afrique subsaharienne énumérés dans le rapport, seulement trois avaient mis en place des systèmes de permis pour les consultants, tandis que dix avaient mis en place des systèmes de permis pour les entreprises de forage. Il est maintenant essentiel que d’autres gouvernements d’Afrique subsaharienne suivent l’exemple de l’Ouganda et commencent à réglementer le secteur privé, en particulier les consultants, étant donné le rôle essentiel qu’ils jouent dans la qualité du travail d’exécution, l’implantation et la supervision des forages (UNICEF/Skat, 2016 ; Anscombe, 2011 ; Danert et al., 2010).

Qu’en pensez-vous?

Alors, qu’en pensez-vous? Avez-vous de l’expérience dans la sélection de professionnels qualifiés et expérimentés dans le domaine de l’eau souterraine ? Pensez-vous que l’octroi de permis aux professionnels est la voie à suivre dans votre contexte ? Y a-t-il des efforts pour mieux réglementer le secteur privé du forage dans votre pays ? Vous pouvez répondre ci-dessous en postant un commentaire, ou vous pouvez participer au webinaire en direct le 14 mai (inscriptions ici)

Références

Adank, M., Kumasi, T.C., Chimbar, T.L., Atengdem, J., Agbemor, B.D., Dickinson, N., and Abbey, E. (2014). The state of handpump water services in Ghana: Findings from three districts, 37th WEDC International Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014.

Anscombe, J.R. (2011). Quality assurance of UNICEF drilling programmes for boreholes in Malawi. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Agriculture Irrigation and Water Development, Government of Malawi.

Bonsor, H.C., Oates, N., Chilton, P.J., Carter, R.C., Casey, V., MacDonald, A.M., Etti, B., Nekesa, J., Musinguzi, F., Okubal, P., Alupo, G., Calow, R., Wilson, P., Tumuntungire, M., and Bennie, M. (2015). A Hidden Crisis: Strengthening the evidence base on the current failure of rural groundwater supplies, 38th WEDC International Conference, Loughborough University, UK, 2014.

Danert, K., Armstrong, T., Adekile, D., Duffau, B., Ouedraogo, I., and Kwei, C. (2010). Code of practice for cost effective boreholes. St Gallen, Switzerland: RWSN.

Danert, K. and Theis, S. (2018). Professional management of water well drilling projects and programmes, online course 2018, report for course participants, UNICEF-Skat Foundation Collaboration 2017-2019. St Gallen, Switzerland: Skat.

Danert, K., Carter, R.C., Rwamwanja, R., Ssebalu, J., Carr, G., and Kane, D. (2003). The private sector and water and sanitation services in Uganda: Understanding the context and developing support strategies. Journal of International Development, 15, 1099-1114.

Foster, T., Willetts, J., Lane, M. Thomson, P. Katuva, J., and Hope, R. (2018). Risk factors associated with rural water supply failure: A 30-year retrospective study of handpumps on the south coast of Kenya. Science of the Total Environment,, 626, 156-164.

Kebede, S., MacDonald, A.M., Bonsor, H.C, Dessie, N., Yehualaeshet, T., Wolde, G., Wilson, P., Whaley, L., and Lark, R.M. (2017). UPGro Hidden Crisis Research Consortium: unravelling past failures for future success in Rural Water Supply. Survey 1 Results, Country Report Ethiopia. Nottingham, UK: BGS (OR/17/024).

Liddle, E.S. and Fenner, R.A. (2018). Review of handpump-borehole implementation in Uganda. Nottingham, UK: BGS (OR/18/002).

Owor, M., MacDonald, A.M., Bonsor, H.C., Okullo, J., Katusiime, F., Alupo, G., Berochan, G., Tumusiime, C., Lapworth, D., Whaley, L., and Lark, R.M. (2017). UPGro Hidden Crisis Research Consortium. Survey 1 Country Report, Uganda. Nottingham, UK: BGS (OR/17/029).

Sloots, R. (2010). Assessment of groundwater investigations and borehole drilling capacity in Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Water and Environment, Government of Uganda, and UNICEF.

Tindimugaya, C. (2016). Registration of groundwater consultants in Uganda: rationale and status. RWSN Forum, 2016, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire.

UNICEF/Skat (2016). Professional water well drilling: A UNICEF guidance note. St Gallen, Switzerland: Skat and UNICEF.

Remerciements

Ce travail fait partie du projet Hidden Crisis du programme de recherche UPGro – cofinancé par le NERC, le DFID et l’ESRC.

Le travail de terrain entrepris pour ce rapport fait partie de la recherche doctorale des auteurs à l’Université de Cambridge, sous la supervision du Professeur Richard Fenner. Ce travail sur le terrain a été financé par le Ryoichi Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship Fund et UPGro : Hidden Crisis.

Merci à ceux d’entre vous de l’Université de Makerere et de WaterAid Ouganda qui m’ont apporté un soutien logistique, y compris sur le terrain, pendant que je menais les entretiens pour ce rapport (en particulier le Dr Michael Owor, Felece Katusiime et Joseph Okullo de l’Université Makerere et Gloria Berochan de WaterAid Uganda). Merci également à tous les répondants d’avoir été enthousiastes et disposés à participer à cette recherche.

Photo: E.S. Liddle