There is a multibillion-dollar finance gap slowing progress towards universal drinking water services. Focusing on how governments are investing to address this gap, a new open access research article examines the different elements that contribute to this gap, and argues that the funds needed for operations & maintenance (O&M) of services should be considered differently from the funds needed for infrastructure. With the functionality and sustainability issues the sector faces, these differences are worth paying attention to.

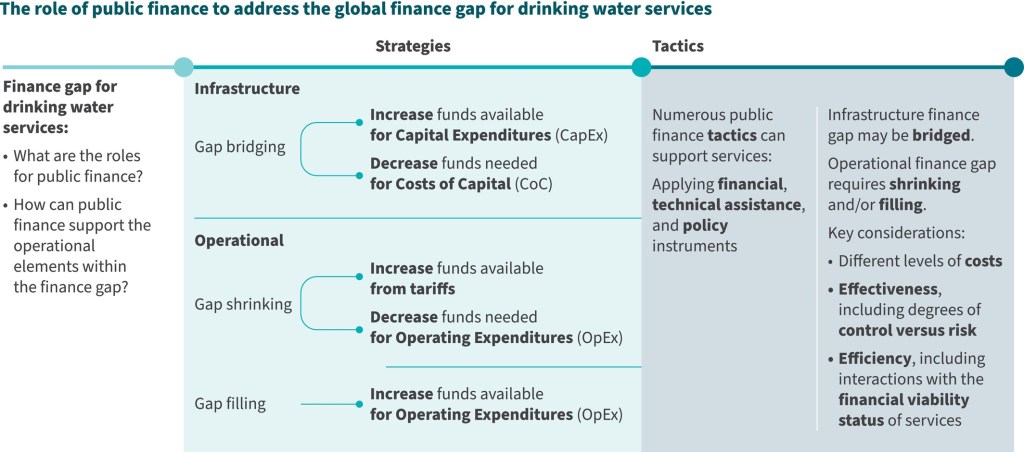

This research suggests a framework of five strategies for bridging, shrinking, and filling the finance gap for drinking water services, based on how the funds available from tariffs, taxes, and transfers compare to the life-cycle costs of services.

Do we need a new framework?

Maybe, yes! Approaches for targeting gaps in infrastructure finance have been well studied, with many frameworks already available to guide actions and suggest new funding sources and mechanisms. However, the parts of the finance gap related to operational needs has been less analysed, even though there is an increasing need for operational finance.

The water sector continues to struggle with the financial sustainability of drinking water services. Most repayable finance sources are not suitable for operational costs, and so it falls to governments and service providers to see how to balance ongoing costs and revenues. This framework shows that, after construction, there are fairly limited options: increase tariffs, cut costs, and/or set up subsidies.

How can the operational finance gap be addressed, to keep water services flowing?

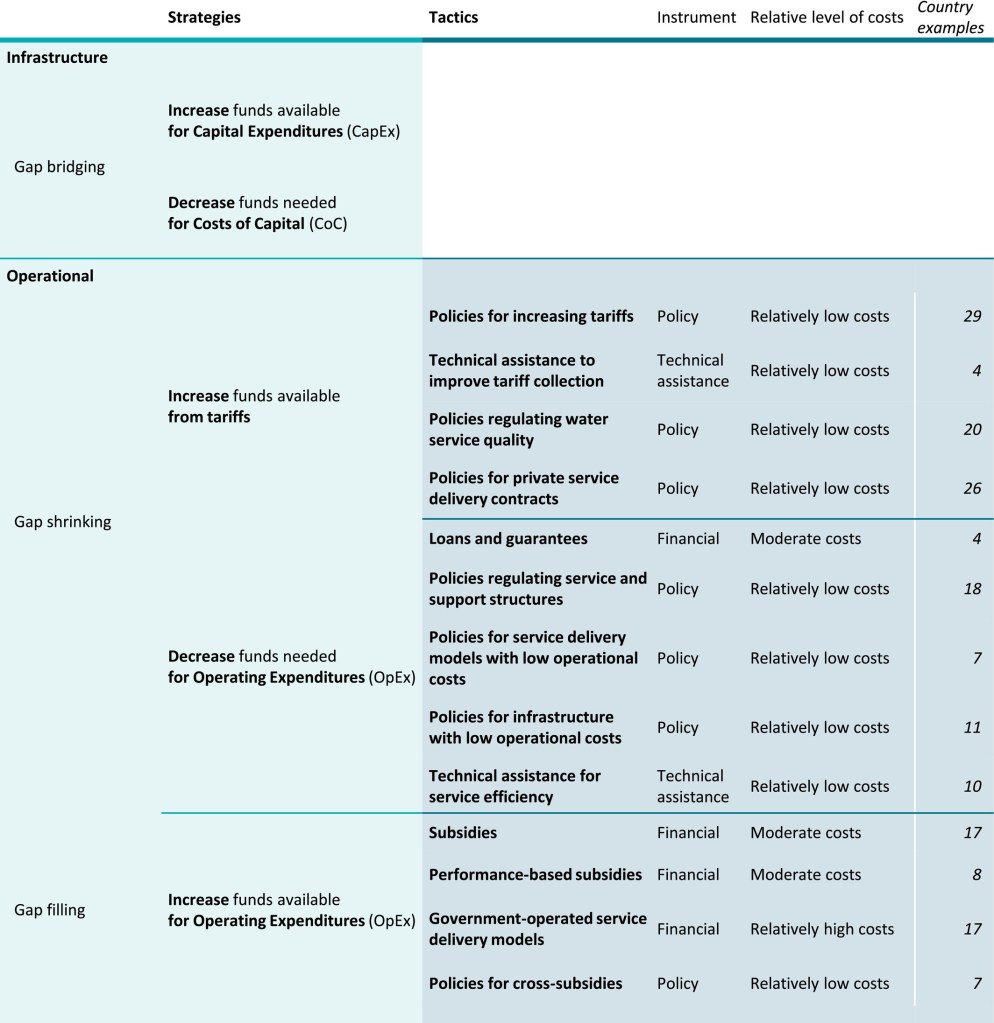

This research studied 213 examples of government investments for drinking water services, from 68 countries, to see how public finance is being used to address the operational finance gap. It found 13 tactics being used by governments from around the world, using financial, technical assistance, and/or policies, to:

- increase funds available from tariffs, and/or

- decrease funds needed for operations & maintenance, and/or

- increase funds available for operations & maintenance through subsidies.

These tactics, and their investment requirements, are presented here:

This framework could help to better understand and compare tactics for addressing the finance gap for drinking water services. To read more about this study, you can access the full article here: The Role of Public Finance to Address the Global Finance Gap for Drinking Water Services.

What do you think?

- Which tactics are being applied in your areas, by governments, or by other sector actors? Which are not?

- Are the tactics being used achieving what is needed, supporting services for more people, and services which are more financially sustainable?

- Are there other tactics being used that are not captured here?

About the author: Kristina Nilsson is a governance and development professional with over a decade of experience working on water and sanitation service delivery in Africa and Asia. She is currently a PhD student at the University of Oxford, researching public finance support for rural drinking water services.