This is the second in a series of four blogs entitled Professional Borehole Drilling: Learning from Uganda written by Elisabeth Liddle, and a RWSN webinar in 2019 about professional borehole drilling. It draws on research in Uganda by Liddle and Fenner (2018). We welcome your thoughts in reply to this blog below. [Note: The original blog was revised on 03 April 2019 to correct an inaccurate representation of the situation].

While access to improved water sources has steadily increased across rural sub-Saharan Africa, several studies have raised concerns over the extent to which these sources are able to provide safe and adequate quantities of water over the long term (Foster et al., 2018; Kebede et al., 2017; Owor et al., 2017; Adank et al., 2014). Borehole design and siting are essential to ensure that the subsequent water point will continue to provide safe and adequate quantities of water. Access to detailed and accurate groundwater information can greatly aid siting and borehole design (UNICEF/Skat, 2016; Carter et al., 2014).

Skat Foundation and UNICEF have been key advocates for increasing access to detailed groundwater data including the recent guidance note which pointed out that ‘groundwater information’ is essential when seeking to improve the quality of borehole implementation in low- and middle-income countries (see Figure 1; UNICEF/Skat, 2016). In this blog I provide some insights into the ways in which Uganda has sought to increase access to groundwater data is recent years.

Fig. 1: Six areas of engagement for increasing drilling professionalism (Skat/UNICEF, 2016).

Groundwater resource mapping in Uganda

Significant steps have been taken in recent years to increase access to detailed groundwater data in Uganda. Much of this began in 2000 when the Directorate of Water Resources and Management (DWRM) within the Ministry of Water and the Environment (MWE) began a nationwide groundwater mapping project. Using data sourced from the borehole completion reports that drilling contractors are required to submit every quarter, DWRM has developed are series of maps for each district. These include:

- Water source location map, underlain by a geology map.

- Recommended water source technology map (technology recommendation is based on main water strike depth and yield information).

- Hydrogeological condition map – includes 4 sub-maps:

- Groundwater quality map: highlights areas where water quality is expected to be problematic.

- Groundwater potential – Drilling success rate map: combines expected yield success rate[5] coupled with expected water quality conditions.

Tindimugaya (2004) explains these maps in greater detail, along with the ways in which such maps can help the implementation process. An example of these maps for Kibaale district is available on the MWE’s website.

This mapping work is ongoing, however, by May 2017 DWRM had mapped 85% of Uganda’s districts. The magnitude of these maps and the level of detail they capture is remarkable. These maps have become a great asset for district local governments, non-governmental organisations, and others responsible for water point siting and construction.

Ongoing challenges

While Uganda has made remarkable progress in recent years with their groundwater mapping efforts, there have been several challenges along the way (Liddle and Fenner, 2018), mostly related to data accuracy. When interviewing those in Uganda for this research, there were reports that in some (but not all) cases, inaccurate data is submitted. When looking at why inaccurate data is sometimes submitted, two key issues were noted:

- There often isn’t a qualified consultant on site full-time for drilling supervision. While it is the drilling contractor’s responsibility to have a member of staff recording the drilling log, an independent supervisor should also keep a log and check the driller’s log for accuracy before this is submitted to DWRM. Without full-time supervision, however, this cannot happen. Furthermore, even with full-time supervision, if the supervisor is not a hydrogeologist, it is unlikely that they will be keeping accurate and detailed logs.

- The lump sum no-water-no-pay payment terms via which Ugandan drillers are often paid (see blog “Turnkey contracts for borehole siting and drilling”). When these contract terms are used, to be paid, drillers need to prove that they have drilled a successful borehole; as a result, there were reports of drillers exaggerating a given borehole’s yield in order to be paid. Skewing data in this way is concerning, as not only will these boreholes struggle to provide adequate quantities of water post-construction, but this high-yield data is then entered into the drilling log database and used to produce the hydrogeological maps. Increasing the quality of drilling supervision and ensuring data is not skewed in this way is essential if the accuracy of DWRM’s maps is to increase going forward.

Overall, Uganda has made remarkable progress over the past two decades in increasing the level of groundwater information available in-country. There are very few examples in the African continent comparable to what Uganda has achieved! As noted above, the resultant maps have become a great asset for district local governments, non-governmental organisations, and others responsible for water point siting and construction.

Increasing the accuracy of borehole completion reports is an essential next steps for Uganda. Furthermore, other countries should be aware of these challenges as they embark on their own mapping exercises and ensure necessary measures are in place to prevent these problems in their own contexts.

What do you think?

So what do you think? Do you have experiences of collecting and collating groundwater data, or using groundwater maps? Is this something that should be started in your country? You can respond below by posting in the reply below, or you can join the live webinar on the 14th of May (register here).

[1]‘Expected first water strike depth’ = the depth at which a driller is likely to first encounter groundwater. In most cases the driller will need to continue drilling past this point if the borehole is to be able to provide sufficient quantities of water for users.

[2] ‘Expected main water strike depth’ = the depth at which a driller is likely to find the main aquifer that will be able to provide sufficient quantities of water for users.

[3] Overburden refers to the unconsolidated material that overlays the bedrock. The ‘expected overburden thickness’ map highlights the expected depth of this unconsolidated material across Uganda.

[4] ‘Expected static water level’ = the expected groundwater depth without any pumping disturbance.

[5] ‘Yield success’ refers to a borehole being able to sustain a pumping rate of 500 litres/hour. If a borehole can sustain this pumping rate, it is considered successful in regards to yield.

