Featured photo: Ghana, Lucy Parker

Article by Cincotta K. & Nhlema M.

Abstract

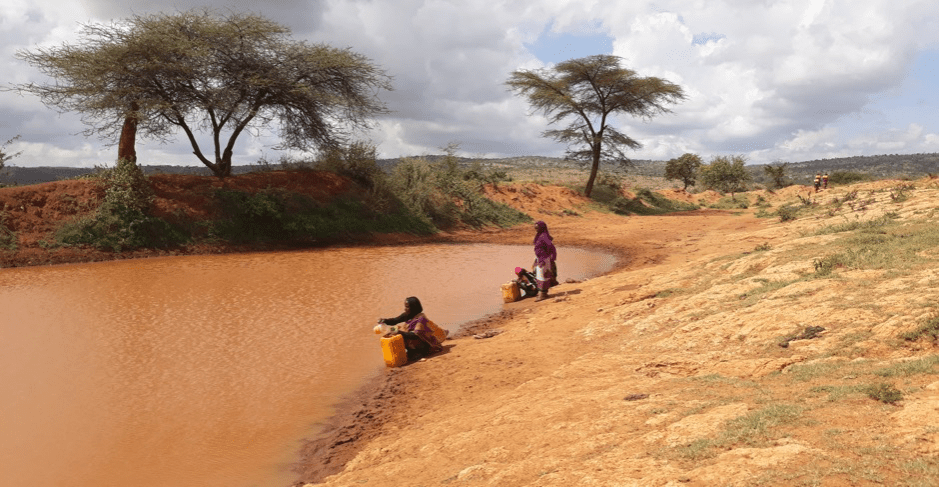

Rural water supply systems in low-income settings, particularly in last-mile communities, face chronic sustainability challenges. Financing predictable operation and maintenance (OPEX) remains a persistent gap, with one in four water points in sub-Saharan Africa being non-functional at any given time. While community-based management has been the dominant model for post-construction maintenance, it is increasingly recognized as insufficient, relying on underfunded household tariffs, volunteer committees, and limited technical support. Emerging solutions like results-based financing and professionalized maintenance contracts have shown promise with some securing government financing. This paper proposes district-level maintenance endowment funds, a mechanism where invested capital generates predictable income, as another option for financing rural water maintenance. These funds would support targeted subsidies, results-based contracting, and accountable, locally governed service delivery aligned with decentralization frameworks. This proposed model is agnostic to the specific management model, whether community-based, professionalized, or hybrid. The focus is on creating a predictable, long-term financing mechanism, particularly for so‑called ‘last-mile’ rural communities: small, dispersed villages, often with fewer than 1,000 people, that are typically excluded from piped water systems due to high per-capita service costs.

Two key arguments frame this proposal: (1) while endowment funds may be initially capitalized by international donors or organizations, over time they reduce dependency on short-term donor cycles by creating a predictable, locally managed revenue stream, and (2) Piloting endowments at the district government level strikes the right balance between being close enough to last-mile communities, accountable to them, and large enough to achieve economies of scale that will ensure financial viability for service provider payments.

THE PROBLEM: Persistent Non-Functionality and Unrealistic Expectations

Across sub-Saharan Africa, one in four rural water systems are non-functional at any given time. These failures are not anomalies, but they reflect a systemic global challenge: the absence of a reliable model for rural water service delivery beyond construction. For decades, community-based management (CBM) has been the dominant approach. It assumes that because communities value water, they will voluntarily manage infrastructure. But the viability of CBM is increasingly being questioned. Tariffs based on affordability rarely cover full maintenance costs, especially in small, dispersed communities, with variable incomes, that are often not prioritized for piped systems. Trained committee members often leave, and access to spare parts or technical support is limited. Volunteer fatigue, lack of retraining, and systemic underinvestment compound the problem.

The expectation that people living in the poorest rural villages must fully fund and manage the long-term maintenance of their own water systems does not align with how water systems are managed anywhere else in the world. In high-income countries, water infrastructure is maintained by trained professionals and supported by stable funding streams, often not limited to water user fees, but supplemented by public financing mechanisms such as property taxes and municipal budgets. The same should hold true, if not more so, in low-resource rural settings. A more realistic, equitable approach is therefore urgently needed.

TRIED AND TESTED SOLUTIONS: Results-Based Financing (RBF) – When Performance Meets Poverty

New RBF models are emerging. Uptime, as an example, is a partnership supporting professionalized rural water service providers that pays providers based on verified uptime. This shifts incentives from reactive repairs to preventive maintenance. Between 2020 and 2022, Uptime supported services for 1.5 million people in seven countries. Governments in countries such as Kenya, Bangladesh, and Zambia are now beginning to adopt performance-based financing approaches like this into their own public financing systems. This has been inspired in part by the evidence generated through philanthropic pilots. Yet, a central limitation remains: these models have demonstrated viability primarily in communities large enough or more “well-off” to generate economies of scale. This makes them financially attractive to service providers, but systematically excludes smaller, remote last-mile communities that are seen as less “bankable”. This is not a critique of performance-based models like Uptime, they are delivering results and proving their value. But it does highlight the need to pilot complementary result-based financing mechanisms that can address the unique realities of last-mile communities. Expecting the world’s poorest to fully finance their own essential services is neither equitable nor realistic. What’s needed is smart, targeted financing, including well-placed subsidies, that reflects the diversity of community capacity and directs public investment where it’s needed most. This is especially critical for last‑mile communities, i.e. remote, low‑density villages where user fees alone can never sustainably cover operating expenses.

This frame of thought, of differential and context-specific financing solutions, borrows from Dorward et al.: “Hanging In, Stepping Up, and Stepping Out.” Most rural households are “Hanging In,” unable to pay without full subsidy. Others can co-finance with support (“Stepping Up”), or engage with market models (“Stepping Out”). This model enables differentiated financing that aligns with real-world capacity. Targeted subsidies are not about dependence; they free up cash for productive use while ensuring reliable services. Importantly, we differentiate between water as a service that must be reliably provided for health and dignity, and water as a productive resource used to generate income. The proposed endowment-backed financing model speaks to the former, guaranteeing essential domestic supply. Other financing tools may be more appropriate for supporting productive uses of water in agriculture or enterprise.

RBF models have proven we know how to make maintenance work. The challenge now is to pilot solutions, such as endowment funds, that can sustainably support these communities where market-based approaches do not reach, thereby ensuring universal access to all.

THE PROPOSAL: District-Level Maintenance Endowment Funds

To close the financing gap, we propose district-managed endowment funds dedicated to rural water maintenance. These funds would invest capital to generate steady income for maintenance costs, insulating service delivery from budget shocks and donor cycles. They would:

- Provide predictable financing by requiring implementing agencies to allocate a fixed amount, e.g. 10-20% of infrastructure costs, into the fund.

- Enable targeted subsidies using the Hanging In/Stepping Out framework.

- Support results-based contracting for professional maintenance providers.

- Align with decentralization by placing fund management at the district level, while national governments serve as regulators.

This model borrows from urban utility principles where professional service delivery is underpinned by predictable financing and adapts them to rural realities. It does not assume full cost-recovery from users, nor does it treat water as a commodity for profit. Instead, it creates a stable platform for targeted subsidies and professional maintenance services in communities where user fees alone are structurally insufficient.

Continue reading “Financing Maintenance in Last-Mile Contexts: Endowment Funds for Rural Water Sustainability”