References

Adank, M., Kumasi, T.C., Chimbar, T.L., Atengdem, J., Agbemor, B.D., Dickinson, N., and Abbey, E. (2014). The state of handpump water services in Ghana: Findings from three districts, 37th WEDC International Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014, Available from https://wedc-knowledge.lboro.ac.uk/resources/conference/37/Adank-1976.pdf

Carter, R., Chilton, J., Danert, K. & Olschewski, A. (2014) Siting of Drilled Water Wells – A Guide for Project Managers. RWSN Publication 2014-11 , RWSN , St Gallen, Switzerland, Available from http://www.rural-water-supply.net/en/resources/details/187

Foster, T., Willetts, J., Lane, M. Thomson, P. Katuva, J., and Hope, R. (2018). Risk factors associated with rural water supply failure: A 30-year retrospective study of handpumps on the south coast of Kenya. Science of the Total Environment,, 626, 156-164, Available from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969717337324

Kebede, S., MacDonald, A.M., Bonsor, H.C, Dessie, N., Yehualaeshet, T., Wolde, G., Wilson, P., Whaley, L., and Lark, R.M. (2017). UPGro Hidden Crisis Research Consortium: unravelling past failures for future success in Rural Water Supply. Survey 1 Results, Country Report Ethiopia. Nottingham, UK: BGS (OR/17/024), Available from https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/516998/

Liddle, E.S. and Fenner, R.A. (2018). Review of handpump-borehole implementation in Uganda. Nottingham, UK: BGS (OR/18/002), Available from https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/520591/

Owor, M., MacDonald, A.M., Bonsor, H.C., Okullo, J., Katusiime, F., Alupo, G., Berochan, G., Tumusiime, C., Lapworth, D., Whaley, L., and Lark, R.M. (2017). UPGro Hidden Crisis Research Consortium. Survey 1 Country Report, Uganda. Nottingham, UK: BGS (OR/17/029), Available from https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/518403/

Tindimugaya, C. (2004). Groundwater mapping and its implications for rural water supply coverage in Uganda. 30th WEDC International Conference, Vientiane, Lao PDR, 2004. Available from https://wedc-knowledge.lboro.ac.uk/resources/conference/30/Tindimugaya.pdf

UNICEF/Skat (2016). Professional water well drilling: A UNICEF guidance note. St Gallen, Switzerland: Skat and UNICEF. Available from http://www.rural-water-supply.net/en/resources/details/775

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the Hidden Crisis project within the UPGro research programme – co-funded by NERC, DFID, and ESRC.

The fieldwork undertaken for this report is part of the authors PhD research at the University of Cambridge, under the supervision of Professor Richard Fenner. This fieldwork was funded by the Ryoichi Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship Fund and UPGro: Hidden Crisis.

Thank you to those of you from Makerere University and WaterAid Uganda who provided logistical and field support while I was conducting the interviews for this report (especially Dr Michael Owor, Felece Katusiime, and Joseph Okullo from Makerere University and Gloria Berochan from WaterAid Uganda). Thank you also to all of the respondents for being eager and willing to participate in this research.

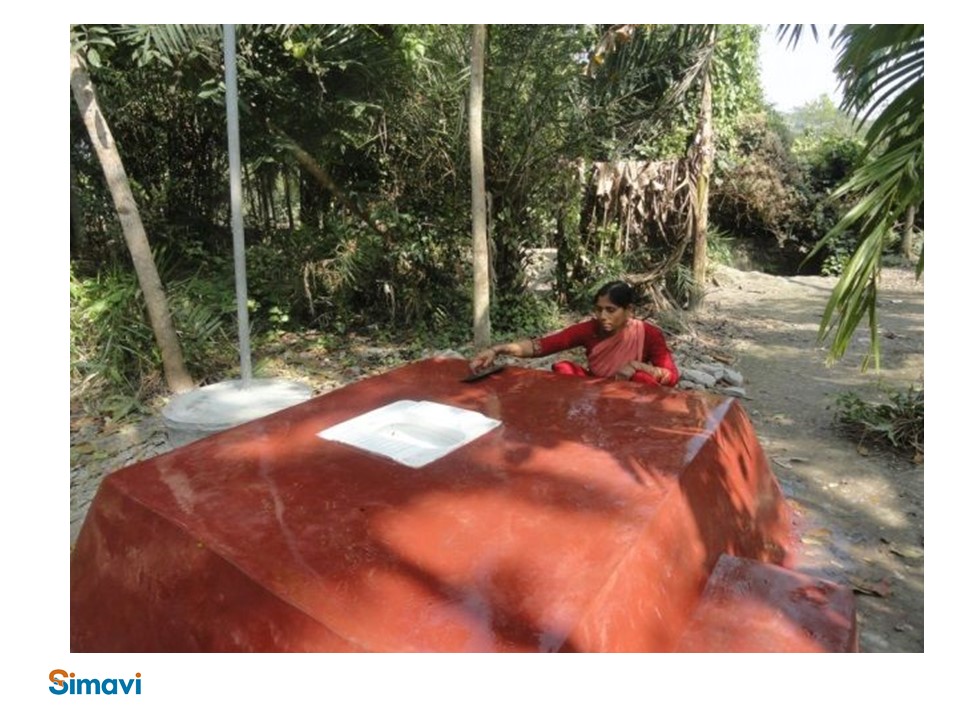

Photo: “Groundwater Supply Technology Options map on display in the Kayunga District Water Office” (Source: Elisabeth Liddle).